In 1871, Ferdinand V. Hayden published the Hayden Geological Survey of the region that would become Yellowstone National Park. He warned that if the park wasn’t created, there were those who would come and “make merchandise of [its] beautiful specimens”, continuing, “the vandals who are now waiting to enter into this wonder-land, will in a single season despoil, beyond recovery, these remarkable curiosities”. While Yellowstone National Park was indeed created in 1872, other regions of the USA and the world weren’t so lucky.

The 15th edition of WWF’s Living Planet Report confirms a catastrophic 73% decline in the global average size of monitored wildlife populations over just 50 years (1970-2020); Latin America and the Caribbean, have recorded a staggering 95% average decline.

These shameful statistics confirm that Hayden’s ‘vandals’ have been allowed to succeed.

Yellowstone National Park was created under President Ulysses S. Grant. As Ian Tyrell explains, conservation during this period of US history and into the early twentieth century, “did not mean preservation alone (or even mainly). It meant efficient use of resources in the interests of both national strength and long term ‘habitability’ for humans”.

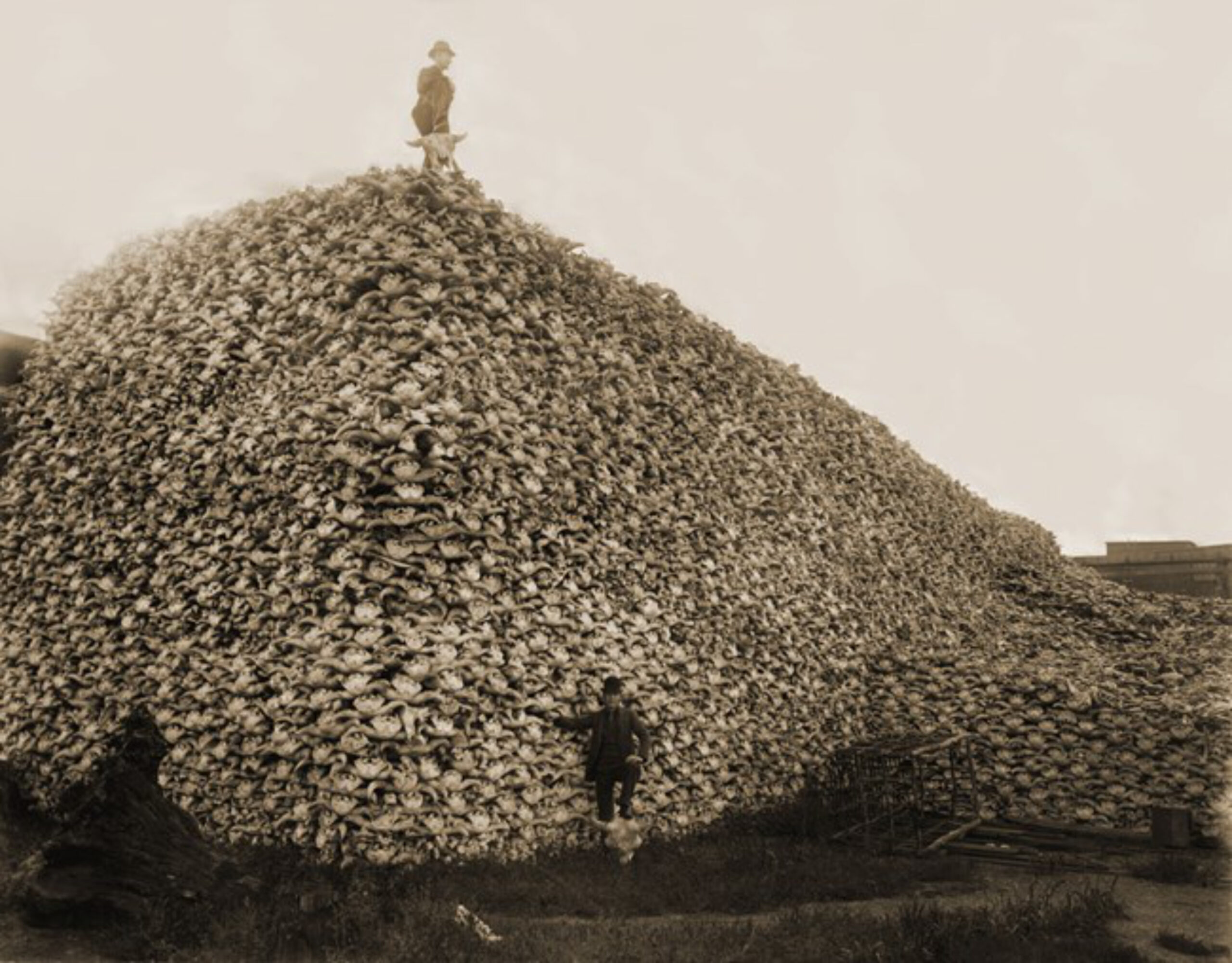

Certainly, President Grant presided over one of the worst examples of ‘inefficient use’, the largest destruction of animals in modern history. Bison went from numbering an estimated 60 million individuals before the 1870s to becoming nearly extinct in the 1880s, due to their mass slaughter over just one decade. A population of just 100 individuals, with 25 going to Yellowstone National Park, survived.

The story of capitalist vandalism of nature has continued ever since, unlimited extraction and destruction against the background of a plethora of meetings, pledges, treaties, conventions, and institutions being created, by the so-called congress elite, to supposedly stem the decline of biodiversity.

Just 20 years on from the extermination of bisons in the US, in 1900, a meeting was held to discuss the similar levels of destruction in continental Africa. That year, international cooperation to conserve the wildlife and natural resources of Africa was first agreed by the then colonial powers of Great Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, and Spain to preserve African wildlife (Belgium did not participate). The aim was to prohibited the killing of certain African animals and “all other animals which each local government judges necessary to protect, either because of their usefulness or because of their rarity and danger of disappearance”. The treaty was proposed because of the rapid depletion of African big game which was being hunted for business and sport by Europeans, with a secondary motive being to preserve the remarkable and novel wildlife and fauna of the continent.

