In a book published recently, Future of Denial, the author Tad DeLay explores the question, “Why do we continue to squander the short time we have left to deal with climate change?” DeLay isn’t the first to lay bare that “capitalism is an ecocidal engine constantly regenerating climate change denial”. Interviewed by The Guardian, he says, “You can’t admit, as a capitalist subject, that there’s little you as an individual can do, and neither can you imagine the end of capitalism”.

If you can’t imagine the end of capitalism the options are either deny reality or accept it but deny personal moral culpability – namely reject the science or commit to pseudo-solutions, gimmicks and greenwashing. Supporting pseudo/phantom solutions is nothing more than virtue signalling, providing what DeLay calls a “comforting fantasy” in which “education and passion will get the job done without mucking up free markets with regulation or central planning”. In the book he explores, “Will capitalists ever voluntarily walk away from hundreds of trillions of dollars in fossil fuels unless they are forced to do so? Unlikely! And, if not, who will apply the necessary pressure?”.

On the same basis then, why do we continue to squander the short time we have left believing that the financial system is willing to accept its role in the climate crisis and ecosystem collapse? Why do global conservation organisations believe that banks and other financial institutions are unaware of what they are doing and just need to be educated about their role? And, once educated about their lack of risk management, they will change from within!

A perfect example of this is the growing number of conservation NGO reports on following wildlife trafficking money trails. One such report, Wildlife Money Trails, funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund, states, “Since the majority of financial transactions linked to wildlife or timber trafficking pass through banks and financial institutions, financial institutions must improve their capacity to detect unusual or suspicious behaviour or anomalies associated with wildlife and timber trafficking.”, continuing, “The report provides advice to financial institutions on risks and characteristics of wildlife and timber trafficking relevant to detecting suspicious transactions.”. And for law enforcement the report states, “One objective of this report is to encourage law enforcement to shift their focus from the sale of individual specimens to instead target those responsible for the ongoing trade, using “follow the money” principles. In this way, law enforcers are more likely to uncover serious, repeated, or transnational organised crimes.”

This is nothing more than closing the stable doors after the neurotic, narcissistic stallion has long since bolted! In the time since the global financial crisis (GFC) there has been no evidence to suggest that even the most experienced wranglers are yet willing or able to corral this particular horse. This is exposed in the documentary, Uncovering HSBC’s Dark Financial Empire: The Untouchable Bank.

USA Investigation of HSBC (2012)#

In 2012 criminal charges were filed in the USA against HSBC Bank for, “its sustained and systemic failure to guard against the corruption of [the US] financial system by drug traffickers and other criminals and for evading US sanctions law”.

In the documentary, former Deputy Federal Prosecutor, Richard Elias, states, “Affiliates of drug cartels were literally walking into bank branches with hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of dollars of US cash, in Mexico, and putting it through the teller window, sometime in boxes that were specially designed to fit through the teller window. And the HSBC employees took it, they deposited it and gave the person a receipt and never reported the conduct and never stopped it. And that didn’t happen once, it didn’t happen twice, it happened systematically over the course of about a decade. There was one occasion, an individual walks into the bank with maybe US$3-4 million dollars and bank employees spent one full day counting it”.

Richard Elias goes on to say, “The bank had been warned repeatedly and consistently by US authorities and by Mexican authorities. They also were told that the US Prosecutors “had recordings from drug lords that said HSBC was The Place to launder money. London knew everything and they just didn’t care”.

HSBC was at risk of losing its licence to operate in USA. At a Senate committee meeting, where bank executives had to testify, Senator Elizabeth Warren asked, “How many billions of dollars do you have to launder for drug lords and how many economic sanctions do you have to violate, before someone will consider shutting down a financial institution like this?”. The Department of Justice wanted to prosecute while the Treasury Department pushed for an amicable settlement.

In an effort to protect the bank and the City of London, Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborn, lobbied the Obama administration on behalf of HSBC; the bank escaped trial. It received a large fine, which Jack Blum, Jurist and former US Senate investigator, calls, “the equivalent of a parking ticket” for the bank.

