When you add up everything that is being spent to save the rhino from extinction in the wild, then it would become a teeny tiny fraction of 1%. The vast majority of the money donated to rhino conservation is spent on the ground on protection measures – fencing, rangers, equipment, dehorning etc. Only a relatively small percentage is spent in demand countries. Of that percentage, again only a small fraction goes into what can be classed as demand reduction campaigns.

Breaking The Brand Basic Definitions

As an introduction to this blog, I must qualify Breaking The Brand’s definition of what constitutes a demand reduction campaign: It is a campaign that elicits an emotional response in the current user groups to such a level that it triggers them to stop using rhino horn in a time frame that is useful to save the rhino from extinction in the wild. The header diagram summarizes our definition of 4 types of campaigns, namely:

- Awareness Raising

- Education

- Belief Challenging

- Demand Reduction (Behaviour Change)

Why is this definition critical? There are several reasons, but for the sake of this blog, I will stick to three.

- Ammunition for pro-trade lobby

As discussed in a previous blog from January 2015, Poor Quality Demand Reduction Campaigns and Strategies Will Provide Ammunition for Pro-Trade Lobby Groups, one of the final things to stand in the way of the pro-trade lobby is a successful demand reduction approach to stop rhino poaching. A perfect example of the pro-trade groups strategy is seen in a news segment outlining an integrated rhino anti-poaching strategy dubbed “The Plan” (1st October 2015, Cape Town). Pelham Jones, chairman of the Private Rhino Owners Association (PROA) and pro-trade stated “Despite billions being spent on an annual basis to collapse the illegal demand, it is not working.” Statements such as this have been a constant from the pro-trade people over the last year or so. I found no evidence of the large conservation groups challenging such a ridiculous statement of billions being spent. - Timing of CITES Meeting

If parties go to the 2016 CITES meeting saying $xx million have been spent on demand reduction and poaching hasn’t been significantly reduced, this will play into the hands of those wishing to legalise trade (“protection and demand reduction have not worked, the ONLY thing left to try to save the rhino is to legalise trade NOW”). If such statements are not challenged, because of the poor understanding what demand reduction is, we are running the risk of getting the wrong outcome. This may not affect the 2016 CITES meeting outcome, but, as many think, if it is left as a “let’s wait and see” for 2019 this indecision will be disastrous for the rhino. - Donor expectations

In the last couple of years no doubt campaigns have been pitched to potential donors as ‘demand reduction/behaviour change’ campaigns. Donations have been made on the basis of supporting projects specifically targeting the users with an expectation of a change in behaviour. Donors will now be asking about the results. It will be hard for organisations to admit that their campaigns aren’t working quickly because they aren’t actually behaviour change campaigns, although they were labelled as such. The default position is to say that it will take time to change entrenched user behaviour.

As a result, we decided to apply BTBs definitions to the campaigns that have been rolled out over the last couple of years. Similarly, we have tried to estimate what has been spent on each type of campaign, based on annual reports, other public documents and statements in the press.

User Motivations To Stop Using Rhino Horn

In addition to clarifying the Breaking The Brand definition of what constitutes a demand reduction campaign, we must also re-clarify that to affect demand a campaign MUST trigger a reason to stop using rhino horn. Our interviews with the primary users starting in 2013 highlighted that there are, in reality, only 3 motivators to stop using:

- If using rhino horn negatively impacts my health or the health of someone important to me (family, someone I am wanting to impress etc)

- If using rhino horn has a negative impact on my personal status as a result of using/giving as gift

- If stopping using rhino horn enables my entry to a higher status group

So when you see a campaign, ask yourself, “Would this advert cause health anxiety, status anxiety in the primary users or would it enable them entry to a higher status group if they give up rhino horn?” Only if the answer is yes, is the campaign a demand reduction from BTBs perspective.

We also want to highlight that adverts in one of our campaigns tested the users’ response to the human costs of wildlife poaching. This didn’t emerge from the user interviews as a clear pattern to stop using rhino horn, as the three outlined above did. But we did find in ongoing conversations with our target group we were hearing an increasing sense of ‘shame’ as we discussed the human toll of the poaching crisis. People were not empathetic to the death of rangers, the view being, “They chose to do that job, they could work somewhere else”, but emotion was triggered when BTB discussed the families. Talking about wives becoming widows and children fatherless generated reactions and questions so we decided to add this to the message. So we acknowledge, not all of our adverts can be defined as demand reduction by our criteria, which we highlight in the following analysis.