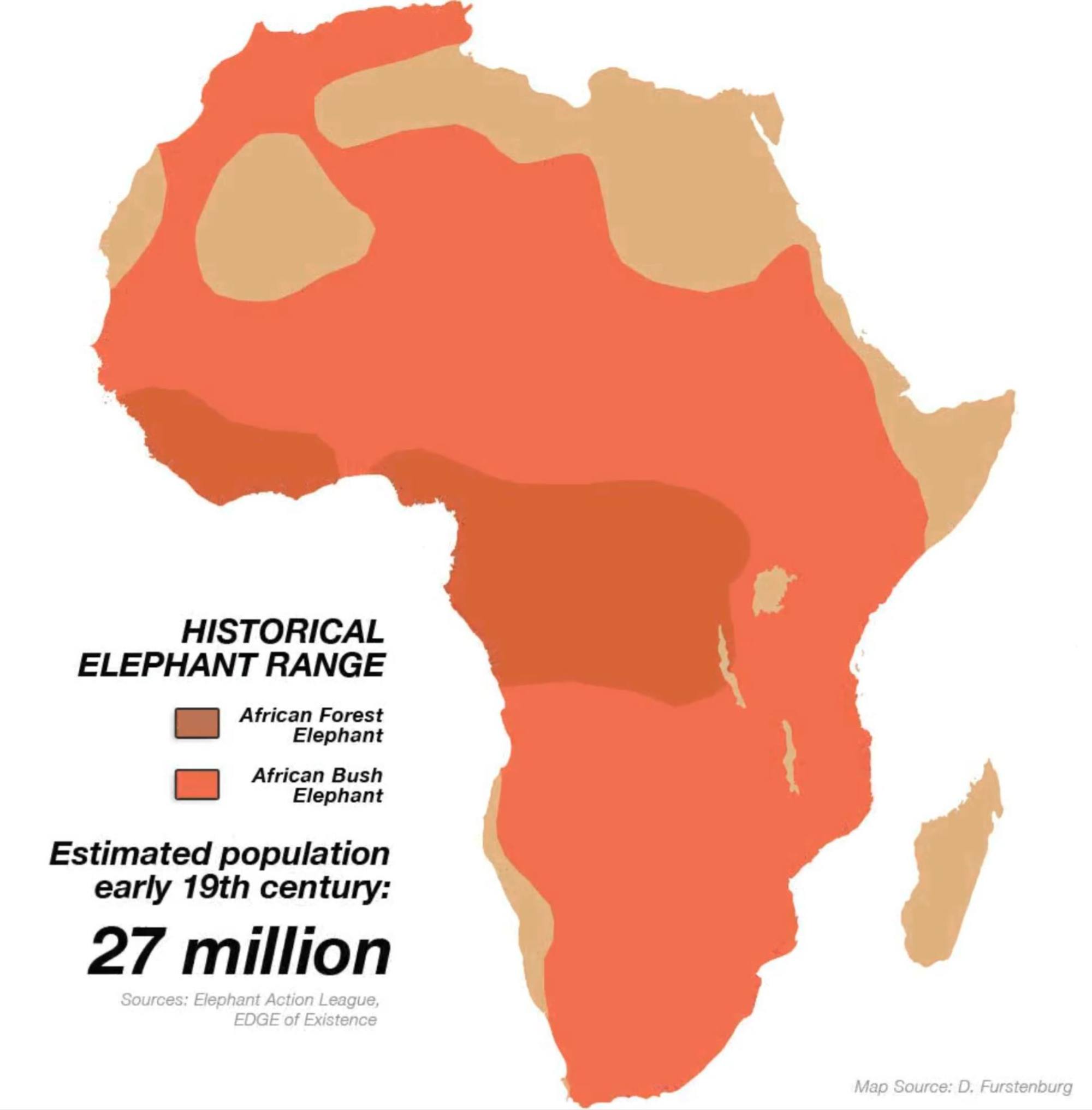

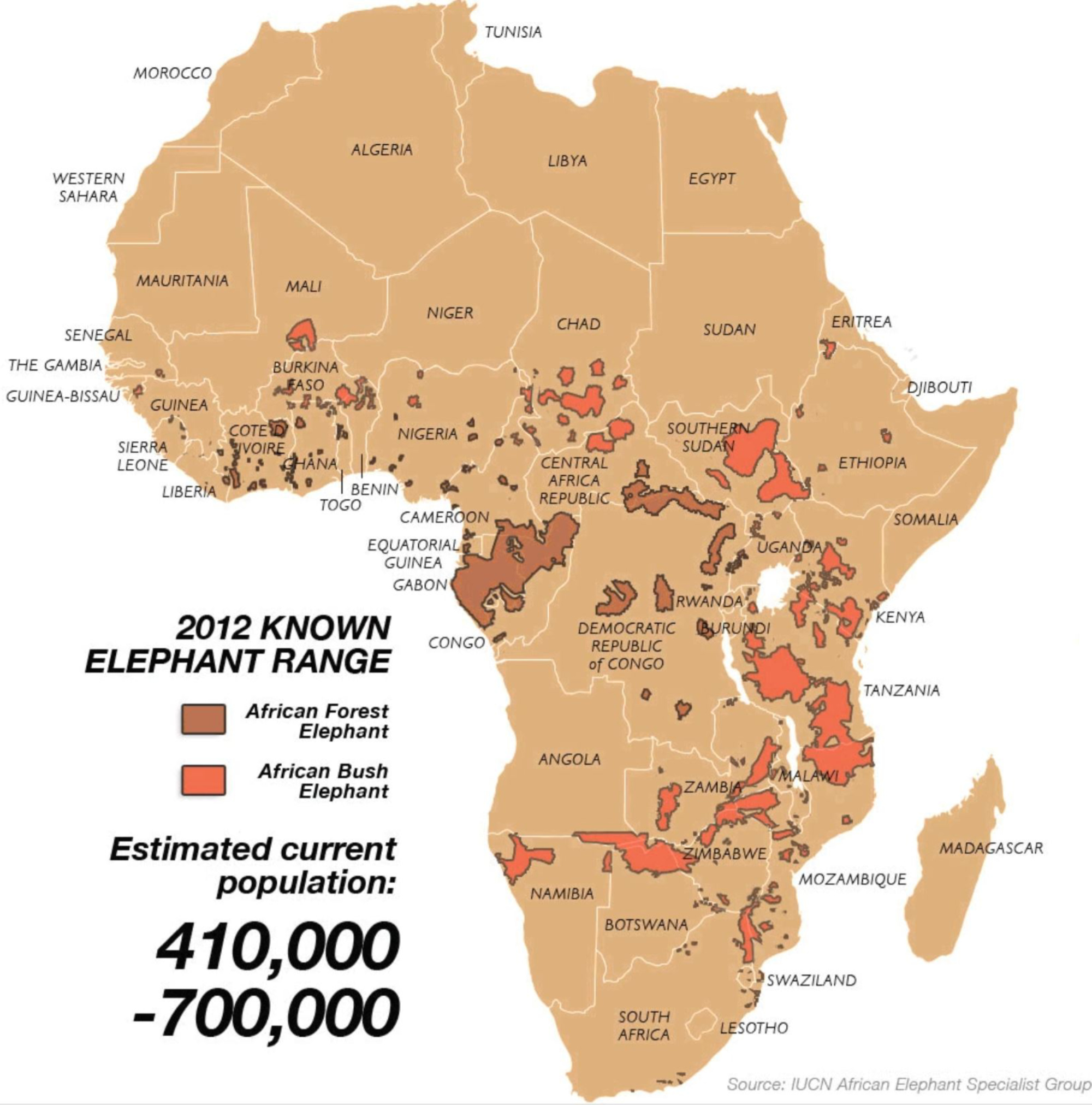

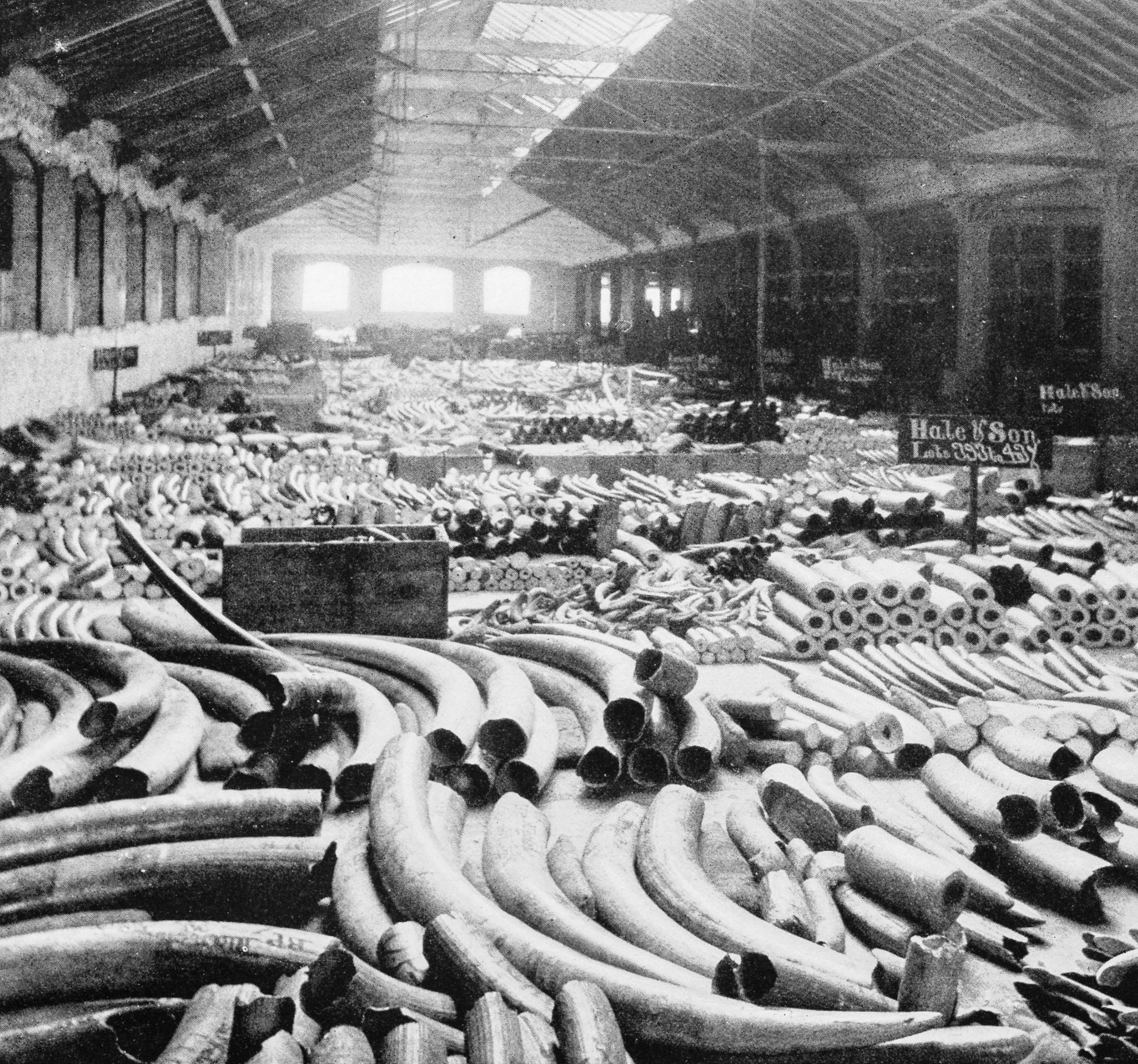

Just one example – the hunting of elephants was particularly excessive during the colonial period, with the British being the worst culprits, played a significant role in the African elephant’s population crash. The current estimate of the African elephant population is just 415,000, down from around 27 million in the early 19th century.

The scale of elephant and bison annihilation is a result of too few people considering the words of Henry Beston, writer and pioneer of the modern environmental movement, who said, “The creatures with whom we share the planet and whom, in our arrogance, we wrongly patronize for being lesser forms, they are not brethren, they are not underlings, they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the Earth”.