All this happened on the watch of Stephan Green who became Chairman of HSBC Group in June 2006. Even Green’s successor Stuart Gulliver, said “between 2004 and 2010, our anti-money laundering controls should have been stronger and more effective”. Yet in November 2010, Green was made a life peer. After entering the House of Lords, he was promoted to government by Prime Minister David Cameron and made Minister of State for Trade and Investment in January 2011, a role he held until December 2013. So, during the time the US filed criminal charges against HSBC Bank for, “its sustained and systemic failure to guard against the corruption of [the US] financial system by drug traffickers and other criminals and for evading US sanctions law.”, the man who led the bank over those same years was the UK’s Minister of State for Trade and Investment. George Osborn may have not only lobbied the Obama administration on behalf of HSBC Bank and the City of London but also to save face for the British government.

In the documentary, Jack Blum also says, “This bank had done everything bad that a bank can possibly do… If you don’t prosecute these people, who the hell are you going to prosecute?”.

So, while conservation NGOs write reports stating, “Wildlife and timber trafficking pose a reputational risk to banks and financial institutions to the extent that they expose the bank to participate in money laundering, fraud, threat finance and facilitating organised crime.”, the HSBC case shows that there is no evidence of brand and reputation risks. You have to ask, what is the purpose of such reports?

Professor of Political Science at Oxford University, Pepper Culpepper, acknowledges in the documentary the power banks have in the global system, “You could say, well the banks are getting off a lot lighter than criminals that are individuals and my answer to that is well, of cause, because criminals can’t tear down the system and HSBC can.”. He goes on to comment that the bank was able to signal to a government, “we are a global bank, you are a single government, and so think about the relative power between us”.

And the US government isn’t the only political power that capitulated.

French Investigation of HSBC (2015)#

In February 2015 the Swiss Leaks investigation breaks, alleging that a giant tax evasion scheme was being operated with the knowledge and encouragement of HSBC leadership. Swiss Leaks reported that between 2006 and 2007, €180.6 billion passed through HSBC Private Bank based in Switzerland. The leaked data provided an insight into accounts of over 100,000 clients and 20,000 offshore companies. This data had already been handed to French authorities as early as 2008.

The French National Tax Fraud Investigation Service (DNEF), under then Director Roland Veillepeau, investigated what Veillepeau called, “Something gigantic and contrived, with armies of lawyers, accounting experts [and] consulting firms”. Journalist Gérard Davet of Le Monde, reported on finding everything from, “Drug money, money from terrorism [together with] money from Belgian diamond dealers and French dental surgeons, money of the elite, the world of showbiz, of French and European aristocracy”, concluding it appears to be a “sport, hiding money in Switzerland and at HSBC”.

HSBC Holdings was officially ‘mis en examen’, the French equivalent of being charged, for complicity in hiding fiscal fraud and illegal selling, via its Swiss arm between 2006 and 2007. Veillepeau said “I dream of the day when French judges will issue international arrest warrants against the big bosses of the Swiss banks”. But in the end, there was no lawsuit against HSBC or its leadership team. In 2017, HSBC agreed to pay $352 million to settle charges that it helped wealthy clients of its private Swiss bank evade taxes in France. Veillepeau was dismissed, the scale of this fraud cost him his career.

Swiss Investigation of HSBC (2015)#

In this case even the Swiss government felt like it must take some public action and, on camera, raids the offices of HSBC. But the investigation, led by Olivier Jornot, Attorney General of Geneva lasts just three months before it is closed down; the result is HSBC is fined just €40 million; a slap on the wrist. The maximum fine that can be imposed under Swiss law for money laundering is just 5 million Swiss Francs.

The UK Investigation of HSBC (2015)#

In the UK, HSBC Chief Executive, Stuart Gulliver, and other HSBC executives were summoned before the Treasury’s Public Accounts Committee. The Chair, Margaret Hodge, said to Gulliver, “You got paid through a Panamanian account that had been set up by a man who managed accounts for Assad and Mugabe”. At the time Gulliver had ‘non-dom’ status, having changed his domicile to Hong Kong for tax purposes. The inquiry highlighted he was also one of HSBC’s first Swiss private banking customers, having opened an account 17 years earlier.

