If any profession should have the loudest voice on issues of animal welfare and species conservation, it’s the veterinary profession. We are the ones who in many cases take an oath to care for animals, who dedicate our lives to their wellbeing. But are we, as a profession, truly living up to this responsibility? Why are we not the loudest voice yelling from the roof tops on these issues?

As veterinarians, we are entrusted with the health of countless individual animals, but is this enough? The world’s wildlife populations are in crisis, ecosystems are being destroyed, and species are disappearing at an alarming rate. We have the knowledge, the science, and the compassion to do more, but are we speaking up?

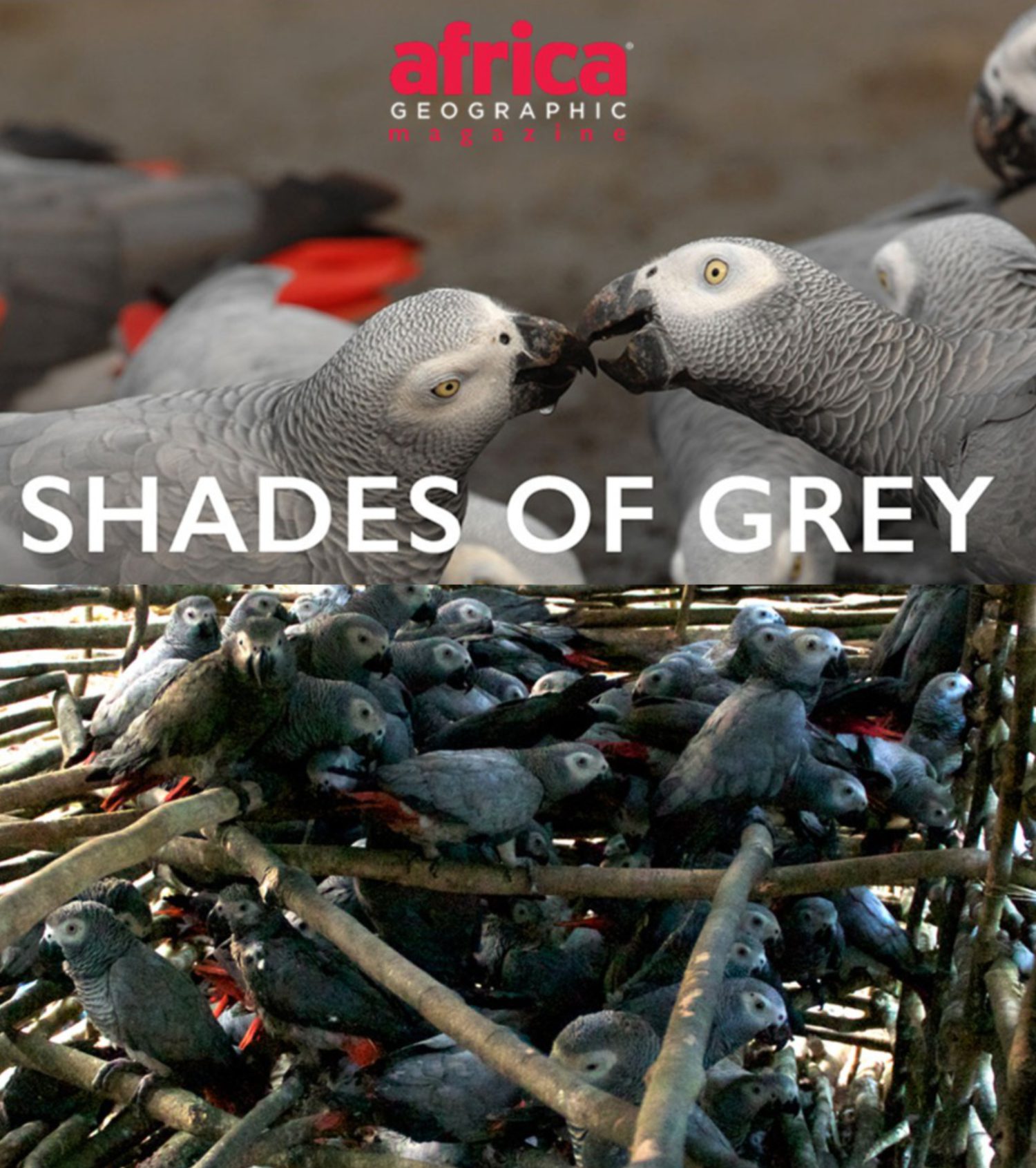

There have been ample exposés of the problem, such as the 2014 Africa Geographic article, The Journey From A Bustling Forrest To Solitary Life In Your Living Room, for Grey Parrots. Such investigations have exposed the problems not only for birds but also reptiles, mammals, fish and more.

I believe all in the veterinary profession should be looking beyond the animals in our personal care and advocating for the larger issues that threaten the very fabric of life on Earth. If as vets we did this, then maybe we would influence the welfare and wellbeing of thousands or even tens of thousands of individual animals more than the proportional handful of lucky ones that are presented to our clinics?

In this blog, I want to explore the veterinarian’s role in the broader context of animal welfare, biodiversity, and the environment. We’ll reflect on the oaths that guide our profession, examine the pressing issue of wildlife trade, and consider how veterinarians can embrace the principles of One Health to create and guide a more sustainable future.

When we enter the veterinary profession, in many jurisdictions we are asked to take an oath. In Australia this is variable by state. In the UK, this oath is focused on the care of the individual animals entrusted to our care:

“…my constant endeavour will be to ensure the health and welfare of animals committed to my care.”

This UK oath makes it clear that our primary responsibility is to the animals in front of us—those we treat, diagnose, and heal. But what about the animals we don’t see in our clinics—the ones whose lives are impacted by deforestation, climate change, the illegal wildlife trade or by the pet owners who simply can’t or won’t commit the funds for veterinary care?

What about the species whose survival is threatened by human activity, yet we may never treat them directly? As the profession entrusted to care for animals should we not be accepting a broader responsibility to be the advocates for all animal species and not just the lucky ones who are presented to our clinics?