By 1933, in Africa again, the Convention Relative to the Preservation of Fauna and Flora in their Natural State, also known as the London Convention, was agreed among colonial powers. It has been called the Magna Carta of wildlife conservation. The Convention obligated signatories to, “establish parks and reserves and limit human settlement therein, to domesticate useful animals, and to prohibit unsportsmanlike methods of take. It also required states to give special protection to a list of species.”.

Yet, the myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, went on.

By 1948, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was established to monitor the status of the natural world and the measures needed to safeguard it. Over the years this evolved into its stated mission to, “Influence, encourage and assist societies to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable”. At the time of its founding IUCN was the only international organisation focusing on the entire spectrum of nature conservation. In 1949, the organisation drafted the first list of “gravely endangered species”.

Lack of funding for research and protection has always been an issue, so in 1961, to establish a stable financial basis for its work, the IUCN participated in setting up the World Wildlife Fund, conceived as an international fundraising organisation to support the work of existing conservation groups, and primarily the IUCN itself. By 1964, the IUCN published its Red List Data Book. From this date on, the lack of awareness cannot be put forward as an excuse for the continued destruction of nature.

Around the same time, in 1968, the Club of Rome was founded to look at the problems of humankind —environmental deterioration, poverty, health, urban blight, criminality. The club’s first report, Limits to Growth, suggested that growth of production and consumption could not continue indefinitely on a limited planet.

Despite the mounting evidence to the contrary, the myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, went on.

Instead of changing course, we see a continuation of the previous pattern – establish more institutions that monitor and report on the problem but do nothing of substance to halt the vandalism.

In this vein, the World Economic Forum was founded in 1971, as a platform for resolving international conflicts, including the conflict over resources. In 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm was the first world conference to make the environment a major issue. The outcome – Stockholm Declaration – contained 26 principles. Principle 2: “The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and especially representative samples of natural ecosystems, must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate.”.

The conference led to the establishment of:

- In 1972, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), with a mandate to, “provide leadership, deliver science and develop solutions on a wide range of issues, including climate change, the management of marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and green economic development”.

