In my past 4 blogs I have explored Australia’s involvement, both legal and illegal, in the global Exotic Pet Trade (EPT). The world’s desire for exotic pets is only growing and as previously highlighted, “the scale of trade for the EPT is enormous around the world. In the years 1996-2012 it is thought that 18.8 million CITES listed reptiles were imported into the EU – an astounding figure when you consider that 75% of reptiles are not listed on CITES. While the US alone is thought to import more than 11 million aquarium fish annually representing more than 2300 species.” Warwick et al suggest that potentially 13,000 species are traded in the global EPT.

Australia plays a hand in this trade, both knowingly and unwittingly. Be it the $350 million trade in fish and coral for the worldwide marine aquarium trade or the illegal export of birds and reptiles to feed the desire for consumption of that which is exotic. Australia’s many unique species are a hidden treasure trove in this regard.

This all comes with risks though and in my last blog, The Risky Business of Heavy Petting, I broadly categorised these as, 1. Animal Welfare, 2. Biosecurity/Invasive Species, 3. Public Health and 4. Biodiversity Loss. Having identified the risks how then do we mitigate these? What are some of the ideas for managing the trade of exotic pets? I will not profess to have an exhaustive summary but let’s look at some of the approaches that are being used or could be considered. I’ve broken these into six strategies – Technology, Transparency of Trade, Law Enforcement, Demand Reduction, Reverse Listing and Cost Recovery – and this article will look at the first three of these.

Technology

In Australia a recent article in the media covered a number of novel ideas being developed – Cutting edge technology is being deployed to stop the illegal trafficking of Australian wildlife. This looks at projects that are:

- Developing rapid DNA testing to identify exotic species including from transport containers once the animal has been removed.

- Building artificial intelligence (AI) systems to scan the internet to monitor wildlife trade and identify illicit trade

- Devising forensic tools that look to identify the origin of an individual by scanning it at the point of detection, as well poo analysis to determine if the individual’s diet reflects captive or natural origins.

In looking more specifically at the idea of radiocarbon dating/DNA testing I would here tie in my interest in rhino conservation. A 2018 enquiry looked into the legal, domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn in Australia. Lobbying for the enquiry resulted in one of the supportive federal MPs requesting information from the parliamentary library. Records show that between 2010 and 2016 there were 411 seizures of (suspected) ivory and 25 seizures of (suspected) rhino horn. The parliamentary library paperwork uses the word ‘suspected’ throughout the documentation and no evidence could be found, or was offered, that the first step in building a case to prosecute those carrying these confiscated items was undertaken, namely DNA testing and radiocarbon dating of the confiscated items.

Were any of the items, from 411 seizures of (suspected) ivory or 25 seizures of (suspected) rhino horn, tested? In speaking to individuals, at the time, who could administer such DNA testing and radiocarbon dating Nature Needs More were told that “We can test what is seized, but no government wants to pay for testing”. This lack of testing, effectively the first step in building a case for prosecution to occur, also explains the lack of convictions over the years.

Undoubtedly technology for testing has improved in the intervening years – it is quicker and probably cheaper. As the linked article states, “The 24-hour test was developed with the support of the federal government, which donated its stock of seized rhino horns for science.”. I’m interested though, what was the result? Did the test show that any of the horn came from killed rhinos? If so, had the details of the person the rhino horn was confiscated from been kept? If the horn was illegal, have these people now been charged? The penalties apply for the possession of specimens that have been illegally imported and range up to $210,000 for an individual ($1,050,000 for a body-corporate) and/or 10 years imprisonment.

So, while developing new technology is good, it must then be used in a way and on a scale that drives change, otherwise what’s the point? In fact, promoting its development and not ensuring it is progressed to the point of a useful role gives false hope. It’s also worth noting that while developing new technologies is newsworthy and hopefully worthwhile, we must ensure that existing technologies that could be easily upscaled in a cost-effective way should not be ignored. More on this in the Transparency section below.

As with all these sorts of strategies, cost, and who pays, will be a factor in the uptake of the technology, as without rolling these ideas out on sufficient scale they will remain of limited value. I will cover the issue of meeting the costs of these sorts of ideas in the next blog.

Transparency of Trade

Flowing on from technology let’s consider transparency of legal trade; for Australian species this falls mainly in the basket of our involvement in the Marine Ornamental Fish (MOF) trade. However, this is also relevant to offshore trade in native Australian species, remembering that in many cases this is not illegal.