The World Veterinary Association (WVA) offers a broader, more global perspective in its model oath:

“… to use my scientific knowledge, skill and training: To prevent, diagnose, treat and manage pain and disease in all animal species to the best of my ability….. help prevent the impact of zoonotic diseases and public health risks …. To advocate for the humane and sustainable management of terrestrial, aerial, and aquatic animals in their diverse ecosystems through stewardship to reduce environmental impacts. To contribute to animal, human, and environmental health ….. promoting health and welfare of humans and animals,”

This oath pushes us to think beyond our consult rooms and surgery theatres, urging us to use our expertise to protect species, ecosystems, and the planet as a whole. It calls on us to become advocates for the environment, to stand up for sustainability, and to tackle the root causes of animal suffering on a global scale.

The wording of this oath comes with a far greater level of responsibility and a higher expectation of the individual. I don’t think this means we should all be down tooling and moving into conservation jobs but I do think it means we should have a responsibility to be aware of the wider issues affecting all animals.

Shouldn’t we be advocating for all animals, not just those we see in our clinics? Should we be pushing for a more proactive role in protecting biodiversity and the ecosystems that support life? It’s time we asked ourselves whether our professional myopia is too narrow in scope—and whether it’s time for a new, broader commitment.

As veterinarians, we often focus on our immediate duties—diagnosing, treating, and preventing diseases in the animals in front of us. But should this be all we do? What about the larger systemic issues that affect animal welfare, conservation, and the environment?

There’s a growing disconnect between our responsibility to individual animals and the broader challenges affecting entire species and ecosystems. For example, should we continue recommending products derived from endangered species—like shark cartilage for arthritis treatments—when we know the impact this has on the environment? Should we be treating exotic pets in captivity, knowing that they often live in conditions that are far from their natural habitats?

I believe that at times, we hide behind our duty of care to the individual animal, avoiding the uncomfortable reality of how our actions may contribute to the bigger issues of wildlife trade, habitat destruction, and climate change. Yet, as veterinary professionals, I would contend that we have a moral and scientific obligation to consider the larger picture. We must ask ourselves: Are we ignoring the broader consequences of our actions to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths?

