In this third article investigating Australia’s role in the exotic pet trade, Dr Cameron Murray takes a dive into how Australia supplies the aquarium trade. To read the investigation in full:

Article 1: Petted To Death, introduces Australia’s little known contribution to the extinction crisis.

Article 2: Australia’s Exotic Pet Trade Is Both Surprising And Rising, discusses the blurred boundaries between the legal, legalish and illegal trade.

In this third article, exploring Australia’s role in both the legal and illegal exotic pet trade, I head to the ocean and under the waves; diving into the back story of the world of Nemo. Those that have seen the original film will remember how the famous clown fish was plucked from the safety of the reef by fishermen to end up in a dentist’s aquarium. The story has a happy ending with Nemo’s escape and return to his dad on the reef but maybe it has a deeper side than the lighthearted family entertainment it offered at the time.

Australia’s largest contribution to the international exotic pet trade is through the legal trade of species for the aquarium industry. This is primarily through the trade of ornamental marine fish, other marine species and coral, including species unique to Australian waters. In the case of coral, much of this is CITES listed, though this doesn’t guarantee it is well monitored or regulated. As with many other marine species, very few of the ornamental fish species are listed under CITES. Direct exploitation (read TRADE) is the biggest threat to marine species and so it is an anomaly that so few marine species are listed for trade restrictions.

There are three main contributing states to Australia’s domestic and international aquarium trade. Queensland – by far the largest contributor, the Northern Territory (NT) and Western Australia (WA). In addition, Tasmania is home to our main supply of captive bred seahorses.

In the case of Queensland this contribution comes largely from the Great Barrier Reef, a UNESCO listed World Heritage site. In 2021 UNESCO was concerned enough about the health of the reef system that it recommended consideration of placing it on the, “List of World Heritage in Danger” in part due to overfishing. In 2023, Audrey Azoulay, Director General of UNESCO said, “The Great Barrier Reef is a fragile jewel of world heritage. For many years, UNESCO has not ceased alerting the world to the risk of this site losing its universal value forever. We have proposed several concrete measures which provide a roadmap for tackling the problem.”. These concrete measures include, “Create no-fishing zones in a third of the World Heritage site by the end of 2024”.

As a result the Australian government committed to a range of actions to address UNESCOs concerns. The question could be asked as to whether the additional burden of fisheries such as ornamental fish/coral for the supply of a luxury market is adequately monitored and managed?

As introduced in previous articles in the series, the Australian government’s Aquaplan quotes a 2015 value of AUD$350 million for Australia’s ornamental fish industry. So, let’s look at some details around this trade.

There are more than 1,500 marine fish species that could be harvested from Australian waters for private or public aquarium displays.

Queensland

- Queensland issues 49 licenses for the purpose of harvesting marine fish species for the aquarium trade – 43 of these were active in 2022

- Queensland issues 59 licenses for the purpose of harvesting coral for the aquarium trade – all were active in 2022

- The Queensland fishery is not a quota managed fishery but rather each license is allotted a portion of an overall Total Allowable Catch (TAC)

- In Queensland boats must report catch and effort, plus any contact with threatened, endangered and protected species. A vessel monitoring system (VMS) to track their vessels’ movement must be used.