In general, I would contend the transparency of trade is woefully inadequate. There is no universally adopted system that monitors trade in species traded in the EPT. In the USA, LEMIS (Law Enforcement Management Information System) is used to record the volume and the origin of wild animal and plant specimens imported for reasons of law enforcement. My sense is that the system is considered by many in the world to be the ‘gold standard’ to aspire to. But a paper published Feb 2024 in Conservation Letters titled, US wildlife trade data lack quality control necessary for accurate scientific interpretation and policy application by Bruce Weissgold (ex FWS trade) states, “Based on firsthand experiences with the creation and application of LEMIS data, this manuscript describes a variety of errors, biases, omissions, and an overall lack of data quality assurance. An independent audit of the LEMIS wildlife trade database and the service’s policies, procedures, and protocols for managing this system is needed. Additional recommendations are also offered to develop better management standards and bring greater resources for managing LEMIS…..The specialized user community of LEMIS import–export data—principally NGO and intergovernmental organizations and federal government agencies—are sometimes aware of the system’s shortcomings. However, they have engaged in virtually no efforts to improve and correct these data. As such, those groups, particularly NGOs which have regular contact with the US Congress’ appropriation processes, should assist USFWS in improving the management and administration of LEMIS to better ensure the accuracy of the data through the establishment of quality control measures and greater transparency measures and public access”.

In the case of the EU, their TRACES (Trade Control and Expert System) system is a good attempt to monitor trade. The European Commission’s website suggests that, “TRACES is the European Commission’s online platform for animal and plant health certification required for the importation of animals, animal products, food and feed of non-animal origin and plants into the European Union, and the intra-EU trade and EU exports of animals and certain animal products.”. However, we know that not all trade reporting is down to the level of species, and it is not a universal system that allows end to end traceability.