- In 1975, the launch of the Convention of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). CITES was set up to address the depletion of wild species resulting from demand for luxury goods such as furs in Western countries to ensure sustainable offtake.

The “through careful planning or management” of Principle 2 has never really eventuated. As early as 1981, at CITES CoP3, just 6 years after coming into force, it was recognised by some that this model would fail.

Australia submitted a proposal to move CITES trade to a reverse-listing model (a precautionary principle model, where the default is no trade without upfront research to prove it can be sustainably managed). Australia correctly predicted that under the agreed CITES model – where trade is unrestricted until it is proven to be a problem – trade will grow quickly and CITES will lose control.

The reverse listing model was rejected, the species traded under CITES has grew from 700 in 1981 to over 40,000 today and CITES lost control.

Yet, the myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, went on.

The World Resources Institute (WRI) was established in 1982 by Gus Speth, who once said, “The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy…and to deal with those we need a cultural transformation”.

As it becomes ever more apparent that the earth’s systems were starting to break down, 1992 saw the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Rio de Janeiro Conference or the Earth Summit. This led to the establishment of the Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1992) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, 1993). The CBD’s stated 3 main objectives are:

- The conservation of biological diversity

- The sustainable use of the components of biological diversity

- The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources

This period also sees the first-ever global funding mechanism for biodiversity preservation – The Global Environment Facility (GEF). The GEF pools donations from 40 donor countries for distribution to its members, now 186 countries. Despite mounting evidence of rapid decline of biodiversity, the funding continues to hover around US$ 1 billion pa, or 0.001% of world GDP. This pocket change level of funding seems particularly stupid when it is acknowledged that more than half the world’s GDP (USD 44 trillion) is dependent on nature and the services it provides.

In the absence of useful funding and mandatory regulations we see instead the continuation of the pattern – new committees and institutions are being created, none of which threaten the status quo.

As early as 1994, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) agrees to set up its own Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE). The CTE was set up with the mandate to 1) identify the relationship between trade measures and environmental measures in order to promote sustainable development and 2) make appropriate recommendations on whether any modifications of the provisions of the multilateral trading system are required. While the WTO primarily acts as a regulatory framework to facilitate international trade, with the CTE it formally accepts that under WTO rules additional checks and regulations are permitted in cases where trade could negatively affect the environment.

At the WTO Trade and Environment Week of 2022, WTO Deputy Director-General Jean-Marie Paugam states, “The recently concluded Fisheries Subsidies Agreement prohibits subsidies for illegal and unregulated fishing. It is the first WTO agreement with sustainability at its core”. Given Paugam’s opening statement about the Fisheries Subsidies Agreement being the first WTO agreement with sustainability at its core, just what has the CTE being doing for the last 30 years? Because it appears to have been asleep at the wheel! This makes it even more puzzling that Paugam singled out the CTE in his opening address, saying “the CTE carr[ies] the huge responsibility of making all this happen”.

After the CTE in 1994, in 1995, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) is launched; a CEO-led organisation of over 225 international companies. The door to businesses directly participating in the ‘regulation’ of extraction and ‘protection’ of nature had been opened.

The first evidence of this is found in the classification of protected areas. By the early 1990s, Hayden’s ‘vandals’ were no longer willing to tolerate land being set aside for protection. Following the 1992 IUCN World Parks Congress, a new system of categorising protected areas (PA) was developed, with new categories introduced that allowed resource extraction. These new types of ‘protected areas’ were in place by 2002. The authors of a 2005 paper, “Rethinking protected area categories and the new paradigm”, made very clear their assessment of the new categories, going as far as saying “Category V has been used or proposed for use in a manner that tortures the notion of PA so badly as to make it unrecognizable”, and concluding, “The vision of a humanised PAs presented by the new paradigm will lead to a biologically impoverished planet”. Most growth of protected areas in the years since have been in the new categories that allow extraction to continue.

The myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, goes on.

By 2010, biodiversity loss was gaining more public attention. At the CBD CoP10, signatories agreed on 20 targets to stem biodiversity loss by 2020, the “Aichi Biodiversity Targets”. Also in 2010, the United Nations General Assembly urges the United Nations Environment Programme to establish the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services IPBES; it is launched in 2012.