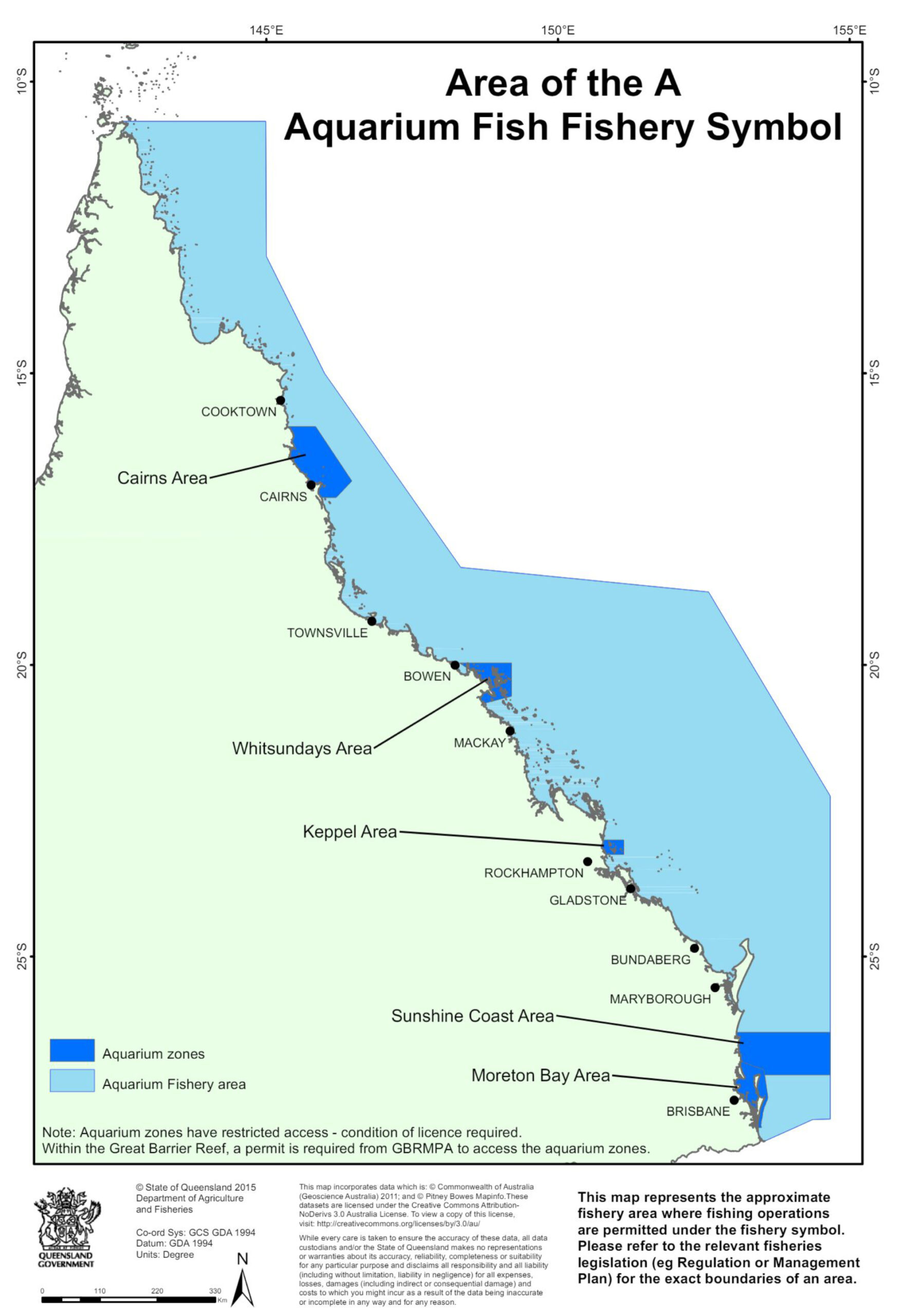

In the case of Queensland the fishery zones are broad as shown on the map.

Of the many marine fish species that can be harvested from Queensland some species have a broad distribution while others are endemic to the regions from which they are fished. In the case of corals, often the uniqueness of the specimens significantly increases their value and demand from export markets. The fish families important to the aquarium trade include:

- Damselfish (family Pomacentridae)

- Butterflyfish and bannerfish (family Chaetodontidae)

- Angelfish (family Pomacanthidae)

- Wrasses (family Labridae)

- Surgeonfish (family Acanthuridae)

- Gobies (family Gobiidae)

The data available around catch volumes and effort are also interesting.

