In the years I have been researching the live trade in wild species, with a particular focus on the species listed by the CITES convention, what constantly amazes me is how obviously the system is flawed and yet how little action or apparent interest there is in seeing this improved. Our most important treaty governing trade in wild species is neglected to the point it is rendered unfit for purpose.

Over this time, I have read numerous accounts of high mortality rates in supply chains, welfare issues that must cause unimaginable levels of stress and suffering, spread of disease to other animals and humans as well as potential biosecurity risks. There is no doubt that the legal trade in wild species is a system which in many instances is failing to achieve the outcomes we might hope it would achieve. From my veterinary perspective the adverse events that are occurring over these supply chains call for the CITES own Morbidity and Mortality Review (MMR).

In medicine and increasingly in veterinary medicine, the use of Morbidity and Mortality Reviews are commonplace. Key to the process of an MMR is the principle of “no blame.” It is the process and events that are scrutinised and questioned and not the individuals involved. In my view the only time blame should be directed is when there is recognition that failure/poor outcomes have occurred and no reflection occurs to see a change of procedure/protocol to minimise the chance of the same outcome occurring again. The definition of insanity is doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different outcome – or words to that effect.

As a veterinarian of more than 30 years my question is, is there something for conservation to learn from the MMR process and could the principles of MMRs be used in the conservation sector to ask honest questions and seek better outcomes?

I believe the answer is a resounding YES and I’m calling ALL vets to join me in supporting a review of CITES to see better outcomes for animals traded live.

What is an MMR?#

A well-constructed and run MMR is a valuable concept. Used appropriately it has significant benefits. A literature review from 2017 concluded, “MMRs decrease gross mortality rates and are effective in identifying and engaging clinicians in system improvements”. The review process looks at an outcome and steps back to consider how that outcome eventuated. I was taught to ask “why” five times. We’ve had this outcome, why? That happened because? That was as a result of what? What triggered the “what”? The trigger occurred when? Essentially the concept looks at the pathway of events leading to an outcome. It aims to identify key points where the procedures and protocols can be improved to decrease the potential that the same decisions/triggers do not occur again to diminish the chance of the same negative outcome. The process recognises failure, questions the status quo and asks how can that process be done better in the future.

With regard MMRs, there is a need to have the review within a reasonable time frame after the event and involve sufficient people with expertise in the area and those involved with the event being reviewed. Key to the success of the review is a recognition that a poor outcome has occurred, that deep questioning is undertaken of the events leading up to the poor outcome occurs and that a no blame culture pervades the process such that information is shared freely and egos need not be dented. It is not a process to seek recriminations. It is a chance for an acknowledgment that procedures and systems can fail and an opportunity to investigate that failure collaboratively without fear of persecution to find ways of improving the status quo of operations.

It’s a simple concept really. Create a blame free environment for a group of relevant people who accept and recognize the failure of a system, that the status quo is unacceptable, delve deeply into at what points the system has failed and put in place actions that diminish the risk that these tripping points occur again. It is not a process of throwing out an entire system but rather a mechanism to evolve an existing system. The reviews are not designed to discard what exists but accept that everything can be done better and that improvement can be achieved with gradual evolution. I can’t see too many negatives to that, can you?

How do I see MMRs fitting Conservation?#

So, if the concept is good enough to be used in the case of life and death scenarios involving human health and survival outcomes, why are the principles not suitable in other spheres, let’s say conservation? The landmark IPBES report of 2019, suggests we have a MILLION life and death reasons to consider an MMR into conservation. According to this report, “direct exploitation” (read trade) is the single largest threat to marine species and the second biggest, behind habitat destruction, to terrestrial and freshwater species.

I would ask the following questions –

Q. What’s the world’s most significant treaty established for the monitoring of trade in wild species and intended to protect them from over exploitation?

A. The Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

Q. If trade is now the biggest or second biggest driver that threatens species loss globally, does this suggest that CITES can claim to have protected the over exploitation of the living world since its inception in 1975?

A. No. At best we can argue that the biodiversity crisis might be worse without it but leading into the 50-year celebrations of its adoption then CITES itself and Conservation groups must be careful in glossing over its sizeable failure as well.

