South Africa is currently pushing a pro-trade agenda in rhino horn, in the hope of getting a trade legalisation decision at a CITES meeting to be held in South Africa in 2016. The stated objective is that only legalising trade will stop the poaching by driving down black market prices for rhino horn. This is being justified by claiming that all other anti-poaching and demand reduction measures must have failed since the poaching rate is still increasing.

With a complex issue such as legalising the trade in a currently illegal wildlife product it pays to analyse the motivations of the various players involved, as the so-called ‘rational’ (economic) arguments put forward can be adjusted to fit favoured outcomes. Governments are adept at justifying political decisions with claims about positive outcomes. This is usually not much of a problem because these decisions rarely involve significant downside risk. The question of the legalisation of the trade in rhino horn is immensely complex AND involves a massive downsize risk – the risk of rhino extinction in the wild. Hence all arguments need to be examined in light of the true complexity of the problem and the size of the risk involved.

In the first instance the claim that anti-poaching measures must have failed because the poaching rate is still increasing is disingenuous. Poaching rates are extremely low in well-protected conservancies and in areas where horn-devaluation has been used (by infusing horn with toxins and dye). Most poaching takes place in National Parks, especially in Kruger National Park. Serious anti-poaching measures have in the main only been put in place in the last 1-2 years, in line with the escalation in poaching attempts.

©Jerm. Many thanks for use in BTB blog.#

The problem is not that proper anti-poaching measures don’t work, the problem is that they are very expensive compared to the operating budgets of National Parks and conservancies. If anti-poaching measures are successful they will further restrict supply, thereby increasing black market prices. Increased prices in turn will justify the increasing uses of high-tech poaching methods, e.g. through the use of helicopters, surveillance and trained personnel, which then further escalates the cost of anti-poaching measures and so on. The fundamental question therefore is to what extend can National Parks and conservancies keep investing in protection measures given that these result in no economic benefits other than keeping the animals alive?

This consideration is vital, as the escalation in poaching has done nothing to increase ‘rhino tourism’ and most conservancies have had to find significant donations or make other operational savings to cover their anti-poaching expenses (which run into millions of dollars per year). The question of economic benefit to offset increased costs is at the heart of the trade legalisation argument. South Africa sits on a stockpile of 18 tons of rhino horn. Being able to legally sell this amount of horn, even if legal prices were to be substantially lower than the current black market price, would go a long way towards covering protection expenses.

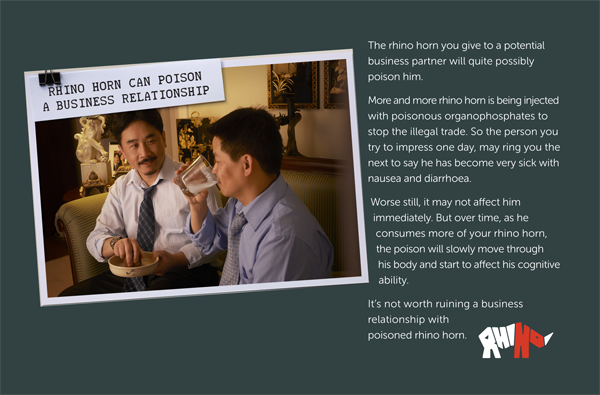

The problem is, it wouldn’t necessarily stop the poaching. The potential risk lies in the nature of the demand. Rhino horn is not a commodity, it has no known substitutes in the eyes of the consumers in Viet Nam (primarily) and China. The current demand is two-fold, with the main source of demand being newly rich businessmen in Viet Nam who use rhino horn as the ‘millionaires detox drink’ and as a status symbol, giving gifts of horn as they negotiate business deals. The second source of demand is in traditional Chinese medicine, primarily as an ingredient to reduce fever and inflammation and the more recent perception that it can help as part of a cancer cure.