It’s time to look beyond the clinic. As animal lovers and professionals, we have the knowledge and the ethical responsibility to advocate for change on a global scale.

Last month the Australian Veterinary Association (AVA) ratified and posted on its website a new policy entitled – Exotic Pet Wildlife Trade. In the name of transparency I will declare I was one of the contributors to the development of this policy over a two-year period. This is the most extensive policy the AVA has ever developed in relation to the trade of wildlife and marks an opportunity for the Australian profession to become a leading voice in the area. The issue of wildlife trade involves so many areas that as a group of animal lovers we should all be interested in and maybe in the modern world “outraged” by. There are issues of welfare, biosecurity, zoonotic disease and ultimately the potential loss of species tied into this field. In retrospect I wonder, why to this point in time, is so little heard from a profession that has an inherent interest in all these areas?

The policy is relevant to three critical areas:

- Exotic Pets: The growing ethical dilemma of keeping non-domesticated species as pets.

- Wildlife Trade: The issues surrounding both legal and illegal wildlife trade and its impact on species survival.

- One Health: The recognition that human, animal, and environmental health are deeply interconnected.

The AVA policy defines an exotic pet as an animal, “considered unusual or uncommonly kept in a home and would in general be accepted to be a wild species rather than domesticated.” Broadly these animals are not adapted to a life in captivity, and it is generally accepted that meeting the 5 Domains of animal welfare are at best difficult. In the British Veterinary Association’s position paper on Non Traditional Companion Animals (NCTAs – Exotic Pets) they note that their, “2022 Voice of the Veterinary Profession survey found that over eight in ten vets (81%) were concerned that the welfare needs of NTCAs were not being met.” Concerningly, when this was narrowed down to the vets who actually treated NCTAs directly, “report that over half (58%) of the NTCAs they see do not have their five animal welfare needs met.”

Imagine if the vets working in small animal practice dealing with our much loved dogs and cats reported that more than half their patients were suffering poor welfare. As a profession, and even as a society, would we accept this as reasonable? I think the answer would be an emphatic NO!

Let’s be clear, in the case of non domesticated species – namely exotic pets/NTCAs – we are keeping these animals almost purely for our own satisfaction when in reality the very large bulk of these would likely live a better life in a natural environment.

The policy calls for stronger regulation of the exotic pet trade and Australia’s contribution to it. Additionally, it calls for a commitment to sustainable practices in wildlife trade. Australia has a strong stance on the trade of our native species through our EPBC Act (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). The Act, while not perfect and overdue to be revised, largely offers protection from trade for all our terrestrial and bird species. Is it time though, that this is extended further to cover species that sit on the coast line and deeper? We’ve drawn a line in the sand previously, but I would argue this should be extended under the waves. Is there really a need to supply our wild species from these domains to supply the exotic pet trade. From hermit crabs, to corals to marine fish species we continue to trade our natural world – a trade not without risk as I have previously covered in my blogs. This point is picked up in Point 1 of the new AVA policy and I hope may act as guiding point on future policy on this issue.

More broadly, by recognizing the ethical and environmental issues of the wildlife trade, the AVA is pushing the profession to lead the way in advocating for more humane and sustainable practices. The bulk of consumption of wildlife falls into the supply for seafood, fashion and traditional medicine. Australia is certainly involved in this but as veterinarians our points of enquiry should be the same using science and fact – is the trade transparent, are claims of sustainability valid, are we adequately addressing the impacts on the species involved. As a profession we must be cognitive that just because trade is legal, it doesn’t mean it is sustainable. This is picked up by Point 6 in the AVA policy – “The legal trade must be transparent and sustainable ……. Any legal trade where this has not been demonstrated is opposed.” LEGAL trade is the biggest threat to marine species and the second biggest to terrestrial and freshwater species according to the landmark 2019 IPBES report.