Q. Do we recognise a problem with CITES?

A. Yes and No – it seems too many leaders in conservation do not recognise this as I can’t believe the system would be as it is now 50 years after its inception if this was so. However, the CITES Secretariat statement released in the COP 20 (CoP20 Doc. 14) documentation publicly acknowledges that the system cannot cope and is failing.

The second statement of major concern has amazingly received almost no coverage either. This statement from CITES document CoP20 Doc. 7.1 predicts a possible, “loss of up to 22 percent of the core budget of the Secretariat.” Unable to cope with the scope of work required and with a potential funding crisis. Surely, it is time for the Conservation sector to acknowledge the state of play and be pushing for an overhaul of CITES. CITES has not had a strategic review since 1994!

Q. If CITES is failing, should we then abandon the sinking ship to float in a flotilla of tiny life rafts paddling our own courses in the hope of landing on the shores of the promised land?

A. NO – I believe we should acknowledge we have a leaking hull, accept that our stewardship has resulted in us hitting the outer reef, come together in an environment of no blame to assess what steps need to be taken to address our immediate problem and how in future we can chart a course using the instruments we have available at this time to maximise the chance that we avoid the next reef on our expedition. In time new tools and instruments will become available to aid us, maybe we will build a better ship altogether, but it’s fair to say that the chances of a Shackleton like escape is unlikely if we all take to our lifeboats and take our chances alone.

Q. So if our management of CITES has resulted in a near death event for it, is it time an MMR was done?

A. – YES. Taking the principles of the MMR then it seems logical to accept the first point. CITES is no longer fit for purpose, which even the Secretariat is now willing to admit publicly. If conservation groups will finally admit that, then we must take a no blame approach that we have reached this point under their watch and instead look at what has been overlooked by those in conservation for so long that has allowed us to reach this crisis in the life of CITES. This is more than a health scare, this is a near death moment.