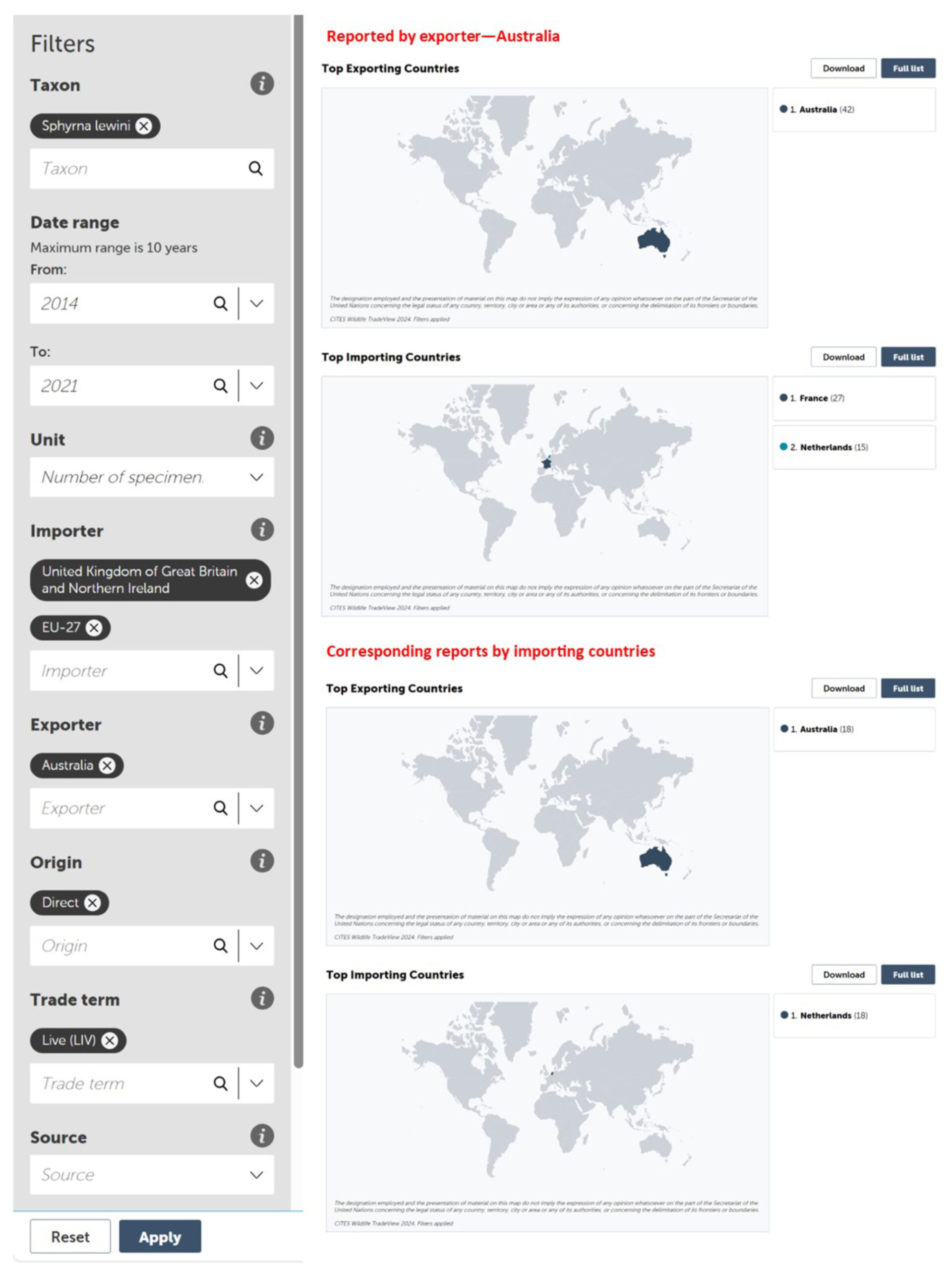

I was interested to see if the trade in a species monitored by both systems was comparable; the international trade in the Scalloped Hammerhead Shark is documented both by CITES and TRACES. In this case, I investigated the number of ‘live’ specimens exported by Australia to Europe between 2014 and 2021. Given the trade volume is very small, the expectation should be that these two systems, and the companies who use them, can dot their I’s and cross their T’s. But this is not the case – maybe it’s more a case of close their I’s and trade as they please!

Between 2014-2021 the TRACES system records 62 individuals imported to the Netherlands from Australia. Australian export data, obtained using the CITES Trade website, reports in the same period that Australia exported 42 specimens in total to Europe, of which 15 went to the Netherlands and 27 to France. In the corresponding trade data, the Netherlands reports importing 18 specimens from Australia, there are no trade records of imports by France.

How do we ever have any idea on what is being traded where and imagine the discrepancies for higher volume trade!

And, while continental Europe does have the TRACES system, there is no excuse for the countries in this wealthy region of the world to still be using the CITES 1970s paper permit system. As the example above clarifies, TRACES is not enough to ensure Europe’s trade supply chains are well managed or transparent. Only three of the EU-27 countries have modernized their CITES trade permit system – France, Belgium and the Czech Republic. The UK also still uses the 1970s paper permit system for trade.

In my view, the importance of CITES cannot be overlooked in this section on transparency. Nature Needs More has a strong belief that issues around biodiversity loss, illegal trade and biosecurity can only be meaningfully managed and addressed if accurate data can be sourced. This year’s UNODC 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝 𝐖𝐢𝐥𝐝𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞 𝐂𝐫𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐑𝐞𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭 highlighted that, of the seizures relating to illegal trade in 162 countries and territories during 2015 to 2021, over 80% of the species seized were listed under CITES. The CITES trade system by nature covers a large portion of the most threatened species in the world; and is and will continue to grow. In addition, it is the most universally adopted, legislatively embedded treaty that COULD provide useful data but for its permitting system that is not fit for purpose. In the case of the EPT trade from Australia, a global roll out of an electronic permitting system for CITES would allow real time data, end to end traceability and full trade transparency of listed species that we trade.

The reality is that trade transparency must be prioritized. The technology to largely solve the issue of transparency exists through off the shelf e-permitting systems already developed such as the ASYCUDA eCITES option. Australia should be leading the push to see e-permitting for CITES rolled out worldwide. Otherwise, in the case of CITES listed species plausible deniability remains the status quo, decision making is made on hunches not fact and claims of sustainability remain ideological rather than strategic.

As we approach the next round of the Convention on Biological Diversity, CBD CoP16 in October in Columbia, if business won’t commit to supply chain transparency for 40,000 of the most commercially lucrative species, listed under CITES what chance do the rest have, which have no regulation.

The CBD was set up to promote sustainable development and it states its 3 main objectives are:

- The conservation of biological diversity

- The sustainable use of the components of biological diversity

- The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources

Whatever is discussed in the leadup to the CBD CoP 16, from Nature Positive to Natural Capital and more, while there is no commitment to transparency there is no proof of sustainability or legality. The lack of proof on the sustainable use model is becoming evermore apparent, as multiple meta-analyses either find no proof, conclude proof is inconclusive and even show sustainable use has a negative effect.