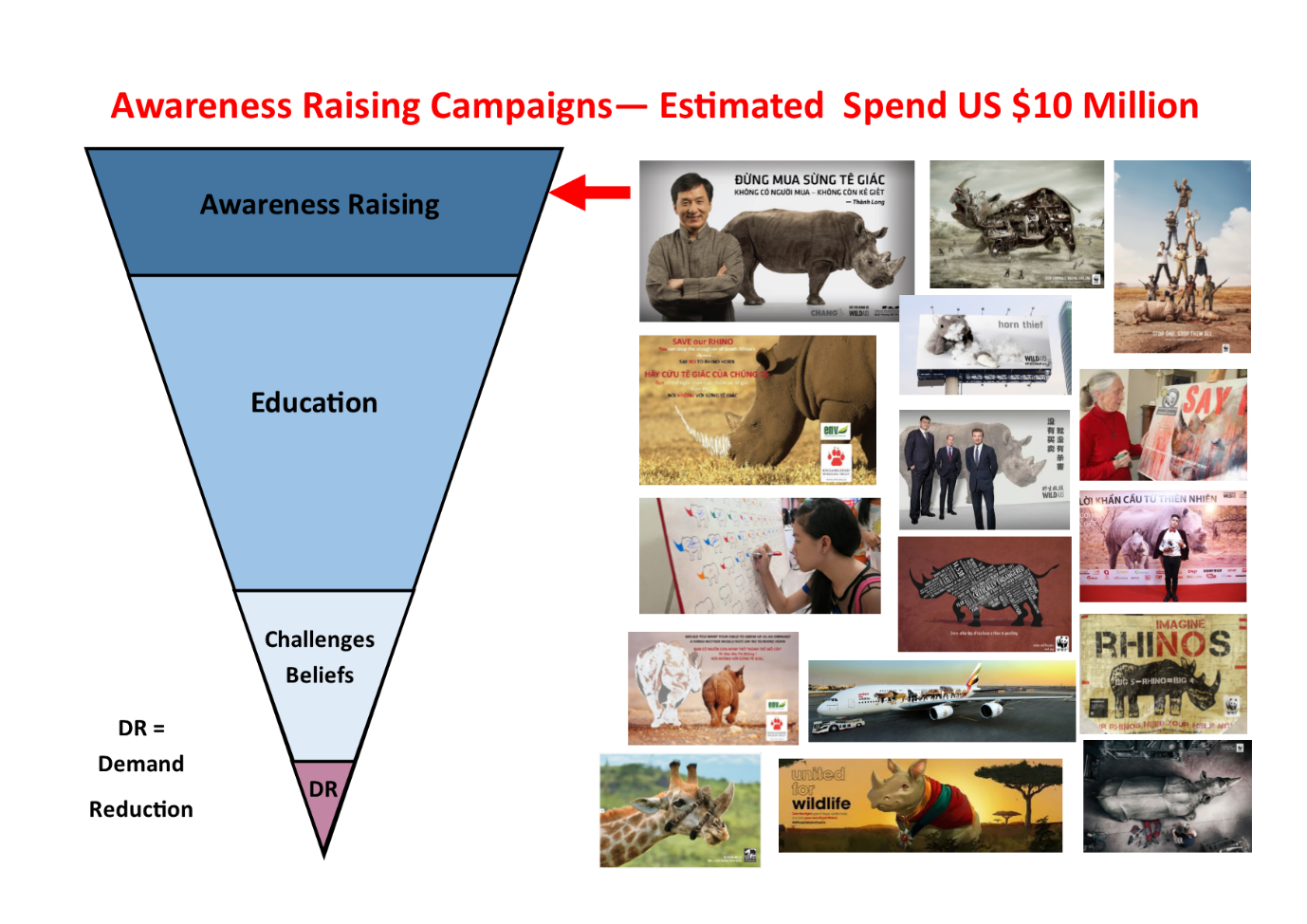

Awareness-Raising Campaigns

The diagram below summarises the campaigns in Viet Nam that we would class under ‘awareness raising’. As you can see from the images these are predominantly campaigns featuring the animal itself that were mostly run in generic public spaces.