The Treasury’s Public Accounts Committee probe led to articles about the bank’s leadership feeling that the questioning was overly aggressive. In the documentary, Hodge makes a telling comment about Treasury’s Public Accounts Committee “this is one of the few times when politics trumps”, continuing, “[governments] are capable of regulating the banks properly – of course we are – do we want to is really the important question”. The implications of these statements are that the norm is that ‘business trumps politics’, and we are living in kleptocracies not democracies.

On the 31 December 2015 the regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), shelved plans for an inquiry into the culture of the British banking system. At the time, Percival Stanion, a top strategist at Pictet Asset Management, told the BBC that it was, “no coincidence” that the FCA had ditched the investigation after HSBC threatened to quit the City of London, complaining of too much regulation!

Banks were left to self-monitor. HSBC stated it recruited 9,000 people tasked with identifying suspicious transaction and reporting these ‘internally’. That’s probably as far as it goes, as it looks like ‘doing something’ without doing anything that would actually reduce profits.

Given how obvious the deception is, the question must be asked, why would conservation NGOs ignore these facts and pretend that asking the banks nicely to do more to identify suspicious transactions from wildlife crime is going to result in any meaningful actions?

The Panama Papers Published (April 2016) #

Within a matter of months of the Swiss Leaks investigations being shelved, the Panama Papers became the breaking scandal globally. The 11.5 million leaked documents detail financial and attorney–client information for more than 214,488 offshore entities.

Will Fitzgibbon, one of the journalists involved in the story said, “No matter where you live, no matter what kind of business you are in, if you wish to enter the offshore system, HSBC is likely to be your bank”. As a result, journalists searched the Panama Papers database for HSBC and found thousands of results – emails, word documents, excel documents discussing HSBC’s role in the offshore system. With the finding Fitzgibbon concludes, “it is interesting that the HSBC bank that you and I know, does seem like a world away from the kind of HSBC whose activities and clients emerge in the Panama Papers.”. One former banker and writer on the industry, Nomi Prins, states in the documentary investigating the bank, “HSBC is considered one of the best money laundering institutions globally”.

Given the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) shelved an inquiry into the culture of the British banking system on the 31st of December 2015, just a few months earlier, maybe in a belated act to save face, Prime Minister David Cameron decided that the UK would host an Anti-Corruption Summit in 2016. But was this inquiry simply more greenwashing? A BBC documentary series provides an insight into how perceptions are managed, as it explores how power really works, comparing reality, ideology and conspiracy. In the concluding episode, one theme explored is, “Why is British business law is so open to corruption? Why is fraud virtually a risk-free crime in Britain?”, with one interviewee concluding, “Because decisions have been made [by the government] on there is so much money coming into London we don’t want to stop it”.

In an interview for another BBC series on money laundering, David Lewis, head of anti-money laundering policy at the UK Treasury between 2009 and 2015 says, “In the whole of that time I was asked only once what could be done to tackle money laundering, but I was repeatedly asked to justify our money laundering regulations and why we need to comply to global standards and what we can do to reduce the burden of those regulations. I was put in star chambers with ministers where I was grilled about why we have these regulations. They were things like the Red Tape Challenge, policy challengers across Whitehall to get rid of regulations. That meant I spent all of my time trying to defend any action at all on money laundering, let alone taking more action”.

As recently as December 2023, in the article, Blink and You Missed It: The UK Government’s New Organised Crime Strategy, Cathy Haenlein the Director of Organised Crime and Policing Studies at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) asks the question “What does it tell us about the current government’s approach to this expanding national security threat?”. Haenlein’s article ponders why, “Most recently, the 2023 National Strategic Assessment judged the threat to have continued to grow in the previous year. Increases were seen in six areas: organised immigration crime; drugs; fraud; modern slavery and human trafficking; money laundering; and organised acquisitive crime. It is surprising that attempts to quantify this sustained growth do not appear to have been made in formulating the new strategy.”

