A key part of the marketing strategy of luxury apparel and accessories is that there is a “story behind” the item you buy, “it has a history”. Well, the story and history behind the luxury trade that uses endangered and exotic species as raw materials for bags, shoes, jackets, and accessories, is one of unchecked exploitation. This has only accelerated with the emergence of the superfake.

Periodically, the scandal of superfakes hits the news. In 2023, a national fashion editor in Australia wrote, “The lump in my throat grew larger as I recalled my friend’s instructions. From the lift, count five shops to the left; if you hit the yum cha restaurant, you’ve gone too far. It was 2005, and I was standing in a shopping centre in Shenzhen, China, having taken the train from Hong Kong – a journey thousands of Australian tourists make each year. My Chinese-speaking friend had instructed me, upon entering the store, which was stacked floor to ceiling with Hermes, Chanel and Burberry, to ask for the “export quality” bags and wait. [I then went on] a wild orienteering course through the shopping centre’s stairwells to the roof, down a seemingly dead-end corridor and, after rotating an electric switchboard that is actually a door, into a room that to a “superfake” bag lover can only be described as heaven. Yes, I once trekked to China to buy superfakes, the high-quality fake handbags, So, why the confession? Well, first to demonstrate that there was a time when I wanted a designer bag so badly that I was prepared to buy a high-quality fake for a few hundred dollars instead of the thousands commanded by the genuine article. But, also, to acknowledge that I, too, was once naive enough to think that my purchase of a fake was an innocent, victimless crime”.

The editor goes on to name the victims, the workforce which may be caught up in modern-day slavery, the luxury brands whose trademarks and bottom lines are eroded, the consumer, who “just want to treat themselves a little”. The victims she seems oblivious to are the endangered and exotic species that are been decimated to create these “treats”.

The global scale of the superfake threat to wild species was highlighted in an ABC US segment on the seizure of counterfeit goods going into the USA. It details:

- 24,604 counterfeit handbacks/wallets seized in 2023, with a retail value US$656.72 million.

- 32,818 items of Wearing Apparel/Accessories, with a retail value US$451.01 million),

- 16,059 items of Watches/Jewellery – exotic species are used in watchstraps, with a retail value US$1,060.79 million, and,

- 11,948 items of Footwear – (excluding sports shoes) – with a retail value US$60.53 million.

A significant percentage of the 85,000 items confiscated in a single year would have used endangered or exotic species in their manufacturing process. Using the Endangered Species Act as a basis for seizures of goods by US customs is very common, as evidenced by the data in the LEMIS. In total over US$2.2 billion in counterfeit goods was confiscated at the US border in 2023. And, let’s be honest, a lot more would have got through customs than was confiscated to be sold on the streets of Manhattan. But this isn’t only a US problem, the same thing is happening in Europe, Asia and, indeed, worldwide.

So why is there a burgeoning market in superfakes? Demand is one side of the story, not everyone fawning over luxury handbags and shoes can afford the genuine article (which is the point of luxury). The other side is the lack of transparency in supply chains, which makes it possible to obtain the raw materials, which include CITES listed species like crocodiles, snakes, lizards, rays and even giraffes and elephants. Part of the problem is that it is laughingly easy to launder illegally obtained skins of these animals into legal supply chains. National enforcement of CITES listings ranges from low-priority, to underfunded, all the way to non-existent.

For example, a 1990 review of supply-side countries in Asia discussed, that collecting pythons for the skin trade had adversely affected populations. While the report admitted the population impact of harvesting skins could not be evaluated in detail, it did highlight some of the key loopholes in the monitoring system that could be exploited, and finished by saying a levy system should be investigated because there was evidence that the true value of skins was ‘substantially under-declared’. Jump forward to 2014 and a report Assessment of Python Breeding Farms Supplying the International High-end Leather Industry acknowledges that absence of strong regulatory measures, monitoring and enforcement, giving examples such as, “Despite large exports of python skins from Lao PDR with a CITES source code C [captively bred], this study found no evidence that python farming is currently taking place [in the country]”.

There is certainly reason for concern about the scale of illegal poaching of pythons. As far back as 2016, Chinese authorities recovered a massive haul of 68,000 smuggled python skins worth $48 million which was described, it the time, as the “largest-ever python skin smuggling case”. But there has been no significant investment in supply chain management for this highly lucrative trade. Businesses don’t care because there is no pressure.

As I write this I am reminded of an experience told to me by a friend, working in the Melbourne fashion industry. He was in China, over a decade ago, scoping out potential manufacturers for the company he worked for. While getting a tour at one potential supplier, all of a sudden everything stopped. Many metres of textiles, used in the manufacture of bags, were removed from the production process and set aside, as were chains and zippers. Then everything started again. Obviously the production line manager hadn’t got the memo that visitors were in the factory. What had my friend just seen? He had seen that the ‘real’ bags and the ‘counterfeit’ were made of the same materials, by the same people, in the same factories. The current tariff disputes between the USA and China have put the supply chain problems for luxury goods back into the news and show how hard it is to independently verify the true situation.