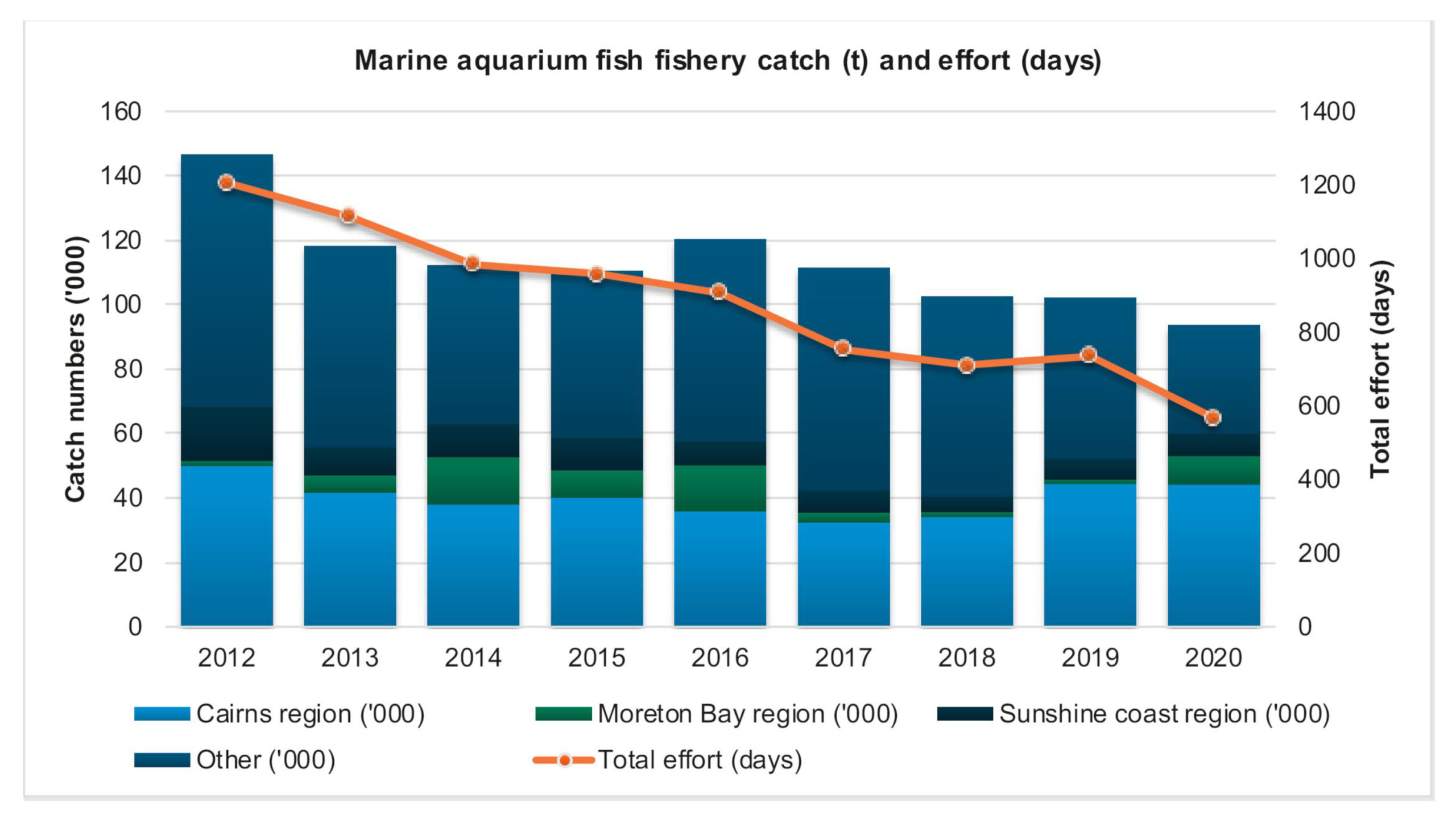

In the case of Queensland, it appears the catch volume of fish has declined over the last decade and associated effort proportionally.