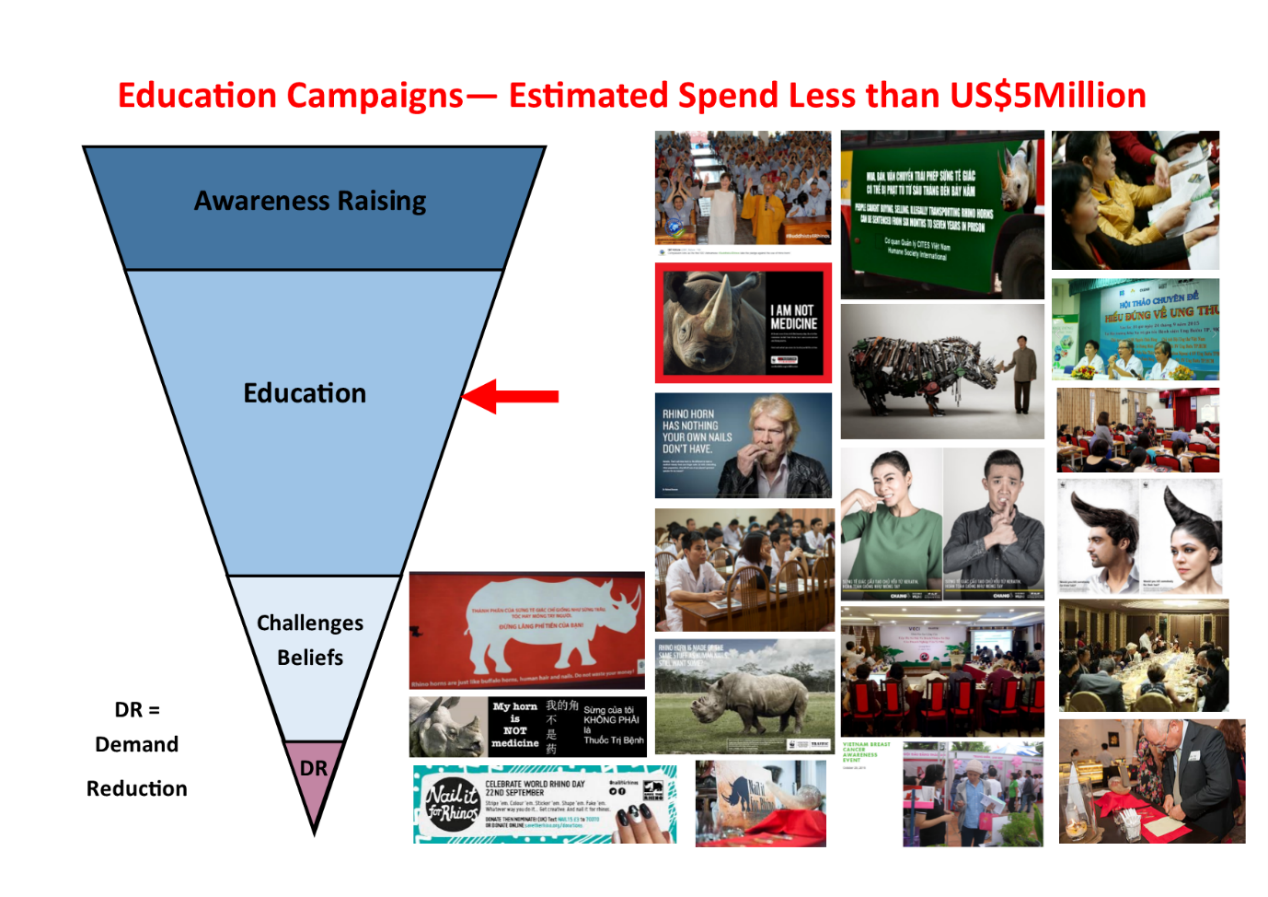

Education Campaigns

These campaigns were more targeted and run in locations / media that could either reach the target group directly or reach people who may influence the target group over the long term (such as their children, traditional medicine practitioners, mainstream doctors etc). There is less focus on the animal and more focus on some educational information, such as:

- The lack of medical benefits of consuming rhino horn

- That rhino horn is like human finger nails/hair

The reason these cannot be classed as ‘Challenging Beliefs’ campaigns is that the Traditional Medicine market for rhino horn is supplying mainly fake horn and currently the consumers of genuine horn do not care about the medical benefits. In addition, we must confirm when we asked the users of rhino horn about the fact that rhino horn was considered the same as human finger nails etc., they said they had heard this for years and the message wasn’t of interest to them. Their use was for symbolic purposes; even if they do ingest horn, they do so in the so called ‘Millionaires Detox Drink’ and this is a status symbol.

