Photo by Rafael Ishkhanyan on Unsplash

The CITES, which came into force in July 1975, was born out of a set of assumptions and a geopolitical prospective that reflect the 1960s. As the world changed drastically from the late 1970s CITES didn’t, the articles of the convention have stayed the same. CITES has had only one strategic review in its 50-year history, back in 1994, which also didn’t result in any significant changes. This lack of evolution goes someway to explaining how ineffective the convention is today. Key to the staggering inertia is that the mindset of the academics, NGOs and IGOs, who could have lobbied the convention’s government signatories to evolve with a changing world, are also stuck.

Many are like the theologians who maintained that a moving Earth and a stationary sun were in conflict with the interpretation of scripture, adopted as the Catholic Church’s orthodoxy, and rejected the Copernican model of the solar system. Galileo, who was aligned with Copernicus, was tried by the inquisition for these beliefs, Copernicus having died before the inquisition could get to him!

Conservationists maintain their belief in the currently unprovable sustainable use model with an almost Ptolemaic system orthodoxy; the Earth is stationary and at the centre of the universe. Just as with the solar system, ever more convoluted ‘epicycles’ are required to keep pretending the system is working. Copernicus, Galileo and others simply looked up to the stars to confirm that the Earth moved around the Sun. Why is it that conservationists can’t look at their own data and conclude the obvious; the CITES has failed in its stated primary objective of protecting endangered species from overexploitation, by allowing said species to be traded. It needs to be modernised.

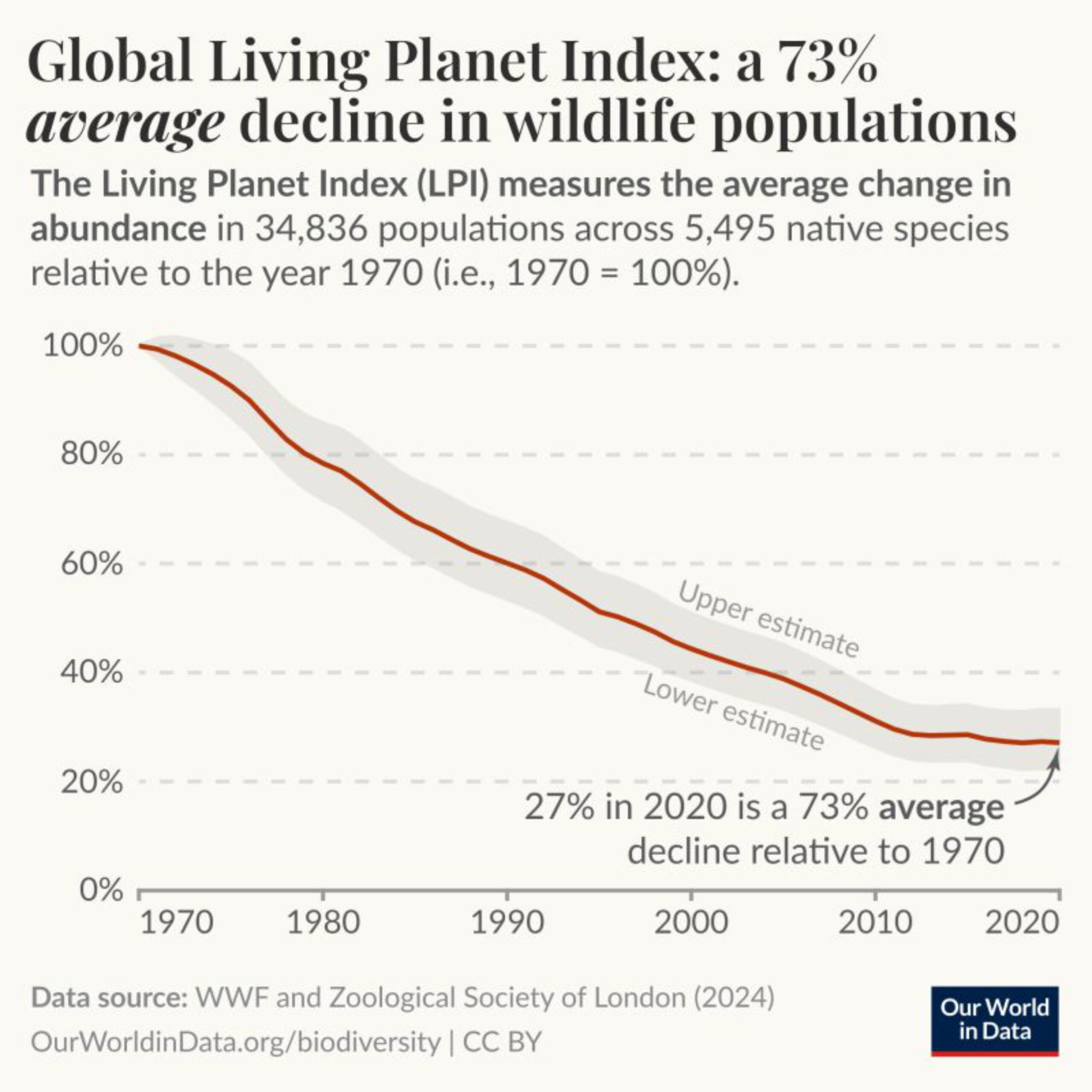

Is it really as easy as looking up to see that CITES isn’t effective? Here is a big hint: The Global Living Planet Index wouldn’t look like this if the CITES had worked!

To accept this fact, too many conservationists would have to admit over this period, when they have had professional skin in the game, they have either missed or ignored key culprits that have driven biodiversity loss, namely unregulated and poorly regulated legal trade, including for the species supposedly regulated by the CITES.