In the case of coral the fishery targets a broad range of species from the classes, Anthozoa and Hydrozoa. Key components include:

- hard corals

- soft corals

- sea anemones

- live rock (dead coral skeletons with algae and other organisms living on them)

- coral rubble (coarsely broken up coral fragments)

- coral sand (finely ground-up particles of coral skeleton, which fishers can only take as incidental catch and must not target in marine park waters).

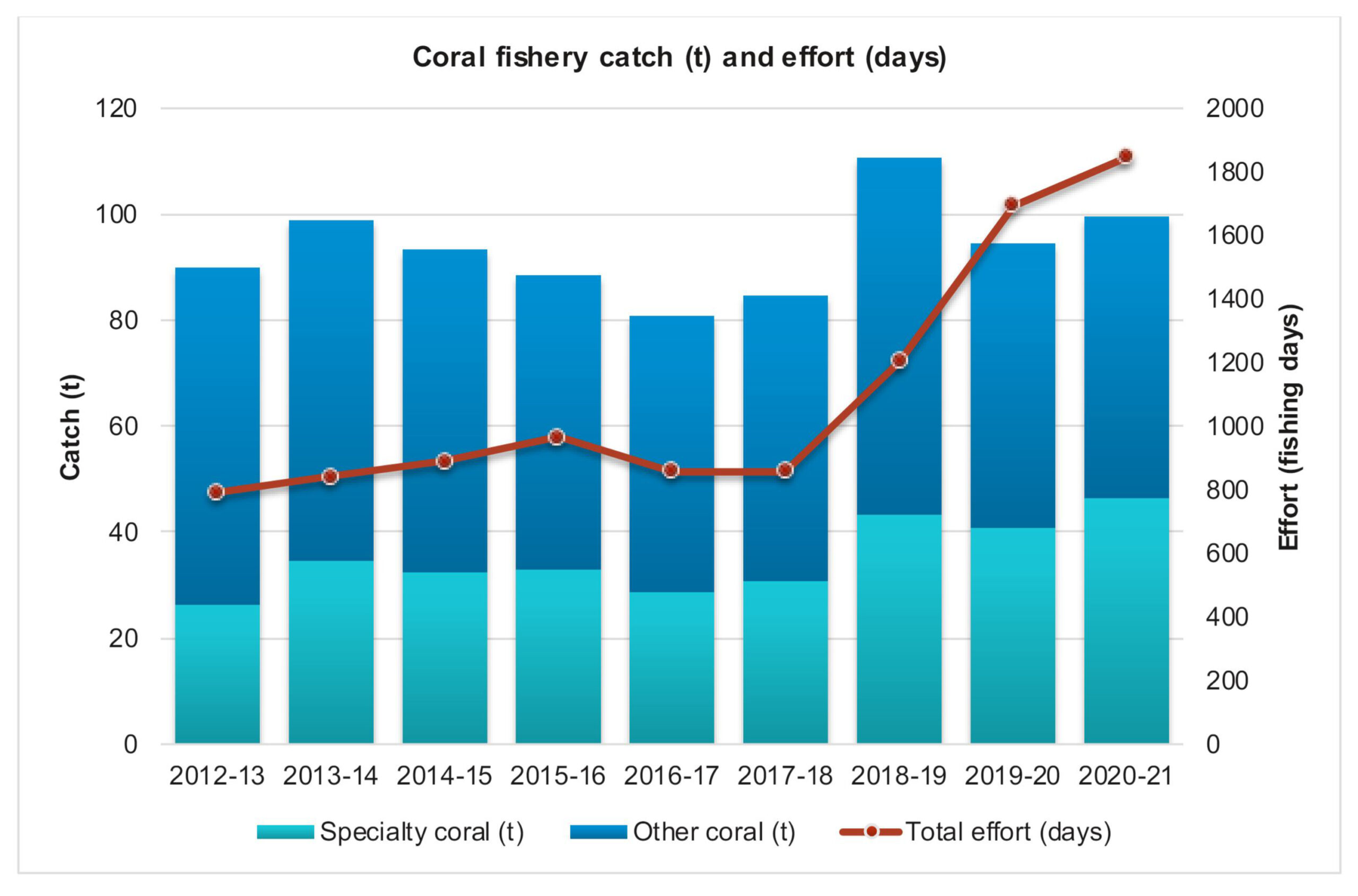

In the case of Queensland’s coral harvest, volume has been relatively consistent over the last decade, however, the effort figure associated with this catch has proportionally increased. This could be construed to mean that depletion of stock results in increasing catch time. However, on speaking to a representative of the Queensland Department of Fisheries it seems the most likely reason for this increased effort is the move toward specialty coral species collection, which are more profitable.

Selective coral harvesting means more time spent to find certain rarer corals or colour morphs of coral that attract higher pricing in the aquarium market. This drive toward speciality corals has led to steps to alter the quota system to avoid increased selective pressures on select species and the risk of local depletion in those areas most easily accessed and fished.

As of December 2023, operators must have a Primary Commercial Fishing License ($367.66) and the main operator must have a Commercial Fisher License ($367.66). In addition, the fisherman must hold an Aquarium Fish License (A1 $426.49, A2 $139.71). In the case of corals an additional quota fee of $0.07/unit is applicable (whether that is harvested or not). This last figure is quite astounding when you consider the possible value of each unit of coral. You may remember in my last blog I quoted one CITES listed trade event in 2018 for Scoly Coral (Scolymia australis) which allowed the export of 45,620 units to France. Each unit had an expected retail value of US$100-500 meaning the total value of the shipment was approx. US$4.5-25million! The fee paid to mine these millions, outside the $75 CITES permit fee, was just over $3,000!

Northern Territory (NT)

