If there is one species that shows CITES doesn’t work in its current form it’s the Siamese Crocodile. These crocodiles were once widespread throughout much of mainland Southeast Asia. From the 1950s commercial hunting for skins and then the collection of animals to stock crocodile farms, again to supply the international skin trade, means the species has disappeared from 99% of its former range.

CITES was set up to protect the likes of the Siamese Crocodile, which has been listed on CITES Appendix I since the convention came into force in 1975. In 1992 the IUCN declared the Siamese Crocodile to be effectively extinct in the wild. It is estimated that there are fewer than 1000 adult individuals surviving in the wild across its historic range, making the Siamese Crocodile one of the world’s rarest reptiles.

In 2021, conservationist squealed with delight when eight Siamese crocodile hatchlings were photographed in the wild in Cambodia. The good news story echoed around the world. This was followed in early 2022, when 25 Siamese crocodiles were released into the wild in Cambodia, with news outlets saying that this raised hope for their conservation as the species was being brought back from the brink.

But all this is a little jarring when you learn that millions of Siamese crocodiles have been legally traded over the years since 1975, even with its CITES Appendix I listing. Having an Appendix I listing should, in theory, mean that the species can’t be traded for commercial purposes. But the convention provides an exemption for captive bred specimens under Article VII, paragraph 4.

What CITES, corporate conservation and the luxury leather industry are NOT talking about is that the massive trade in captive bred Siamese crocodiles has continued unabated for 50 years, since CITES came into force.

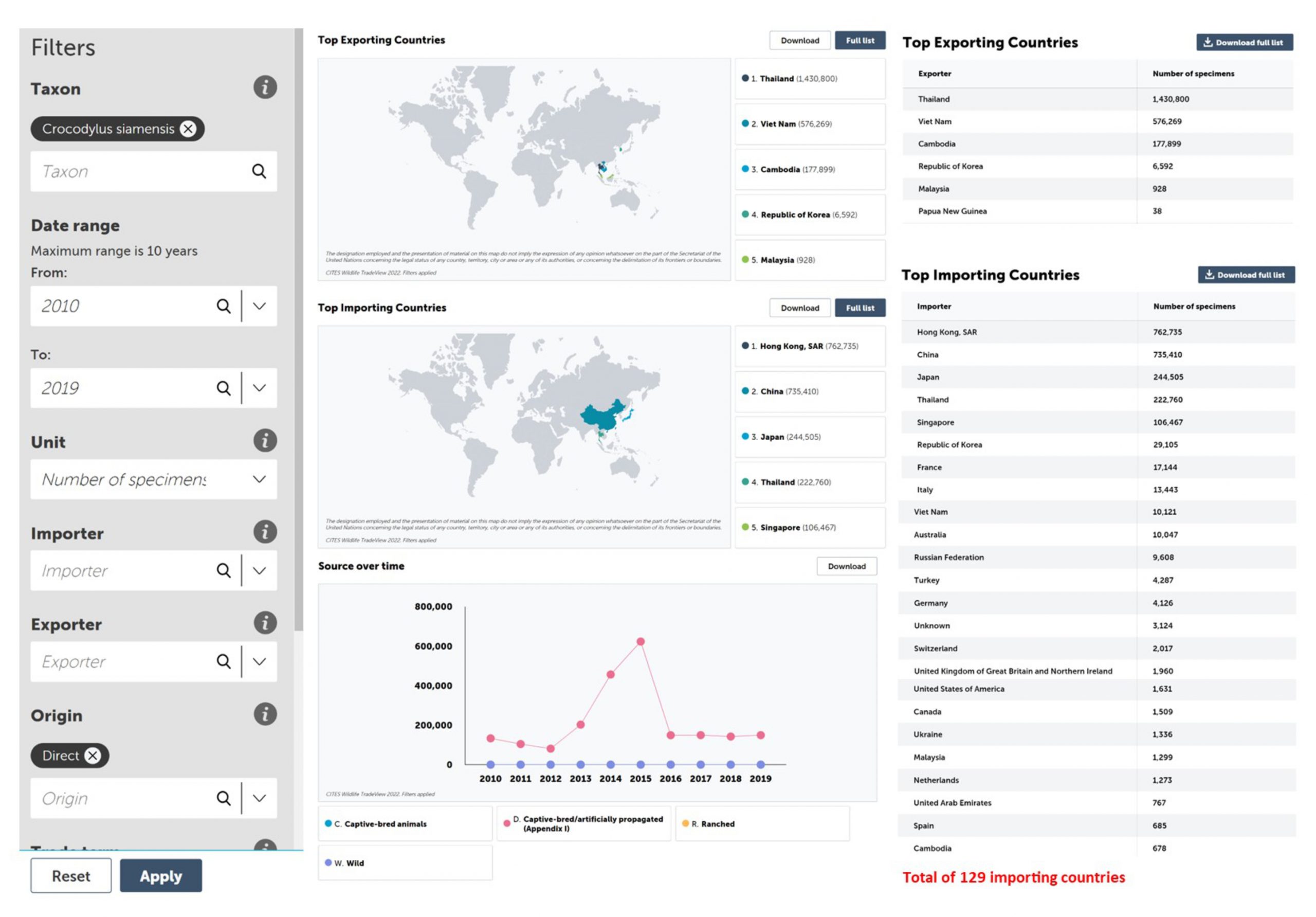

In the years 2010-2019, 1,430,000 were exported from Thailand alone, a country where it is estimated that there are only 200 Siamese crocodiles alive in the wild. A 2013 submission to CITES CoP by Thailand highlights that there are 836 crocodile farms registered with the management authority of Thailand. Among them there are 23 farms registered as a captive breeding operation that breed Appendix I species in captivity for commercial purposes; it doesn’t mention conservation.