When it comes to the use of endangered and exotic species in the supply chains of luxury goods, there has been no investment in improving monitoring and regulation. Instead, the global industry of ‘authenticators’ is growing, even though luxury brands might not welcome this. Because the luxury brands benefit from the superfake market (it drives up demand for the real thing. which allows them to further increase prices), they have no incentive to invest in cleaning up their supply chains. This includes the laundering of illegally obtained skins into their manufacturing operations. Because the volume of the superfake trade is unknown and because there is no way of knowing the scale of laundering, we really have no idea about the additional pressures this brings on wild populations of pythons, crocodiles and so on.

The failure of supply chain management and transparency, enabling industrial scale green crime represents a failure of business, industry, markets and investors. This is driving the Age of the Superfake. But it isn’t the only problem.

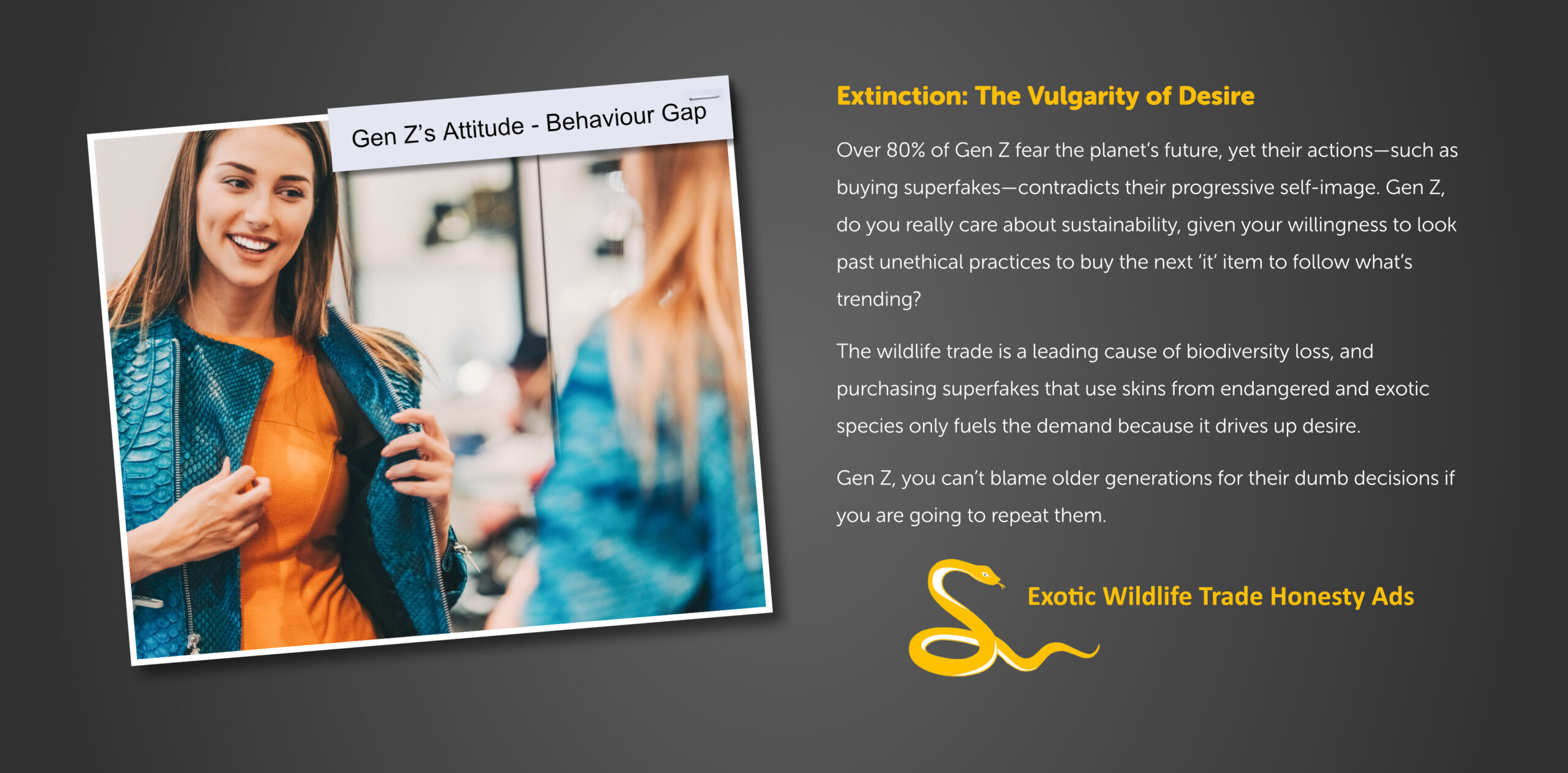

Gen Z’s Attitude-Behaviour Gap

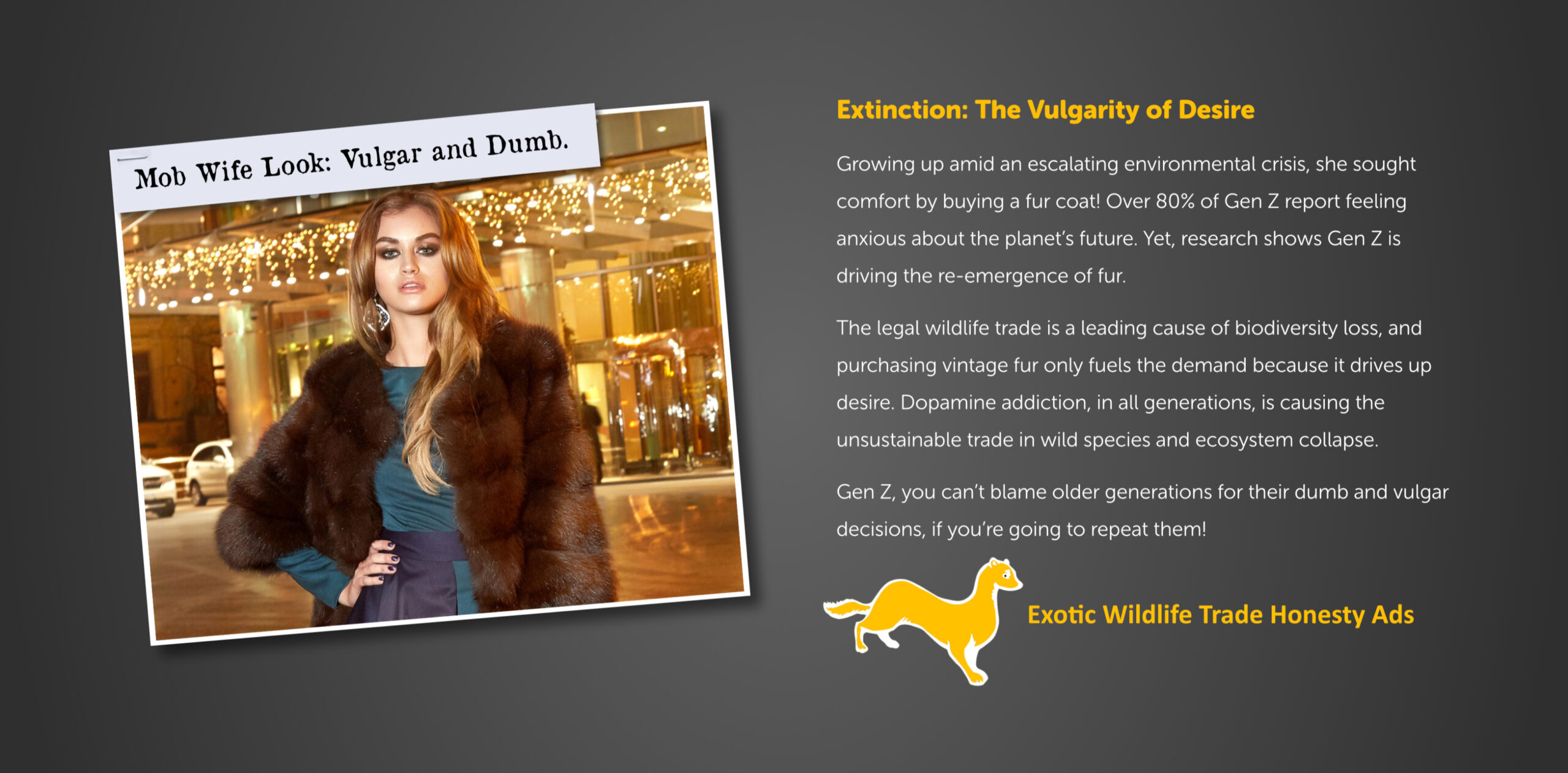

If the desire for exotic skins and fur were was dropping maybe we could just wait for this industry to become extinct, but it isn’t. Luxury items that use exotic species are endorsed by celebrities and influencers, including A-listers, and, worse still, superfakes are endorsed as OK to purchase. What is interesting is that Gen Z is driving much of the acceptance.

In a 2023 article for Fashion Journal, Dr Marian Makkar, Senior Lecturer in Marketing at RMIT University, tells the journalist, “It is true that Gen Z has a strong commitment to sustainability where 82 per cent have concerns about the state of the planet”, continuing, “But this attitude towards sustainable causes comes into conflict and contradiction with their actions when it comes to superfakes”. This is what’s known as an attitude-behaviour gap, when someone’s values don’t reflect their actions. “They may care about the environment and some social causes, but they do not see the connection that buying superfakes is illegal, unethical consumption behaviour”.

Is this lack of connection a genuine lack of awareness or simply selective ignorance when it comes to everything from superfakes to ‘mob wives’ fur? Because, Gen Z, you can’t blame older generations for the dumb decisions they made, if you’re going to repeat them.

The next time the crime of superfakes hits the news, check out the victims that are named in the article or segment. Does the journalist include the endangered and exotic species that are been decimated to create these fake luxuries?