This has been confirmed to me to by other groups active in Viet Nam who said their data indicated that messages on chewing nails actually come across as insulting and condescending with the user group.

The campaigns to raise-awareness/educate may eventually ensure younger people don’t become the next generation of rhino horn users. Unfortunately, the key group (Vietnamese businessmen) driving the poaching aren’t interested in media celebrities or educational messages. Just a few days after launching its US$1.6Million campaign WildAid/ChangE admit this themselves: From the article: “Chau said her campaign is finding it “very hard” to convince the public of its current message, that rhino horn has the medical efficacy of fingernails. And while it is having some success raising awareness among young people, it is failing to reach its targeted audience of Vietnam’s top CEOs, wealthy middle aged, and super rich”.

So while it is good that money is being spent on education, but it can’t be confused with user-focused demand reduction campaigns.

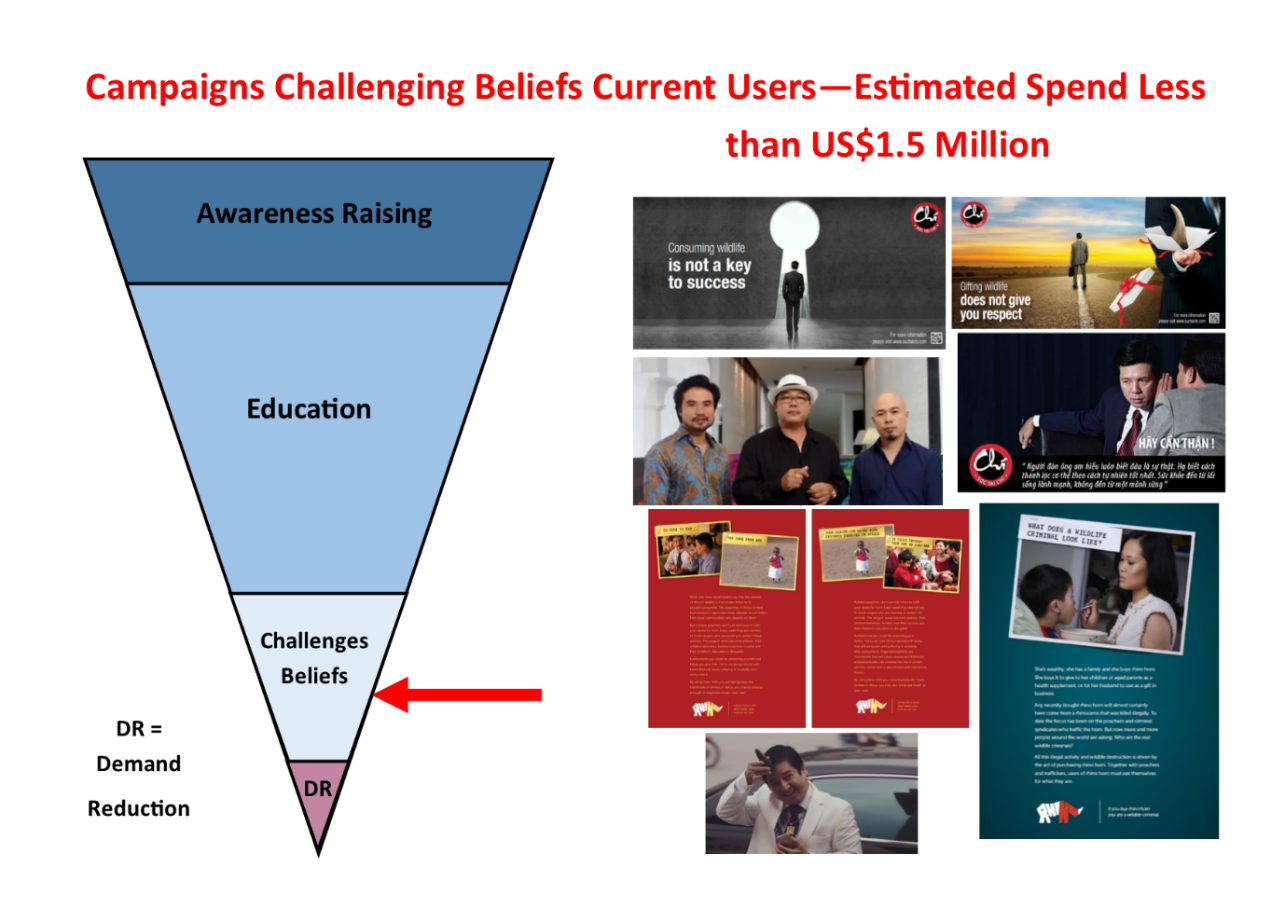

Challenging Beliefs

Now that we come to the pointy end of the inverted pyramid, there are far fewer campaigns and much less money being spent. From our perspective only the TRAFFIC ‘Chi’ campaign, ENV’s ‘taking the micky out of the users’ campaign and some of our ads directly challenge the beliefs of the users and in a way that the users can relate to.

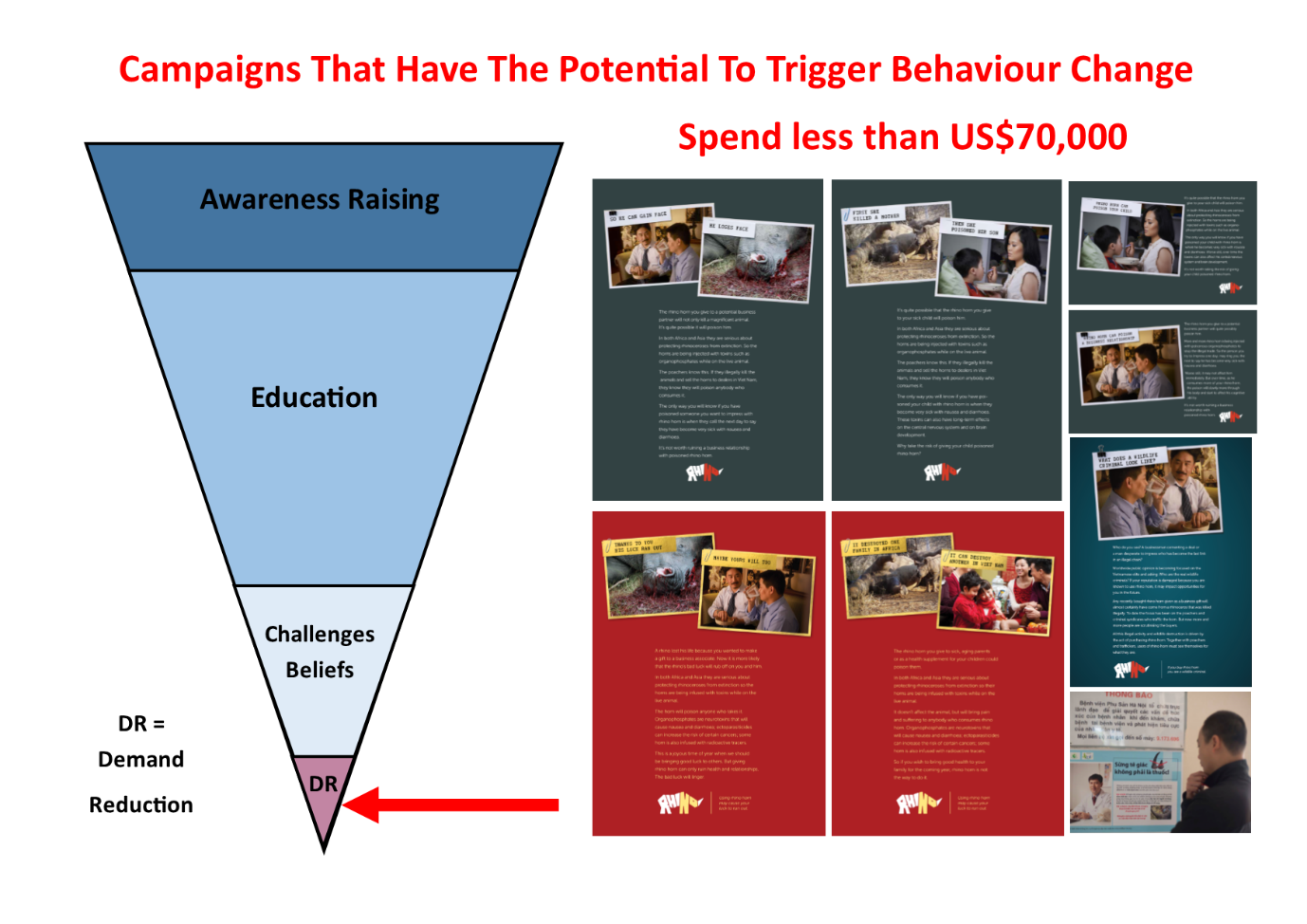

Demand Reduction

Finally, we are down to the only campaigns that can be classed as demand reduction – they trigger an emotion related to one of the motivations to stop in the primary user groups and are targeted directly at those primary user groups. Our campaigns have used both health and status anxiety and WildAct have used health anxiety in their hospital based campaigns. All up, the spend has been less than USD $70,000.