The situation is so dire and we have such a limited time to mitigate the risk, is it time for the conversation to demand No Transparency – No Trade? The decades of the no-trade/pro-trade debate clarifies that pro-trade is the clear winner. As a result, it is up to the pro-trade proponents (business, investors, governments, IGOs, NGOs) to prove that all trade in wild species is both sustainable and legal. They haven’t done this in over 50 years with the methods they are wedded to.

The lack of transparency makes any claim of sustainability nigh on meaningless. When looking at biomass extraction in general then there is little evidence that big business is intrinsically motivated to change. They invest in the illusion of being good corporate citizens (with the likes of CSR, Nature Positive, Net Zero, ESG governance) and other phantom solutions. The fact that so little has been committed to the natural world for so long, is an indication that most people aren’t intrinsically motivated to change. Given this, the only option to enable trade to remain would be a global move to a Reverse Listing Model but I’ll come to that in my next blog.

Law Enforcement

There is undoubtedly scope for increasing the number of inspections and upskilling personnel involved at the frontline of border security. It is important to note here that for those countries that are parties to CITES there is NO compulsion to have a Law Enforcement Authority associated with this commitment. While it is mandatory to have a Management and Scientific Authority a commitment to the policing of the treaty is optional. In the case of 85 signatory countries this would seem to present the situation of a toothless tiger when it comes to enforcing the transgressions under CITES commitments.

Let’s then look at the issues of border protection. Nature Needs More had a number of conversations with customs officials during the investigation in to the domestic trade of elephant ivory and rhino horn. These suggested that training levels are low, interception of illegal wildlife trade is often by chance and in many cases driven by an individual’s own personal interest rather than a systematic approach to tackling the issue. This is a difficult field, there are potentially hundreds, if not thousands of species if we include marine species, that may be exported illegally.

As I identified in my article on the marine aquarium trade, in some cases very few people may have the skills to even identify things such as coral down to the species level. Improving customs processes and detection and expanding and supporting law enforcement investigations will need investment.

In the cases of illegal export that are detected in Australia, the next question is, are penalties adequate? Currently wildlife crime appears to be viewed as a low risk, high return venture as highlighted in the Fintel Alliance report – Stopping The Illegal Trafficking Of Australian Wildlife Financial Crime Guide October 2020, “There is significant financial motivation for criminals to illegally export Australian wildlife for the overseas exotic pet trade. Organised criminals are attracted to the Australian illegal wildlife trade by large profits and lower penalties compared to smuggling illicit substances.”

Considering the welfare issues I discussed in my last blog and risks to biodiversity loss, in addition to improving our detection and investigation of illegal wildlife crime I believe we should reappraise our penalties for those caught. It seems smart to shift the balance of risk/reward for this crime.

Setting aside for now that too few people in the conservation sector are lobbying for the legal trade system to be better regulated, to help decouple the legal and illegal trade, let’s focus on what happens in the illicit trade.

Increasingly there has been a push by key conservation people and organisations to improve the resources for policing and prosecuting the illegal wildlife trade. So, it came as some surprise and a real disappointment recently that the UK government cut back the Metropolitan Police’s wildlife crime unit. The decision to redeploy the unit’s detectives to local policing was described as “woefully wrong” by the animal welfare charity Naturewatch Foundation. What message does this send about the importance of wildlife crime. Certainly, in the case of the EPT, it once again pushes the risk reward equation to the benefit of the criminal. This I strongly suspect is cost driven and once again the importance of animals, biodiversity and the natural world is placed low on the importance scale. If cost is the driver, there is a solution – I will cover cost recovery options in my next blog.

So, three down and three to go. In my next blog I will look at the second half of the concepts that could be used to mitigate risks associated with the EPT. It’s not an easy problem to address but no action simply does not seem an option.

Every step taken is one step closer to a better outcome for the world’s wildlife. If we sit and wait for the perfect solution then in reality it seems likely that time may well beat us when considering the risks we are facing. Keep an eye out for my next blog very soon to wrap up these ideas.

To read my early blogs in the series on the Exotic Pet Trade, see the links below:

Petted To Death – Australia’s Little Known Contribution To The Extinction Crisis

Australia’s Exotic Pet Trade Is Both Surprising And Rising