Wildlife and timber crime is a failure of business, industry, markets and investors. They demonstrate no understanding of the tremendous impacts of the poorly regulated procurement of endangered species for the global legal trade. Over the last 30 years, talk about sustainability has increased, bringing with it a growing pile of glossy sustainability reports. But we are further from sustainability in extracting biomass from nature than ever before. After decades of legal trade in endangered and exotic species there appears little commercial understanding of sustainable offtake levels. Begging the question, is it time for a moratorium on this trade until businesses, industries and shareholders provide the necessary investments to properly monitor and clean up supply chains?

While the conservation sector focuses on poaching and poverty alleviation, concentrating its efforts on the least powerful groups in the supply chain, the failures of powerful individuals, business and commercial institutions are missed, ignored or clinically sidestepped. These groups have driven up the desire for endangered and exotic species for profit. In the main exotic and endangered species are used to manufacture non-essential products for luxury consumers, fulfilling luxury lifestyle choices.

Most of the glossy sustainability reports, companies publish, highlight that supply chain transparency is critical to ensuring sustainability, yet very little has been invested into creating the necessary levels of traceability in the trade of endangered species. Without transparency and accountability in the whole supply chain, from the raw materials end to intermediate and final stage manufacturing, there can be no proof of sustainability.

In May 2019, a report published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), provided clear evidence that the legal trade was a key driver of population decline and the extinction crisis. The report concluded:

- Direct exploitation for trade is the most important driver of decline and extinction risk for marine species.

- Direct exploitation for trade is the second most important driver of decline and extinction risk for terrestrial and freshwater species.