Given ALL this, why do global conservation NGOs waste their time writing reports to “provide advice to financial institutions on risks and characteristics of wildlife and timber trafficking relevant to detecting suspicious transactions”? Why help to perpetuate the illusion that the banking sector is unaware of their role?

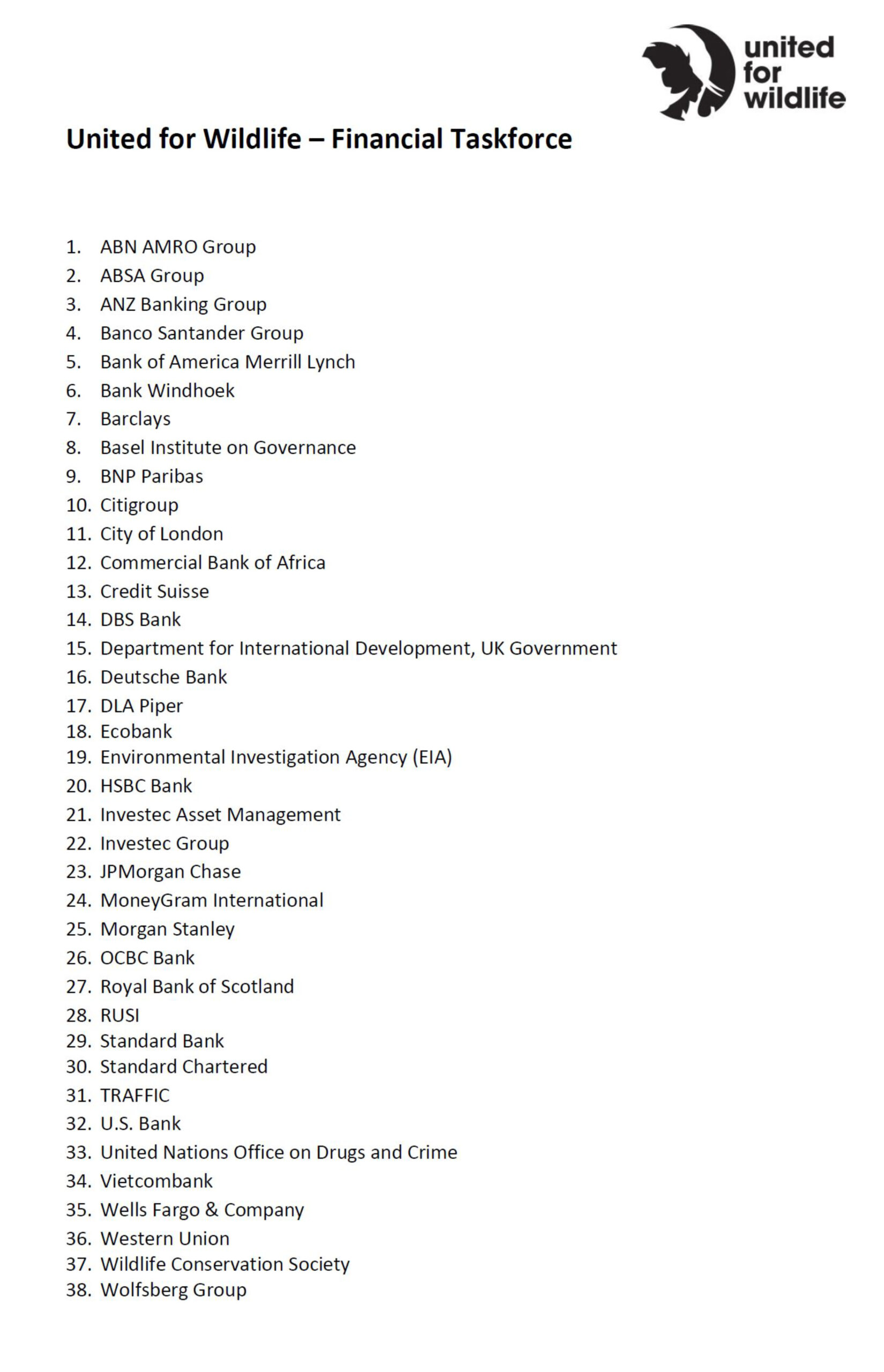

The Tone From The Top#

One reason conservation NGOs may feel they have a licence to perpetuate this illusion is because of the ‘tone from the top’. It is disappointing that Prince William’s conservation charity United for Wildlife, and it’s chairman, former conservative government cabinet minister William Hague, created the Financial Taskforce “to better identify suspicious activity in a bid to disrupt the illegal income generated by wildlife trafficking” and invited HSBC Bank, and a number of other banks who have also been fined because of breaching their anti-money laundering responsibilities, to be a part of the taskforce.

Similarly, it is disappointing that in King Charles’ birthday Honors list, after what happened with Stephan Green, the current chair of HSBC received a knighthood less than 6 months after The Bank of England fined HSBC £57.4 million for failing to protect billions of deposits for hundreds of customers in a “serious” compliance breach that lasted for seven years.

Was this really the time to honour yet another of the bank’s directors? It should be acknowledged that Honours are awarded on the advice of the Cabinet Office, which points to a level of tone deafness of the Steven Green 2010 peerage.

This goes beyond maintaining the status quo, in all likelihood the bank’s lack of action in tackling money laundering will get worse as a result of “the consequences of no consequences”. It goes some way to highlighting why collectively we are not just falling short on the actions needed to address global warming and biodiversity loss but why we are going backwards.

Given the Panama Papers, Swiss Leaks and the US, French, Swiss, and UK investigations no organisation can claim it didn’t know about HSBC’s behaviour. Currently, NGOs enjoy higher levels of public trust than most other institutions, much higher than governments and businesses. Collaborations between conservation NGOs and business can aid businesses to launder their reputations, including the parts they play in the destruction of the natural world.