The concept of One Health—the idea that human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected—is becoming increasingly important. As veterinarians, we have a unique opportunity to promote a more holistic approach to health that considers the broader ecosystem in which we live.

Human existence and health, like it or not, is inextricably linked to the natural world. The publication, the Joint American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA)-Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA)- Federation of Veterinarians of Europe (FVE) statement on, “The Role Of Veterinarians In Advancing One Health —A Global Public Good, puts forward these groups position on the issue of One Health. It states that the professionals they represent should be “Protecting and advancing the health and welfare of all animals.” It goes further to suggest the profession should be contributing to, “Developing and implementing guidelines that govern the international trade of animals and animal products in order to not only protect animal health and welfare, but also human and ecosystem health”.

One Health recognizes that the health of animals, humans, and the environment cannot be separated. The rise of zoonotic diseases—diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans—has demonstrated this connection all too clearly. But this isn’t just about global pandemics. In the UK for example, 27% of children under the age of five hospitalised for salmonellosis were from homes with pet reptiles.

Veterinarian’s knowledge of their clients can certainly help inform behaviour change specialists to create well targeted demand reduction campaigns.

But One Health also extends to the broader impacts of environmental degradation on wildlife populations and the loss of biodiversity.

As veterinary professionals, I believe we must recognize that protecting animal health means protecting the environment in which they live. We must advocate for policies that prioritize ecosystem health, species protection, and sustainable practices. This means working with other health professionals to address global challenges such as wildlife conservation, habitat destruction, and the impacts of human activity on the natural world.

By embracing the principles of One Health, veterinarians can help ensure a healthier, more sustainable future for both animals and humans and the AVA policy on wildlife trade stands to underpin this.

So, what steps might we look to support as a profession? The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has played a crucial role in regulating the international trade of endangered species. However, is it fit for purpose? As recently highlighted by the CITES Secretariat the system is becoming increasingly ineffective in addressing the growing threats to biodiversity. A statement released by the Secretariat in the run in to COP20 in Uzbekistan later this year suggests CITES can no longer keep up with the work it is designed to do. That it has reached, “a critical point, where addressing the increasing demands and expectations of every issue simultaneously has already gone beyond the capability of the Convention’s operational framework. The current mode of work is no longer viable or sustainable…..”

Australia has long advocated for the adoption of a precautionary principle in wildlife trade regulation. The idea is simple: if there is uncertainty about the impact of a trade practice on a species, we should take action to protect that species until we have enough data to make informed decisions. This precautionary approach has been a part of Australia’s international wildlife conservation policy since the 1980s. It was Australia in 1981 who first proposed the adoption of the precautionary principle with a Reverse Listing proposal – everything it said would happen under the current model is indeed happening. Nearly 45 years later maybe it is time to revisit their prophetic wisdom and I believe the profession would do well to be supporting a push to see CITES modernised to become fit for purpose.

Today, the veterinary profession has an opportunity to lead the call for reform in CITES and similar systems. We must advocate for greater transparency in wildlife trade, electronic permitting, and traceability from source to end use. This will ensure that trade practices are sustainable and that we can track the impact of trade on species health and biodiversity.

We also need to ensure that the trade of wildlife and wildlife products is aligned with the principles of One Health—recognizing that the health of animals, humans, and ecosystems are all interconnected. By pushing for a modernization of CITES, veterinarians can play a critical role in protecting the future of global biodiversity.

As veterinarians, we care deeply for the animals we treat. But to truly make a difference, we must broaden our commitment to animal welfare. It’s time for a new oath—a pledge to protect not just the individual animal in front of us, but all species and ecosystems. Our responsibility extends beyond the walls of our clinics to the health of the planet itself.

The new policy from the AVA on exotic pet and wildlife trade is a step in the right direction, but it is only the beginning. As veterinarians, we have the expertise, the knowledge, and the moral responsibility to advocate for more significant changes in the way we treat animals, protect species, and conserve our environment.

Will you take this new oath with me? Will you stand up for a broader vision of animal welfare—one that includes the welfare of species, ecosystems, and the planet we all share?