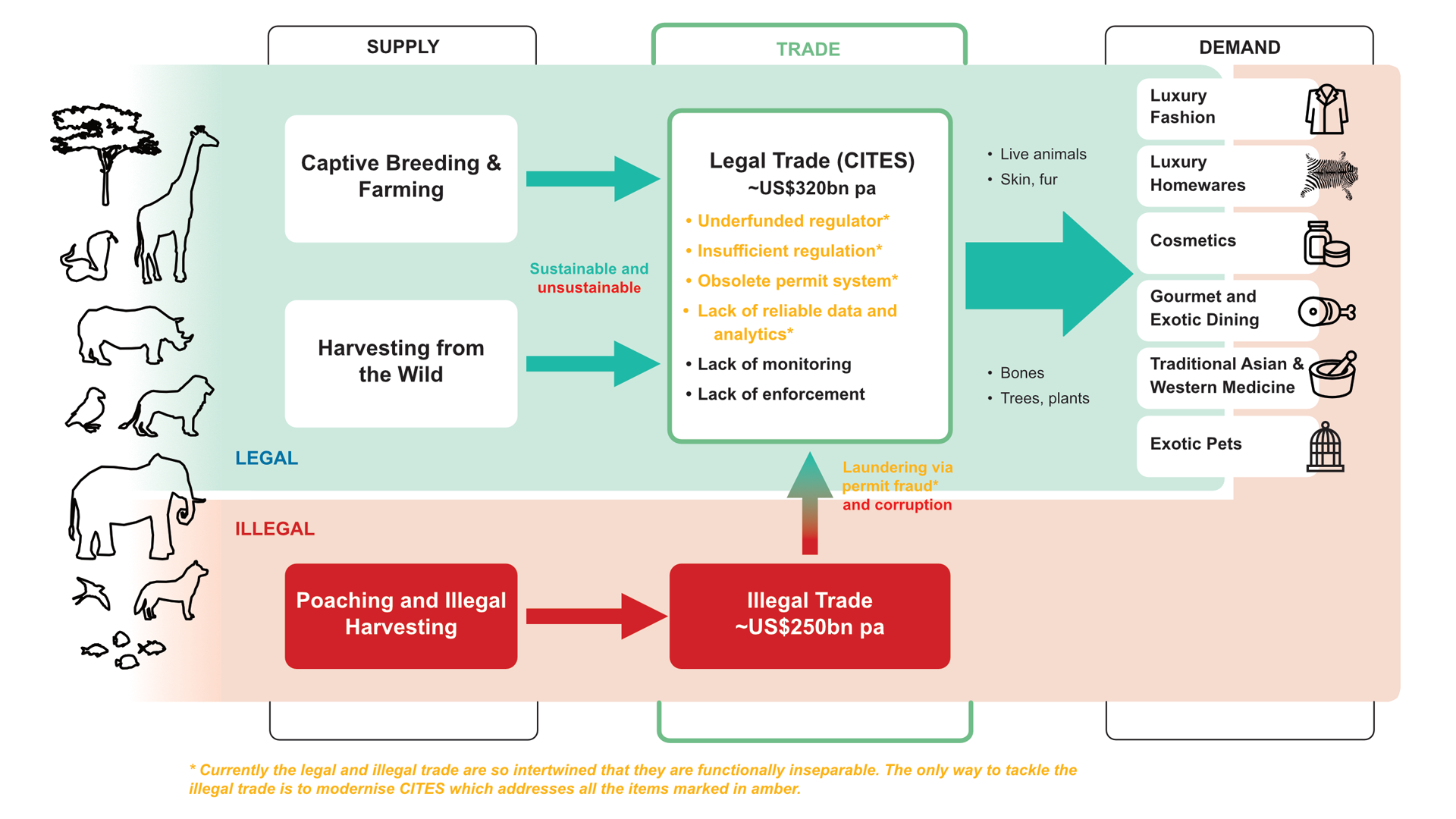

The regulator of the trade in endangered species, CITES, was launched in 1975, on the premise that creating a legal, global, sustainable trade was the strategy to protect species well into the future. This regulator has failed to achieve the very objective it was created for. CITES’ mechanism for keeping track of what is traded is so obsolete that the trade data it does collect are worse than useless and cannot be reconciled with customs information or the UN Comtrade database.

It is so easy to launder illegal products into the legal supply chain that in 2018 the WCO estimated the illegal trade in endangered species to be worth as much as US$258 billion annually. Given this is in the region of 80% of the value of the legal trade, this is again a clear indicator of regulatory failure. But this failure goes well beyond the CITES regulator.

This failure of appropriate supply chain management to keep out illegal items is enabling the industrial scale of wildlife and timber crime. This represents a failure of business, industry, markets and investors. It is time to demand that all the types of businesses, including personal luxury (clothing, accessories, jewellery, beauty, wellbeing etc), to high-end furniture, housewares, architects and property developers, luxury hospitality, fine dining and gourmet food and the exotic pet industry, involved in the trade in endangered and exotic species get serious about sustainability. All current evidence is they have their head in the sand and are focused on a business-as-usual approach.

For nearly 50 years, since CITES came into force, facilitating the legal trade in endangered species, business, industries, markets and investors have been protected. In this time, these stakeholder groups have never been made to prove that the trade they profit from is sustainable. They have never had to prove the effect on the wild cohort of the species they covet and exploit for trade. Quite the reverse, it is concerned conservation groups who must research the plight of a traded species, often for years or even decades. And, even when there seems to be irrefutable evidence of the vulnerability of a species, because of it being legally traded, it appears nearly impossible to stop it been commercialised.

In recent years, many more thousands of species have been added to the CITES appendices for trade restrictions. Of all the nearly 40,000 species listed for CITES trade restriction, only about 1,000 have the tightest of trade restrictions, supposedly banning them from all commercial trade. Yet the businesses who profit from this trade don’t have transparent supply chains. The markets who push for constant growth have shown no desire to put their foot on the brakes, and the investors who provide capital to help business grow have shown no interest in cleaning up the trade.

In theory, at least, even the World Trade Organisation’s rules say additional checks and regulations are permitted in cases where trade could negatively affect the environment. While the WTO primarily acts as a regulatory framework to facilitate international trade, it formally accepts that exceptions to free trade rules are very important in environment related issues.

In 2015, CITES and the WTO produced a joint statement agreeing that that the well-being of economies, habitats, and societies are inextricably linked. And what has been the impact on reducing the legal trade of endangered species as a result of these WTO agreements and assertions? No impact at all.

It is time to call it as it is, the extinction crisis is a result of business, industries, markets and investors, as is the industrial scale of wildlife crime. They have all profited from driving up the desire for products and services whose raw materials are the worlds most endangered species. They have made minimal investments in procurement management, governance and supply chain transparency.

What these stakeholders are pledging now, with their discussions of such things as a ‘Great Reset’, is nothing more than using a voluntary governance framework which has already been in place since 1997, and which hasn’t worked. There is no accountability here.

With all the talk of sustainability, there is no real transparency yet. And sustainability without transparency is just an ideology not a strategy.

True sustainability requires radical supply chain transparency. Given the current lack of commitment by business and investors, surely we are reaching a point where they must be challenged with, No Transparency – No Trade.

In the year ahead, Nature Needs More will build on our new campaign, No Transparency – No Trade (#NoTransparencyNoTrade)

We hope that you will join us in our push to business, industries and investors to deal with their failures, which have enabled over-exploitation, the extinction crisis and industrial scale wildlife crime. These stakeholders must be held accountable for their failures. It is time to dictate what is needed, radical transparency in the form of body cameras when harvesting, CCTV in all captive breeding and cultivation facilities, tagging of all shipments, real-time traceability, trade analytics and trade risk flags (including biosecurity risk flags). Business must resource independent regulators, such as CITES, via trade levies. And business must cover the cost of their own mistakes; if taxpayers are left to cover the costs of the mess they create, there is no incentive to improve business behaviours.

In the last 50 years, these stakeholder groups have shown little intrinsic motivation to evolve to protect the species that they profit from. They can’t now complain if the necessary changes are forced on them. Wildlife, and the natural world, doesn’t have the luxury of time.