In approaching John Christensen, Founder of the Tax justice Network for a comment on this issue, he replied, “Steadily, stealthily, the global financial system was reconfigured from the 1950s to serve the interests of a class of untouchable and unaccountable offshore-based malefactors, among whom banks like HSBC played a prominent role. Deploying secretive shell companies to hide their identities, these malefactors have spent hundreds of millions of dollars lobbying politicians to secure weaker environmental protections and reduce the policing required to curtail wildlife trafficking. It is unseemly, to put it mildly, that any NGO committed to conservation should want to play a part in greenwashing the reputations of banks involved in money-laundering the proceeds from crimes against nature. The wholescale looting of natural resources, and the associated laundering of the proceeds to secret offshore bank accounts has increased poverty – because so little of that wealth is invested in new productive activity – while also undermining public confidence in the rule of law. If we seriously want to tackle the criminogenic financial systems that enables so much of the despoliation of the global ecosystem we must take all necessary measures to ensure that the perpetrators of this ecocide can no longer hide their identity behind offshore trusts, shell companies and foundations, while using public trust in NGOs as a fig-leaf to distract from their sordid activities”.

Lina Khan, Chair of the US Federal Trade Commission, is right when she says, “First companies become too big to fail, then too big to jail, then too big to care”. Yet too many policy makers are in denial that companies have been allowed to evolve to the point where they become too big to fail and too big to jail. The lack of action in constraining companies in both size and behaviour creates a system where companies don’t really need to care about even the biggest threats to our collective survival – biodiversity loss and climate change. From the Magnificent 7, to the banking industry and fossil fuels, multinational corporations have rendered governments powerless. Until this is addressed we cannot turn the tide on the unchecked overexploitation of the natural world.

One of the many ways we are collectively not facing up to this inconvenient truth is to believe that ‘capacity building’ in financial institutions is needed to help them identify suspicious transaction linked to wildlife and timber trafficking. It should be obvious to anyone who cares to scratch the surface of money laundering that it happens with the tacit knowledge and the implicit or even explicit support of the banks.

As we approach the CBD CoP16, profit making from predatory business activities must be front of mind, together with the current ease of greenwashing. Conservation NGOs must review their role in the reputation laundromat.