- The NT issues 8 licenses with 1 of these exporting

- The NT fish within a quota limit and the limits are assessed in line with an Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) performed every 5 years, with the next one due in July 2024.

- In addition, CITES listed species may be subject to Non-Detrimental Finding (NDF) reports. The linked ERA outlines for a number of species that the impact of the harvest by the aquarium fishery was considered to be severe, as catches have exceeded the NDF for the species. New catch limits have been introduced with the aim that the negative impact is reduced in future. An updated review has not yet been published.

- The reporting of effort is required in monthly logbooks and vessel monitoring systems are required to track vessel movement.

- As at December 2023 license holders in the Aquarium Fishery pay a flat fee of $1400.

Western Australia (WA)

- In WA a 2023 report states there are 11 active fishing vessels of 12 and 2 active of 5 harvesting hermit crabs. These licenses cover all marine aquarium species inclusive of fish and coral.

- In WA license holders fish within a quota limit.

- License holders must record catch and effort daily with the final catch weighed and reported on landing. There are no vessel tracking requirements.

- The licensing cost is $2012 in addition to the licensing of the boat ($85-$315). In addition, a fee of $0.04-$0.39 is paid per unit depending on the target species.

- Also of interest is Western Australia’s Hermit Crab Fishery (HCF) – Coenobita variabilis, endemic to the northern parts of Australia – which operates from the Exmouth Gulf to the Northern Territory border all year round; this is a land-based fishery. I was informed that exact volumes couldn’t be openly reported due to commercial in confidence provisions based on only two fishing licenses being active. The historical catch range for the period 2010-2022 was 50,000 to 106, 000 individuals annually. In the case of one Federally approved export permit for these crabs the operator is licensed to export up to 20 000 individuals. No effort data is reported annually for the HCF or aquarium fish industry in WA.

Further information on the WA industry can be sourced here.