Viet Nam is the next biggest exporter with 576,269 and then Cambodia 177,899; for comparison, fewer than 250 mature individuals are thought to be living in the wild in Cambodia.

Source: https://tradeview.cites.org/

This example provides clear evidence that allowing the regulation of the legal trade under the current CITES process has no conservation value and that sustainable use is about sustaining profits and not protecting species from extinction in the wild. The conservation status of the Siamese crocodile has not improved since it was first listed for CITES trade restrictions in 1975, it remains critically endangered according to the IUCN Redlist.

The CITES trade model has had nearly 50 years to reverse the decline of this species in the wild and it has achieved nothing. If ‘sustainable use’ was truly what CITES claims it is about, why has no significant money been redirected from industry profits to re-establishing wild populations? And when funds are made available, why do they come from philanthropists and not industry. The products derived from Siamese crocodile leather are not cheap and contribute to the high profits of luxury brands. Siamese crocodile skin bags, shoes and more can be purchased online with US$1,000+ price tags.

Yet, the crocodile trade is the CITES go-to example for the proponents of ‘sustainable use’, in relation to conservation outcomes and benefits to local communities.

To be clear, their one trick pony example is about the Australian crocodile industry clinically sidestepping the fact that Australia’s GDP per capita is US$52,000 compared to Cambodia’s GDP per capita at US$1,500, Viet Nam’s US$2,800 and Thailand’s US$7,200. Similarly, the fact that the combined population of the three countries is 7-times the Australian population is conveniently ignored.

Also ignored by CITES are the luxury brands frankly meaningless in-house, voluntary certification schemes, which have grown in recent decades as the independent global regulator has been impoverished to the point of being useless. The fact that the CITES regulator provided an exemption for captive bred species under Article VII, paragraph 4, right from the time it came into force, in 1975, is just one example of the loopholes that need to be addressed by a review and the modernisation of the CITES convention. As a reminder the CITES convention has had just one review since it came into force in 1975, that single review happened in 1994.

Any future review must consider the purpose of captive breeding of Appendix I species Article VII, paragraph 4. Why? Because currently CITES makes no stipulation about deriving any conservation or community benefit from such operations. As long as ‘sustainable use’ that benefits wild populations and local communities remains an accidental outcome of trade and CITES processes, rather than formally built into the regulation process, any examples touted by CITES or the IUCN should be seen for what they really are – propaganda to further the ‘sustainable use’ agenda.

Captive breeding of wild animals is big business.

At the start of the pandemic 20,000 captive breeding facilities were closed in China alone and many more in other countries. While this isn’t all about species listed under CITES for trade restrictions, it is important to consider 1) that the legal trade is consuming these species, effectively unmonitored and unregulated, at an alarming rate and 2) it takes on average 12 years for a species to be protected by CITES once that species is identified by the IUCN Red List as being threatened by trade; some species have already been waiting up to 24 years to be listed under CITES after first being identified by the IUCN Red List.

Species are listed on CITES Appendix I only when the wild population is under extreme threat, like the white and black rhinoceros. The exemption under Article VII, paragraph 4 to allow commercial trade in such species can lead to perverse conservation outcomes, as with the Siamese crocodile. Moves by the private rhino owners in South Africa to push for commercial trade of rhino horn under this exemption should be seen for what they are – a simple play to make a profit.

In the same way as the Siamese crocodile was harvested from the wild to stock crocodile farms in the 1950s, rhino farms in South Africa are stocked with animals purchased from the countries national parks. The selling off to private owners was of course done under the banner of ‘conservation’ when poaching reached sky-high levels between 2012 and 2018.

It is hard for the likes of CITES and the IUCN to try to continue to legitimise the ‘sustainable use’ model as a way to conserve wild populations. The landmark May 2019 IPBES report into the global extinction crisis debunked the sustainable use ideology when it confirmed that direct exploitation for trade is the most important driver of decline and extinction risk for marine species and the second most important driver for terrestrial and freshwater species.

To try to maintain support for the sustainable use model, in the face of the growing belief that sustainability is being oversold and mostly greenwashing, CITES and the IUCN have changed the focus to legal trade in endangered species being used for poverty alleviation in communities living next to key wildlife populations.

Focusing on minuscule payments to local communities in a handful of cases clinically sidesteps the fact that globally it is conservatively estimated that over US$1 Trillion in capital flight and tax evasion flows out of developing countries every year to secrecy jurisdictions worldwide.

Without modernising CITES this situation is not going to change and we will continue to legally sellout wildlife and the natural world.