Given the CITES trade measures have never been enforced, the valid question is, has the CITES ever really been a regulator of the trade in wild species?

That CITES is believed to be a regulator in not in doubt. In a briefing session, John Scanlon, who was Secretary General of CITES between 2010 and 2018 summarised the CITES this way, “CITES is a convention of the 1970s. It is focused on a very specific issue, in this case regulating international trade in wildlife to protect against over exploitation from international trade. [CITES Parties] have preferred to maintain the narrow focus of the convention”. He continued, “CITES regulates trade in certain species to ensure the trade is legal and not detrimental to the survival of that species…It seeks to ensure that any such international trade is sustainable…. So, what is CITES? It is both a conservation and a trade related convention. It uses trade related measure to achieve its conservation objective, namely protecting certain wildlife against overexploitation for international trade and in doing so it contributes towards achieving sustainable development”.

Scanlon talks about the CITES mandate being narrow, “in this case regulating international trade in wildlife to protect against over exploitation from international trade”. Narrow shouldn’t mean useless but the fact that an Enforcement Authority wasn’t mandated to signatories as they signed up to the convention, it effectively made the CITES useless from the very start.

Because no enforcement was mandated, this means that there has been no verification of the “trade related measure to achieve its conservation objective” Scanlon talks about.

For CITES to be a regulator, verification of its trade related measures should be enforced and enforced every step of the way. But under the CITES this is left as an ‘optional’ activity for signatory countries to decide if they do or not.

This fatal flaw in the design of the CITES cannot be addressed until we collectively stop thinking about enforcement as dealing with poachers and transnational organised crime, which is where all the focus under CITES tends to be in the minds of governments and conservation agencies.

In the first instance enforcement needs to be about enforcing the trade related measures of the legal trade. It is the fact that this has never been done that makes poaching and transnational organised wildlife crime so easy. But no one wants to do this because it will reduce profits.

As a result, legal and illegal trade in endangered and exotic species are so intertwined that they are currently functionally inseparable, and no one wants to work on the needed decoupling. Even after businesses worldwide have openly acknowledged the scale of green crime in their supply chains.