In the case of all three state fisheries, reporting of details such as effort and catch are self-reported with only random verification steps performed at the point of catch and landing and subsequently with regard the paper trail and its accuracy. While available, digital reporting is not mandatory, meaning that in some cases it can be months before any audits occur, if ever.

With regards to compliance, the costs of this are borne fully by the State governments. The fees associated with licensing are insufficient to cover the real cost of monitoring the fisheries. The questions I would ask are, are the fisheries being monitored at an appropriate level and in the case of the aquarium trade fisheries, is it appropriate that the taxpayer should be paying to police these businesses supplying a luxury market?

Logistically it would appear to fully monitor and manage these fisheries a far greater number of people on the ground and investment in resources is needed. I was told, Queensland for instance has only one large offshore vessel capable of longer monitoring trips. This lack of manpower and resource means there are no targets set for the number of random inspections that occur and inspections are based on risk assessments and intelligence.

Anecdotally, I was told of one fishing license holder in a niche market in Queensland that despite many years of operation has never been physically inspected. In addition, in the case of the coral fisheries the move to a more species-specific collection based on the desire for specialty corals means that very few people have the skills and knowledge to identify corals to a species level. Corals are notoriously difficult to ID and as such the skill levels and training are reportedly inadequate to even assess compliance in these cases.