But you don’t have to go back a few hundred years to understand how people and systems get stuck in a mindset. A great current example in why there has been no success in tackling how the commercialisation of wild species is driving biodiversity loss is explained in the parallel wicked problem of “why don’t economists talk about wealth inequality?”, as explained by Gary Stevenson.

Stevenson studied economics and mathematics at the London School of Economics and Oxford. He became a millionaire as a financial trader at Citibank, before he went on to launch a YouTube-channel GarysEconomics, where he campaigns against wealth inequality.

Economists don’t talk about inequality because of the way the subject is taught at university.

They don’t explore questions such as why is housing unaffordable, why are real wages and living standards falling and why have cities become too expensive. The big economic problems of our time are basically not discussed at university.

Instead, to get a job and get published economists have to follow the doctrines of neoclassical economics. This involves a heavily mathematical focus on a ‘model economy’ to observe how changing one thing effects another. For example, if interest rates are cut what does that do to GDP? If people spend less money, what does that do to inflation? If the government raises taxes how does that effect the (model) economy?

But to do this, the model economy is so simplified that it only has one person in the model – one average, representative person – so there is no possibility to look at inequality in the economic models taught at universities. The model looks at one average, ‘representative’ person, or aggregates such as GDP, inflation, unemployment rates, central bank interest rates, level of government spending and taxation. It doesn’t look at distributions, so you can’t have inequality. That’s convenient, right?

Next consider that, if you want to be an influential economist in the world of government policy or academia, then by the time you have a chance to gain this status you have been studying these models for at least 10 years, and probably more. So, you have spent more than a decade learning a model in detail that doesn’t incorporate distribution such as inequality. As Stevenson put it in GarysEconomics, “This is a really effective way to subconsciously convince a person that inequality doesn’t matter”.

When you’re questioned about what is going wrong with the economy, you go back to what you know, are interest rates too high, is government taxation too high, is government spending too low. You want to find answers in the model that you have spend 10-15 years learning, and working within, in detail.

Then one day someone says, I have been looking at the patterns on the streets (I have looking at how the stars travel across the sky) and maybe the problem is inequality, what do you think?

But inequality isn’t in the model that you have invested years of your life in and that your job depends on; how vulnerable would that make you feel when you have 10–20 years or more of professional skin in the game? You double down on what you believe in. It can’t be inequality, because have I spend years looking at interest rates, taxation, government spending, GDP etc and I’m a respected economist (I have status).

If the problem was that growing inequality was making the economy worse, then you wouldn’t have spent years studying something that has nothing to say on this issue, would you? If the public catch on that you have missed the point, then you are professionally buggered. But thankfully, everyone in the professional network (who some call the small conference elite) are in the same boat because they have all studied the same models.

As the real world gets more unequal all you have to do is collude to keep the focus on averages and aggregates. The group doesn’t what to discuss inequality, so it is simply never discussed. This works because it doesn’t undermine what governments, businesses and wealthy investors want, namely more growth and more inequality.

This exact same mechanisms are at work in modern conservation. Conservation academics and NGOs don’t understand business behaviour and power inequalities, or if they do, they ignore them and exclude them from their analysis. They publish thousands of studies on biology, individual species and ecosystems, poaching and wildlife crime and ignore the root causes of biodiversity decline – legal trade.

Conservation studies this…

And, needs to understand this…

In the coming weeks and months, the conference elite will try to create the illusion that CITES trade system has worked and yet all the evidence shows it hasn’t. They will have their go to statements of, “Well I can’t imagine how bad it would have been if we hadn’t had the CITES”; a mindset that has sold out wild species over the last 5 decades, and particularly the last 20 years.

How has this happened? In the same way that economists have ignored inequality in their models of the world, conservationist have ignored business behaviour under capitalism and the universal desire for wealth accumulation.

If they want to save the little that is left, then I would suggest that no matter what species they research, no matter what country they investigate, they all look up.

In looking up they should turn their attention to late stage capitalism, and in doing so, challenge and close down:

- Shareholder primacy, which didn’t really enter business boardrooms until the 1970s. Because capitalists were making plenty of money before shareholder primacy became the accepted model.

- Limited Liability, which in a modern sense only became a uniform attribute of all corporations in the 20th century. As those who have dived into the Limited Liability business structure remind us, “corporations, stock markets and the corporate economy enjoyed a long and prosperous history well before limited liability in its modern sense became established and dominant”

- Secrecy Jurisdictions, Shell Companies and Corporate Tax havens, which again only really took off after WWII, because capitalists were making money before this. Today they represent a mega pool of unproductive money in a world that needs funds to tackle multiple existential crises, including biodiversity loss and climate change.

To those who plan to celebrate CITES 50 years of coming into force, I say biodiversity loss will not be arrested if you don’t turn your attention to overcoming fundamental problems, such as shareholder primacy, limited liability and corporate power etc. Not as much fun as looking at elephants, lions, sharks, oceans, Africa and the Amazon, I know.

As we approach the CITES CoP20, profit making from predatory business activities must be front of mind, together with the current ease of greenwashing. Conservation NGOs must review their role in the reputation laundromat.

The question is, will you maintain the status quo because of your years of ‘skin in the game’. Let’s face it, you probably will because no one is pressuring you to change your model of the world, and you appear to want to keep your job/grants more than you want to really deal with the biodiversity crisis.

But also, let’s be honest, if you don’t change, the situation for the species you say you care about will just get worse and worse.

Will you follow the needs of your funding master’s and stick to Ptolemaic orthodoxy, that the earth stands still, when the species who need you to ensure their survival want you to ‘look up’ and have the courage of Copernicus and Galileo.