Over the years of researching the CITES listed legal trade in wild species, periodically the question arose, “What if Jeff Bezos ran Amazon Inc. with the same supply chain processes as the CITES?”.

Amazon Inc. is a perfect contrast of what can be achieved when it is in the business’ interest for supply chains to be well monitored. Amazon runs 175 fulfilment centres across the globe and stocks hundreds of millions of items, so the complexity of the trade is not the issue when it comes to real-time monitoring and tracking.

In stark contrast, the CITES trade management processes, based on a 1970s paper-permit system, is what happens when businesses would rather keep you in the dark about the scale of their exploitation of wild species. Compared to Amazon, CITES only manages 41,000 species and monitors 183 border crossings – again complexity is not the issue.

I always feel the best way to understand the how the CITES processes are stuck in the 1970s is to put yourself into the shoes of Detective Inspector Sam Tyler when, in Life on Mars, he is transported back to 1973 (coincidently the year the CITES was first opened to signatories).

The CITES trade management system is equivalent to Amazon having no idea what products are in stock anywhere, when they will next arrive, where they come from, who provided them, who they go to and the only tracking updates you ever get come from a border crossing, albeit up to several years after the event.

Don’t believe me? Take a look at the CITES trade supply chain monitoring and management system and see for yourself.

As long as the trade in CITES species is not tracked, and radically transparent, in real time, and from source to destination, monitoring and regulation under the CITES is nothing more than illusion and delusion.

Yet conservation agencies keep repeating that CITES is effective. I wonder if customers would say Amazon Inc. is effective if it operated like that? I think not, the company would have gone out of business very quickly if its supply chain management used the same processes as the CITES!