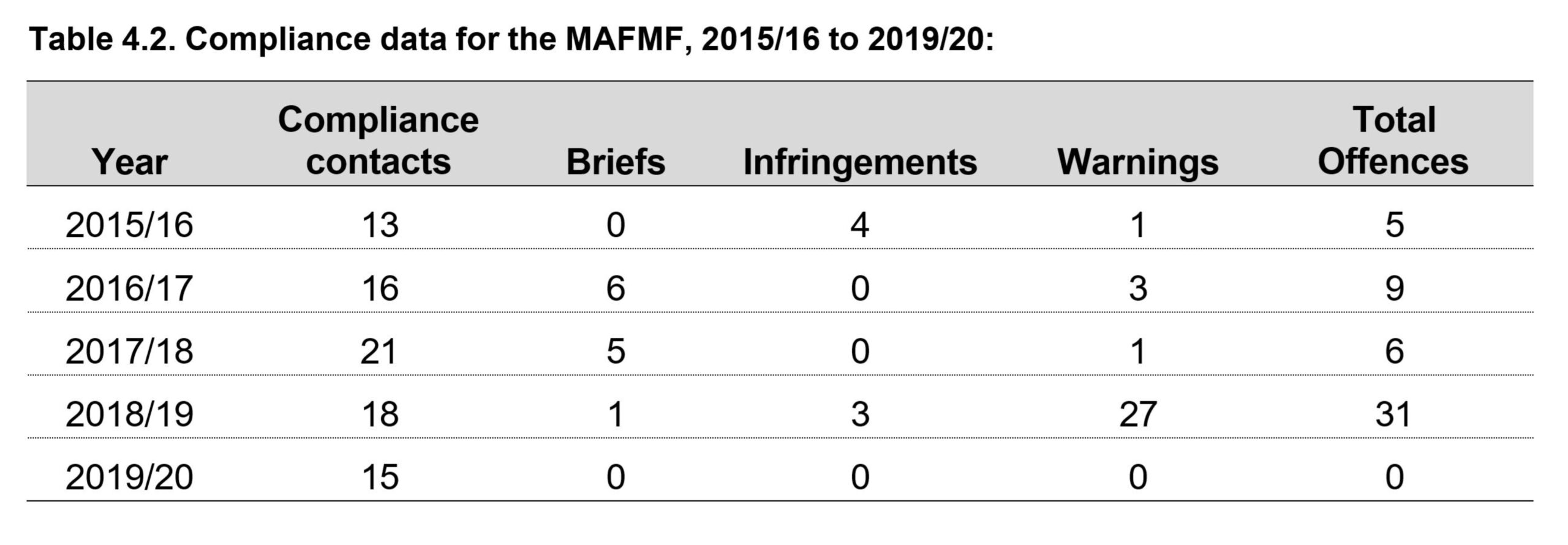

The figures around compliance reports are interesting also, although at times slightly hard to generate. In the NT there are no compliance reports due to concerns around commercial confidentiality due to the low number of license holders. In WA there is a publicly available compliance report related to the Marine Aquarium Fish Managed Fishery (MAFMF). This shows for the period 2015/16 – 2019/20 there were between 13-21 compliance contacts annually.

Remember this is for a fishery of 13 active licenses meaning that on average WA license holders can expect compliance contacts once to twice yearly. Also interesting is that on average for every compliance contact there is an offence reported roughly 60% of the times. This is likely skewed based on the intelligence driven inspection process but nonetheless represents a high proportion.

In Queensland, no accurate figures for compliance reports related directly to the Marine Aquarium Fishery (MAF) are available publicly. Rather, reports reference all the fisheries combined. A request for data directly related to the MAF resulted in a direction to proceed through the cost incurring Right to Information process with no guarantee of data, again due to commercial sensitivity concerns.

So, the supply of the worldwide aquarium industry from Australia is significant. It raises questions though. A recent article, Calls for change as tonnes of coral taken from Great Barrier Reef highlights concerns with regard the sustainability of the this trade for a variety of reasons and quoted Professor Morgan Pratchett, marine biology and aquaculture professor at James Cook University, saying, “A good understanding of wild stocks’ status and their sensitivity to non-fishery threats is essential to determine whether harvesting is sustainable.”, continuing, “Presently, the necessary understanding about corals in the QCF is lacking” and “exploitation levels unclear”.

If this is the case in Queensland it is probably reasonable to think that similar comments could be made on the smaller contributors in WA and the NT. And all this is happening at a time when extreme coral bleaching could spell worst summer on record for Great Barrier Reef.

In the coming week CITES will host a workshop, in Brisbane, to consider the conservation priorities and management needs related to the trade in non-CITES listed marine ornamental fishes worldwide. The fact that very few of the ornamental fish species are listed by CITES speaks to the flaws in the current model. Research published in 2019 concluded it takes on average 12 years for a species flagged by the IUCN as vulnerable from trade to listed by CITES for trade monitoring and restrictions (on paper at least); some species have already been waiting 24 years. During this time lag, species can be traded with no or minimal checking. Only when philanthropist or government provide the funds for the research needed to list a species for trade restrictions does it happen. The businesses who profit provide no funding. It would appear that marine ornamental fish haven’t been iconic enough to attract the attention needed to get this work done. This points to why we need a reverse listing model for CITES.

It is only fair not to overrepresent the scale of Australia’s involvement in the supply of the aquarium trade for the EPT. A report for CITES suggests while Australia is home to the second largest number of individual species involved in the aquarium trade, it supplies only 4.3% of the market. However, it is important that Australians are aware that we DO contribute to this luxury market, and it is important on multiple grounds. Namely:

- It means that as a country we should be questioning whether the worldwide systems that oversee the trade in wildlife, of which the EPT represents a nice example, are fit for purpose?

- Are our existing structures and systems adequately resourced to oversee this trade and the trade in wildlife in general, both legal and illegal and are those benefitting from this trade paying their fair share?

- Do we understand the risks associated with the EPT that we are knowingly and unwittingly involved in. That is, is it truly sustainable and are the species involved in it adequately protected?

Over the last 3 articles on the Exotic Pet Trade, and Australia’s involvement in this, we’ve looked at the worldwide scale of this trade and we’ve delved into how Australia contributes legally and illegally. In the next article I will highlight the issues we must consider that are associated with our involvement in the EPT and why as a country Australia should care more about it, from the issues on an individual animal basis and the bigger issues of global relevance and importance.