Well Targeted ‘True’ Demand Reduction Campaigns That Are Well Funded

Of course we are not saying that awareness raising and education campaigns are not part of the mix or a waste of money. They are definitely needed to make behaviour change sustainable in the long term and educate potential future consumers in different ways to prevent uptake of use. Yet the problem remains that most of the money for ‘demand reduction’ has actually gone into awareness raising or education. Not through malicious intent, but mainly through ignorance about how to design a demand reduction campaign and fear of alienating donors in the West.

At the same time large donors (mainly governments) have been asking for and provide big donations specifically for demand reduction campaigns, assuming that conservation organisations would go out and seek expert input in designing the right type of campaigns. Given that is not what happened, these organisations are now in a bind to ‘mis-label’ their awareness raising and education campaigns as ‘demand reduction’ so that they can report to their major donors that they have fulfilled the terms of the donation.

This game of mutual deception and ignorance will not stop until donors educate themselves what it really means to design a demand reduction campaign and learn from the sectors that have the background and track record in this area (anti-smoking, anti-alcohol and road safety campaigns).

2015 Poaching Levels

Despite all this, there may have been a small downward shift in rhino poaching levels in South Africa last year, so maybe I am way off the mark and these campaigns actually worked? There are a number of observations that have to be made to address this valid question.

While these campaigns have been running, the full force of the money spend on on-the-ground protection in the last couple of years has been huge, with one, single donation of US$30million going to Kruger National Park alone over this time.

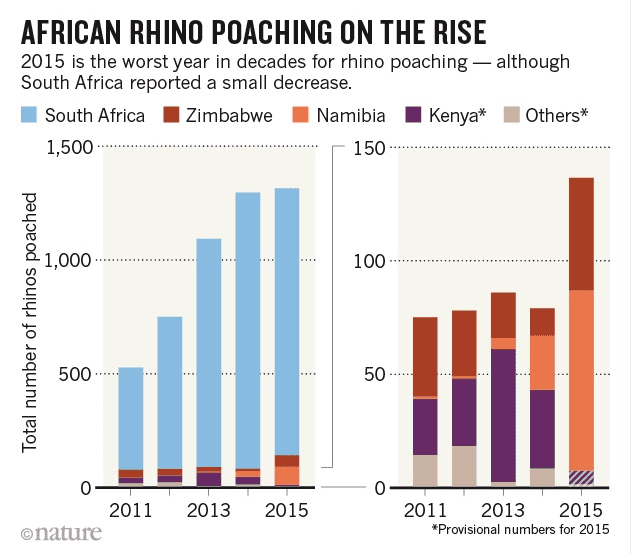

Second, demand is still growing. Whilst South Africa shows basically an unchanged level of poaching between 2014 and 2015, Namibia and Zimbabwe have gone up drastically, taking the total back to 5% growth in poaching year-on-year.

Third, the most important shift in 2015 has been in financial flows into emerging markets such as Viet Nam that have received huge amounts of foreign investment since 2008. The slow-down and volatility in China have led to reversals in these financial flows, primarily affecting Brazil and Russia, but also Indonesia, Viet Nam and the Philippines. Much of these money flows inevitably go directly to the wealthy elite, so when the money dries up, so does their wealth and their ability to buy rhino horn.

Reality Check

The question of demand reduction for rhino horn in Viet Nam will never be answered through running controlled scientific experiments like it is possible in anti-smoking campaigns. The reality remains that only a tiny amount of money has been spent on demand reduction campaigns, compared to anti-poaching measures and awareness-raising / education campaigns. Let’s not keep providing the pro-trade lobby more ammunition to say that demand reduction hasn’t worked, in all honesty rhino horn demand reduction/behaviour change campaigns of the reach, intensity and frequency required to change the primary users behaviour haven’t really started yet…

These are the views of the author: Dr. Lynn Johnson, Founder, Breaking the Brand