Why should vets care?#

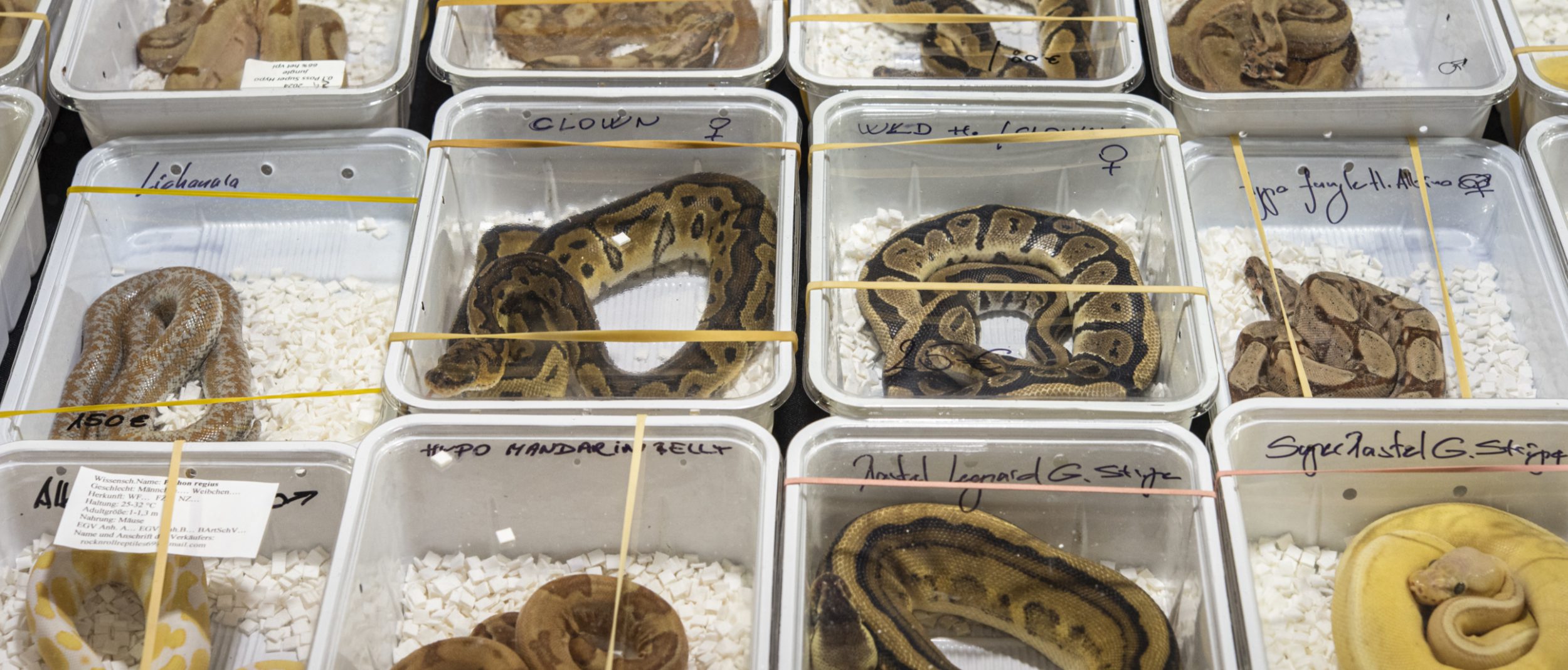

From a veterinary profession point of view the poor management of the LEGAL trade in live species is resulting in poor welfare outcomes for individual animals, biosecurity risks, zoonotic disease risks and on a larger scale, biodiversity loss concerns. This biodiversity loss concern is through both unsustainable levels of consumption and in acting as an umbrella for illegal trade. As I have previously written, it is time for us as a profession to step outside our one-on-one mentality of health care and drive for better outcomes for species, not just individuals. I’m not accusing vets of not being interested in animal welfare in relation to their own patients, but I believe as a profession we are turning a blind eye to poor welfare outcomes for a silent mass that we should be acting as advocates for.

The time is right for the profession to call for, and play an active role in, an MMR like strategic review of CITES. Imagine if as a profession we had recognised the failure of our clinical procedures and patient outcomes dating back to1994 and sat on our hands doing things the same way. If we’d not recognised failure in our clinics and not changed the status quo of operation I think we would have been classified as negligent. Why then do we accept a lack of review of a system as important as CITES after more than 30 years?

In the 1980’s there were less than a 1000 species listed with CITES. There is now more than 40,000! As mentioned earlier the CITES Secretariat has finally admitted the system cannot cope. With the problem acknowledged and an approach that places no blame for how we arrived at that point then we must ask our 5 questions on how we got here. At this point we have identified the problem as we have too many species listed on CITES to manage them all appropriately. The Secretariat’s solution appears to be to say we will prioritise key species. In medical terms this is akin to saying, we will only treat the famous people as we will receive less criticism for neglecting the dying unknowns. I would think instead we should be acknowledging our system is failing, identifying where this is happening and looking to intervene such that the system is more resilient and likely to help all patients and not just those that have the highest number of Followers.

CITES is overwhelmed by its own admission – what now?#

Our identified problem then is, we have too many species to adequately manage on CITES. Following my 5 question rule to look behind this we might ask–

1. Why are so many species listed? Because too many species are being exploited through trade and loss of habitat at levels that are unsustainable.

2. How can the trade levels be unsustainable when we have CITES? Because we have a poor understanding of the true volume of trade and are making decisions based on non-granular data.

3. Why have we got poor data? Because we are operating on a paper based permitting system that is open to fraudulent use and doesn’t allow for end-to-end traceability of trade.

4. Why are we operating with outdated technology? Because we have insufficient funds available to CITES to implement this and the necessary compliance and enforcement measures needed to administer it.

5. Why do we have insufficient funds available? Because we haven’t created a user pays system that can fund a modern permitting system, compliance and enforcement needs and see funds directed back to exporting countries to ensure sustainability is fact, not an ideology.

As a veterinary surgeon I feel it’s time that the principles of MMRs stand as a wonderful example of how we could consider the issue of a CITES system in crisis. Not discard the concept of CITES and not just say, the procedure is good, but we will only use it on a lucky few as the Secretariat has suggested. An honest, no blame review of why the process is not working as well as it should for as many as it should is required. Asking the questions to identify at what points the system is failing and then enacting the change to remove these stumbling blocks would seem a logical approach.

CITES needs a Strategic Review. The veterinary profession has so many reasons to understand why and to see the benefits that would transpire from this in multiple areas that vets play a role.

I ask that as individuals we push our professional bodies to bring influence where needed to see this urgently necessary review done. CITES is in a critical condition, but as a profession we have the skills to resuscitate it to be the entity it was intended to be.