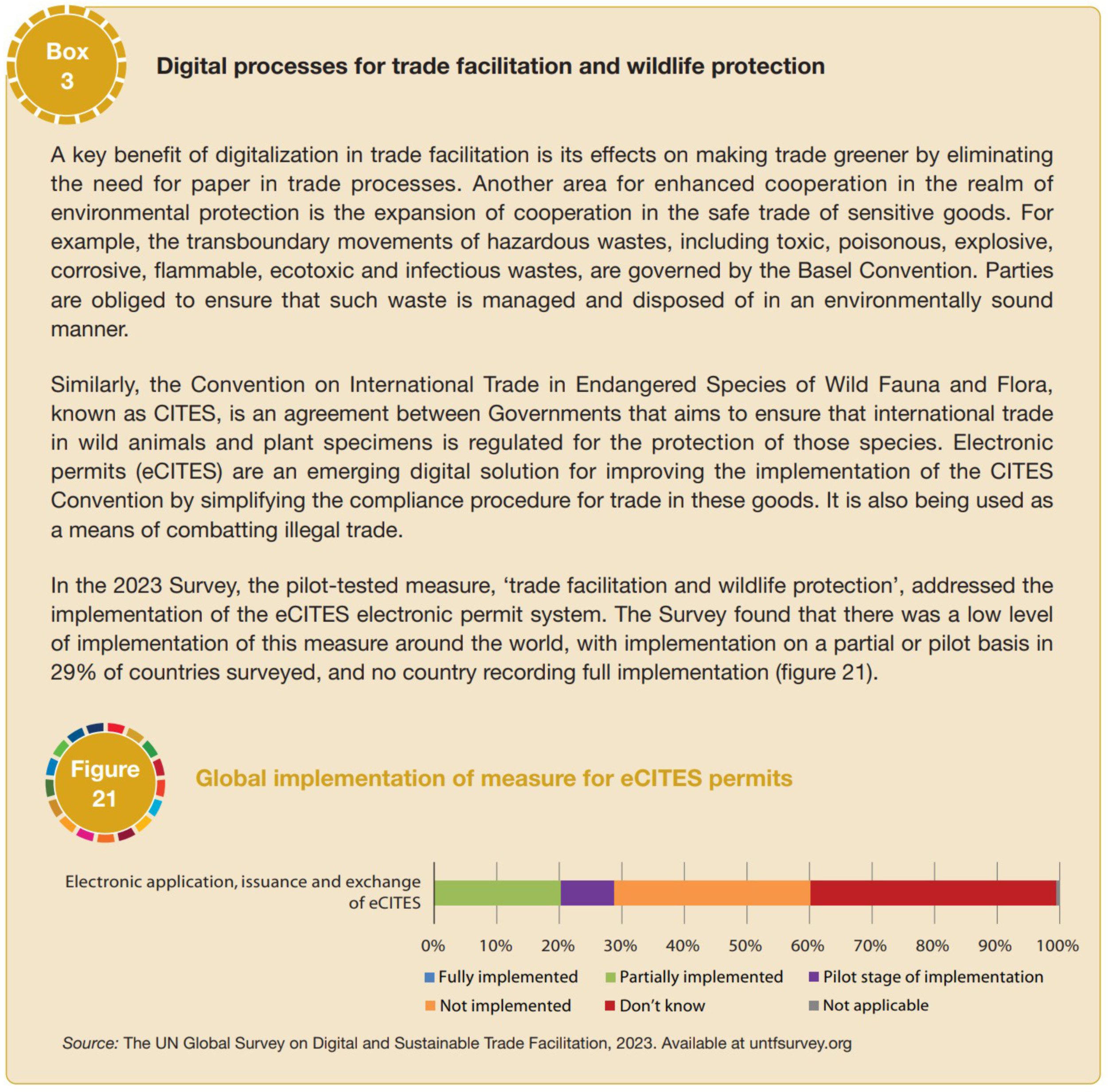

The UN Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation Global Report acknowledged that when it comes to a digital process for trade facilitation and wildlife protection, there was a low level of implementation of the CITES electronic permits (eCITES) and as such no country could record full implementation.

Even if every country adopted electronic permits, which would be a great first step, we would still have no tracking from source to destination, no information on source, and no real-time data collection.

As a result of this giant loophole of a trade ‘monitoring’ system, big business and their investors are enabled to profit from an unchecked global legal trade in endangered and exotic species. This is particularly tragic given the tech that the CITES needs to monitor supply chains, in real time, has been available for years; namely microchips and QR codes.

The investment required to implement electronic permits, electronic permit exchange, tagging/microchipping and real-time reporting is pocket change compared to the profits that are being made by some of the wealthiest business brands in the world, including by Amazon Inc. Many products made from CITES listed species are sold on Amazon.com; when I see them and read Amazon’s meaningless Sustainability Reports, it certainly doesn’t make me smile!

It seems utterly bizarre that recently one corporate conservation organisation made the statement, “Furthermore, the introduction of concepts such as traceability confuse the core mandates of CITES”!! Adding traceability is a requirement for supply chain transparency, and not something that ‘confuses the core mandate’ of CITES. Makes you wonder what they are trying to hide?

Even with their evidence-based mantra, when it comes to the legal trade in wild species too many conservation organisations are willing to sidestep George Henry Lewes recommendation of, “We must never assume that which is incapable of proof”.

Without traceability there is no information on the true source of a shipment, no way of verifying that the specimens where captive bred or wild caught, and no way of knowing the actual offtake numbers that led to whatever ‘product’ is being shipped. CITES is completely flying blind and, let’s be honest, that’s on purpose. Difficult to comprehend that this could have been allowed to happen, I know.

Most people associated with CITES/conservation are biologists and ecologists. How do they expect to manage sustainability without any way to know actual offtake numbers? Why have they been so unwilling to expand their professional development to understand global trade system, luxury markets etc.? Why will they not talk about the massive amounts of money involved in the trade?

There is no evidence that they are willing to do any of what is needed. Conservation agencies involved in CITES are happy to put their hands out for funding from business but not willing to learn what they need to balance out the power differential when it comes to lobbying and closing the loopholes. Maybe they keep talking about CITES being effective to hide the fact that they have been ineffective when it comes to dealing with the abuse of the legal trade.

To fix the abysmal state of the CITES trade management system, the very first step is to set a date for the mandatory implementation of electronic permit systems for all signatory countries, and high-income countries must make funds available to low- and middle-income countries to modernise their systems. Once that date is reached, any country that still uses the 1970s paper-permit system is automatically suspended from CITES trade.

The second step is the implementation of electronic permit exchange, centralised monitoring and real-time reporting of trade. These will all be easily possible based on the first step and should equally become mandatory.

With this baseline in place, real-time tracking from source to destination can be introduced for Appendix I species, high-value Appendix II species and later progressively all species traded under CITES.

None of this is hard or even overly expensive, what is required is political will, pressure from conservation agencies and academics, and get businesses to provide the funding via a levy on trade. The ONLY reason the CITES regulation hasn’t kept pace with supply chain technology over the decades is that it is in the interests of businesses to keep customers in the dark about the scale of their exploitation of wild species. That corporate conservation has capitulated to business interests is unforgivable.

This is the reality of the CITES@50. Until this is addressed, the CITES will continue to live in its 1970s time warp and the legal trade in wild species remains a horror show.