The worry in terms of legalising trade lies with the status driven part of the demand. These consumers have no interest in reduced prices (horn is a store of value and therefore subject to speculation on increased prices) and they will likely adapt their preferences if trade is legalised. We have already been told by one user in Viet Nam that he would happily buy the last rhino horn and price is not a problem. Similarly, users express a preference for ‘wild’ rhinos and could easily reject legally traded farmed or stockpiled product to protect their investment. This has happened before with tiger skins – farming tigers in China has not reduced the amount of poaching of wild tigers for this very reason. Hence the price for poached rhino horn is likely to stay high and will not be influenced greatly by the legal trade. Demand will continue to increase based on increased wealth and inequality in Viet Nam – as with all luxury products the demand is not price sensitive, it is only dependent on the perceived status gain and the number of people able to afford it; and the number of people who can afford the genuine article is going up all the time.

In addition there are major complexities associated with creating a regulated legal trade that prevents laundering of illicit products and stockpiles. Creating such a market requires full participation from governments that have to date shown little interest in effectively enforcing their own legislation when it comes to smuggling and consuming illicit wildlife products. How such a market would operate and who would cover the associated enforcement costs has not been discussed in detail in any of the arguments put forward in support of trade legalisation.

What all the pro-trade literature put forward recently does is discount the possibility of influencing demand for rhino horn, based either on cultural considerations or on the failure of the measures tried so far. The assumption that status conscious newly rich Vietnamese will continue to want to acquire and use rhino horn is convenient in this respect, but it is also wrong.

To date, no effective campaign has attempted to directly target these primary users. The dollars spent on demand reduction are tiny compared to protection and conservation. Recently one USA based conservation organisation told Breaking The Brand that 2% of their rhino protection budget goes towards demand reduction initiatives; and in reality those were more awareness raising to the general community in Viet Nam and China rather than campaigns to create behaviour change in the primary user groups.

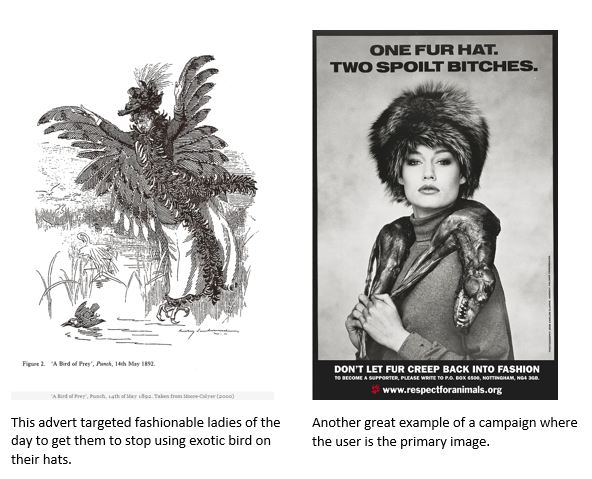

Historical evidence from the plume-boom and anti-fur campaign show that status-driven consumption can successfully be undermined with the right approach.

With the right campaign and placements in media consumed by the primary users the speculative, status driven demand spike can be broken. Then prices for rhino horn will collapse back to historical levels based on use in traditional Chinese medicine. At those price levels poaching is economically no longer attractive, as evidenced by the extremely low poaching levels between 1993 and 2007.

It would appear that the people pushing the pro-trade argument have invested little into understanding the primary users of rhino horn and the nature of the demand. The pro-trade arguments being put forward are unsophisticated and put the rhino at great risk. It is also premature given minimal investments that have been made to-date in strategies targeting the actual users of genuine rhino horn in a way that has a good chance of changing their purchasing behaviour

See the example ad from our pilot campaign on how such targeting would work:

To find out more or donate to this campaign, check out: https://natureneedsmore.org/btb-campaign-examples/

Breaking The Brand (now Nature Needs More) is run by volunteers who cover their own administration costs so 100% of donations go towards publishing the campaign in Viet Nam.