In 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 global objectives are established as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. They contain several goals to protect the environment, but these are in contradiction to the majority of goals, which push for development and growth to ‘solve’ global issues.

By 2019, research into the Sustainable Development Goals confirms they prioritise economic growth over sustainable resource use.

The myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, goes on.

The 2019 landmark IPBES Global Assessment report established that trade is the biggest extinction risk for marine species and the second biggest risk for terrestrial and freshwater species.

As 2020 rolls around, the world fails to meet a single one of Aichi Biodiversity Targets to stop destruction of nature. The setting of new goals is delayed 2 years because of a global pandemic, zoonotic in origin; ecosystems are letting the world know just how stressed they are. Two years late, at CBD COP15, signatories agree on 23 targets for 2030, the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)”, to stem biodiversity loss. Given the CBD’s 3 main objectives, a key target is Target 5, which states unsustainable and illegal extraction of biomass must be stopped by 2030.

By October 2024, at CBD CoP16, more than 85% of signatory countries miss the deadline to provide national action plans, CoP16 ends in disarray and indecision. This is worth repeating, 85% of signatory countries miss the deadline to lodge their ‘plan’ of action. With only 5 years left to the goal and target deadline, ‘planning for action’ has stalled; no one is talking about actual action!

All this while the 15th edition of WWF’s Living Planet Report confirms a catastrophic 73% decline in the [global] average size of monitored wildlife populations over just 50 years (1970-2020); Latin America and the Caribbean, have recorded a staggering 95% average decline.

Given that all these institutions, meetings, pledges, conventions have not changed the underlying model – the default remains unlimited extraction and the myth of inexhaustibility, perpetuated to benefit the few, goes on.

Nature Need More can with 100% certainty state that there is No Chance of achieving GBF Target 5 by 2030. Please note, we would be VERY HAPPY to be proven completely wrong on this, though all the evidence presented means that is extremely unlikely.

The idea that businesses will voluntarily adopt and pay for ensuring the legality and sustainability of their supply chains ought to be confined to the dustbin of history by now. For those that are still unsure, I would recommend a 2009 book, From Predators to Icons. The authors challenge the image of the business entrepreneur as a visionary with a plan. Instead, they outline their use of the term ‘predation’, as, “ruthlessly taking advantage of imperfections, weaknesses, and vulnerabilities within the market”. Imperfections, weaknesses and vulnerabilities that have grown since the 1980s, with the significant scaling back of mandatory government regulations. In the book, Michel Villette, a sociologist, and Catherine Vuillermot, a business historian, examine the careers of thirty-two of wealthiest global executives in order to challenge the conventional explanations for their extreme success and come to a better understanding of modern business practices. For those who are excited about Musk’s and Thiel’s men entering The Whitehouse this book may be the reality check needed.

The exploitation of the imperfections, weaknesses, and vulnerabilities within the market has created the extinction crisis, climate change and inequality. The vandals are not the people gluing themselves to corporate headquarters or throwing soup at paintings protected behind glass.

To misquote Joesph Wood Krutch, “If people destroy something replaceable made by man, they are called vandals; if they destroy something irreplaceable made by thousands of years of evolution, they are called entrepreneurs”.

We are two weeks away from the start of the 2025 Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland, a meeting author Anand Giridharadas called, “a family reunion for the people who broke the world”. The composition of the conference (congress) elite, who have gathered at such meetings since 1900, may have slightly changed, but the new entrants have perpetuated the entrenched values, “Despite calls for reform, the way conservation was conceived, changed only to a limited extent in the short twentieth century. The small conference elite did establish new and more diverse connections, but it also guarded the contours of an old project”.

Numerous schemes, treaties, conventions and institutions have achieved nothing in the last 150 years. We finally need to accept that they are there to perpetuate the myth of inexhaustibility so the elites can benefit from the overextraction, overproduction and overconsumption of the little that is left. Only then can we collectively make an informed choice about the global systems needed to save the remaining wonders from becoming nothing more than merchandise.