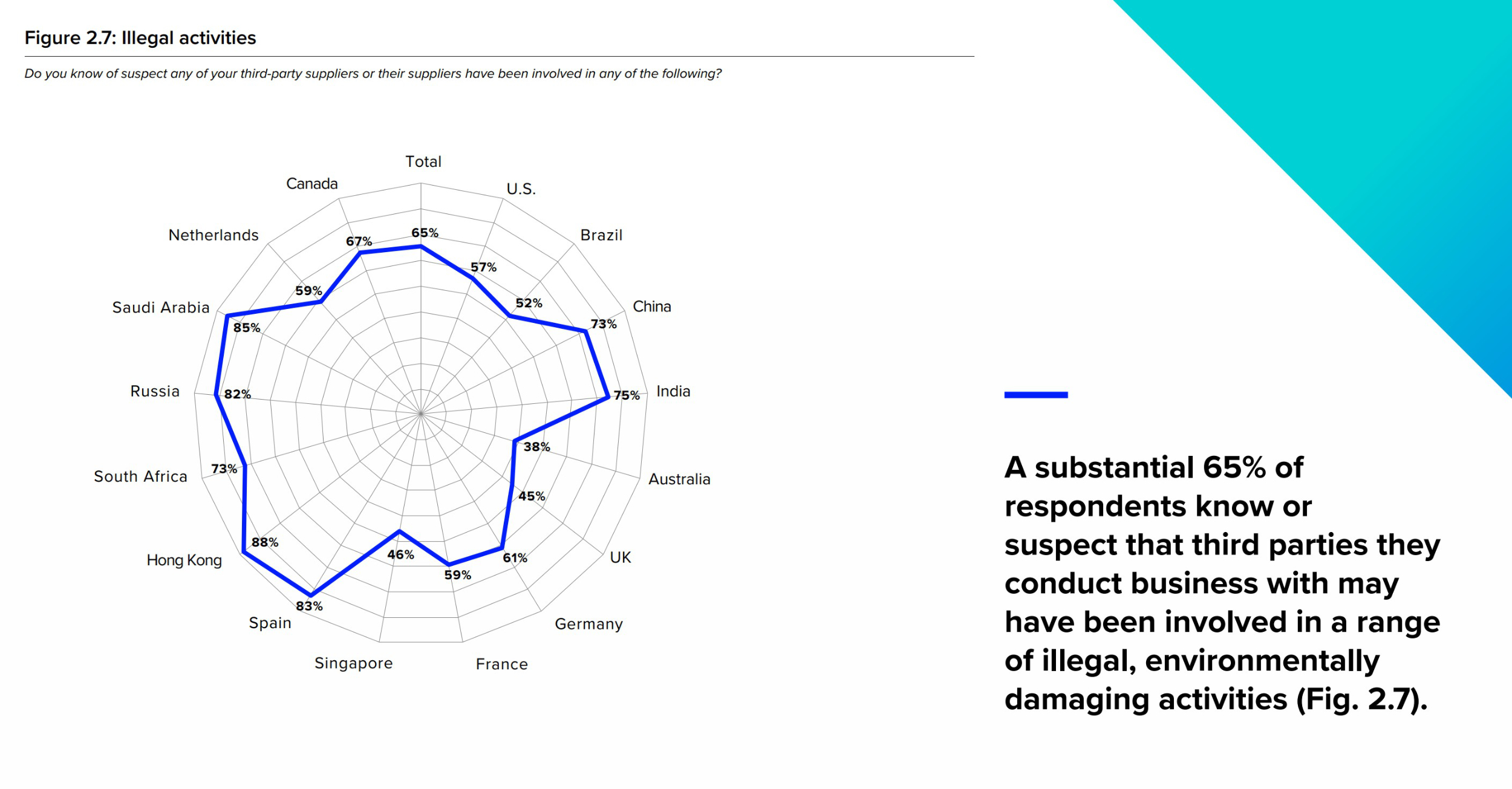

A report on green crime published in early 2020 by Refinitiv provides information about how the global system of trade is enabling industrial scale environmental damage.

A substantial 65% of respondents know or suspect that third parties they conduct business with may have been involved in a range of illegal, environmentally damaging activities. This was much higher in individual countries including Spain (83%), Hong Kong (88%), India (75%) and Saudi Arabia (85%).

Only 16% of global respondents say that they would report a third-party breach externally. In reality, we are depended on integrity of company whistleblowers to bring these crimes into the light, when we they should be uncovered by regulators, and ideally deterred because of the quality of enforcing the trade related measures.

There are numerous ways in which the CITES rules are not enforced. Because country MAs only tend to have a tiny number of employees, generally information on permit applications is not verified. If the exporter says the shipment will consist of ‘captive bred’ animals, nobody will go and check (or maybe only the first time a new business gets registered). This equally applies to all other information on a permit application.

Further, unless the country uses eCITES, even the most basic checks for nomenclature, compliance with CITES rules (such as units), or consistency of the permit information are not carried out or are carried out poorly.

And rather than getting excited about more species being listed for CITES trade restriction, it should be noted that the quality of verification has gone down over the years, as the number of species the CITES lists has gone up.

A paper published in 2015 outlined the prevalence of documentation discrepancies in CITES trade data for Appendix I and II species exported out of 50 African nations (to 198 importing countries/territories) between the years 2003 and 2012. The data represented 2,750 species.

Of the 90,204 original records downloaded from the database, the increases in discrepancy-rates between 2003 and 2012, suggested that the trade was monitored less efficiently in 2012 than it was in 2003. In total only 7.3% were free from discrepancies.

So, yes, laughable easy to launder illicit ‘product’ into the legal supply chain. Businesses don’t care, nor do those involved in transnational organised crime.

Given that there is so little appetite to deal with white-collar/corporate crime, this means that nothing decisive can be done in dealing with transnational organised crime.

This is born out with a number of recent admissions. The first example from RUSI, Evolve or Perish? Global Action on Illegal Wildlife Trade, acknowledging, “Over a decade, our collective endeavours have driven IWT up policy agendas. Enabling large-scale programming worldwide, such a radical transformation in thinking and action around a single crime has seen few parallels across other illicit markets. Tangible results have been seen for some species, resulting from supply and demand-side action. Yet fundamental challenges remain: 10 years since global signatories first gathered in London, and despite the scale of investment, our collective impact on the overarching threat has been limited”.

Another example is even more telling, with recent research confirming, Environmental crime is being overlooked by global enforcement systems. Environmental crime remains a low priority for international law enforcement:

- Only 2% of Interpol Red Notices target environmental criminals.

- Out of more than 7,000 Interpol Red Notices — alerts used to locate and arrest fugitives — only 21 relate to environmental crimes.

- Offences like illegal logging, wildlife trafficking, and pollution are largely ignored by global enforcement.

Just how many networks have been created over the last 10-20 years to deal with wildlife and environmental crime? Their collective failure was predictable, because crimes can’t be solved when key suspects are taken out of the frame.

When it comes to wildlife crime enabled by the ease of laundering illicit product in the legal supply chains, there is no desire to peer behind corporate and regulatory façades. Until we are collectively willing to look at the systemic failure of legal extraction and consumption of wild species, and how this is regulated, we can’t prove beyond reasonable doubt what is driving biodiversity loss.

CITES shouldn’t survive if an Enforcement Authority isn’t made mandatory. A date for mandatory implementation of an Enforcement Authority in all signatory countries must be set and businesses in the major import markets must face a levy to cover the costs of enforcement throughout the whole value chain. If an enforcement authority isn’t in place by the agreed date, trade sanctions must be applied to all exports, imports and re-exports from the country. The illusion and delusion of CITES effectiveness must stop.