Biggest Profiteers From Biodiversity Loss

Much has been made of the trade in wild species supposedly supporting the livelihoods of poor communities in the Global South. Poverty alleviation is used by many players as an argument to continue and expand the legal trade in endangered species. But who really benefits from the trade that is driving the extinction crisis?

The biggest profiteers from the legal trade in wild species are some of the richest countries and regions of the world. The main import markets are the US, EU/UK, China/HK and Japan. They are also some of the largest luxury companies and conglomerates in the world. After seafood, fashion and furniture are the biggest users of wild species as their raw materials.

Growing public awareness of biodiversity loss means these businesses, their shareholders and governments have needed to do something to ensure that this trade goes unchallenged. Fossil fuel companies have invested in undermining climate science with disinformation, but this strategy was not possible for biodiversity loss.

Thankfully, conservation organisations and academia have been monitoring the decline of species for decades. As a result, it has been long established that trade is the biggest extinction risk for marine species and the second biggest risk for terrestrial and freshwater species. Research has further established that international trade is the major culprit for unsustainable extraction, not community use or local trade.

In this instance it was hard for business, which use wild species as their raw materials, to use the same disinformation and propaganda used to delay climate action. In the case of biodiversity loss, they can’t “reposition biodiversity loss as a theory, not a fact” or pay for advertorials on the “weak” evidence, and “non-existent” proof.

Instead for the last two decades and more, business have focused on producing glossy sustainability reports, paying for sustainability advertorials and supported the rise of sustainability journalists and editors.

New jobs have been created, namely sustainability directors, managers, officers, consultants; as have new organisations and networks.

While companies have invested in the SUStainability game, they have invested nothing in the corresponding transparency. Let’s be clear, sustainability without the corresponding transparency is just a ‘SUS’, neoliberal ideology to maintain shareholder primacy.

As a very minimum, radical supply chain transparency is needed to take the SUS out of SUStainability Game.

It has only been in the last couple of years that some of the big players in conservation have started to openly state that the legal trade is at least 10 times higher in value than the illegal trade, and, despite this, very little good quality, complete data exists. In 2025, some in conservation have started discussing that the sector must Evolve or Perish, based on, “the need to fundamentally reconsider what we label ‘success’. Often, outputs rather than outcomes are celebrated, many stopping short of conservation impact”.

While this statement is true, what isn’t acknowledged is that the limited conservation results of tackling wildlife crime have been because a key suspect was taken out of the frame. The reason so few inroads have been made in dealing with wildlife crime is because in reality there is too big an overlap between the illegal trade and corporate, green crime. Business surveys show that companies know that green crime exists in their supply chains. They also know they can carry on with impunity because there is so little appetite to deal with corporate crime; as a consequence nothing decisive will/can be done in dealing with the illegal trade in wild species.

Supply Chain Crime: Hidden In Plain Sight

Businesses are well aware that illegal, environmentally damaging activities are happening in their supply chains. What they also know is there is little risk of being challenged on this and they can carry on, business-as-usual, without fear of repercussions.

So what does global business know?

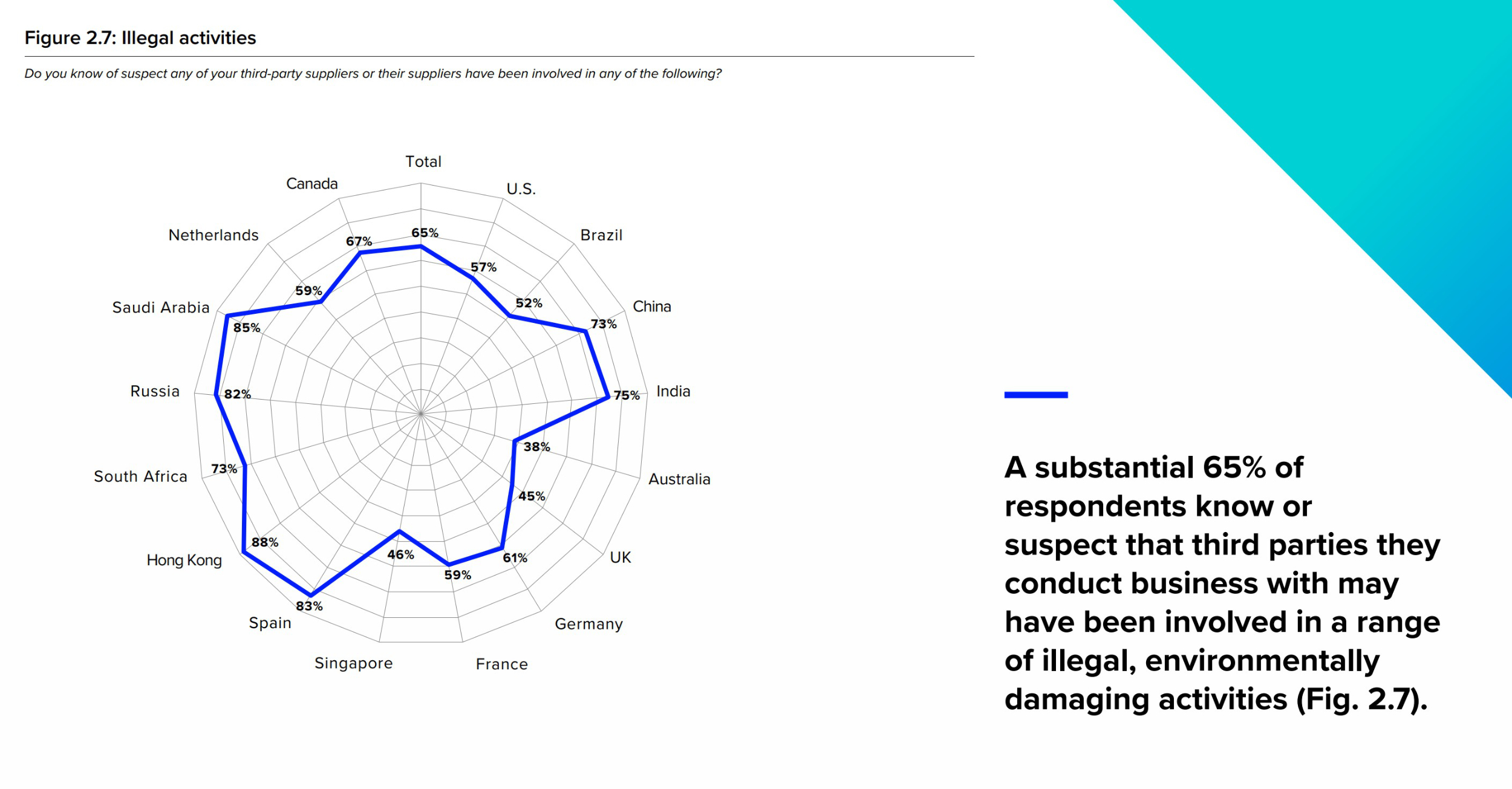

A 2020 report by Refinitiv (one of the world’s largest providers of financial markets data serving over 40,000 institutions in 190 countries, which is now part of the London Stock Exchange Group, Refinitiv UK Holdings Limited) highlights the scale of supply chain risks going unreported and undetected. The survey and report revealed that:

- A substantial 65% of respondents know or suspect that third parties they conduct business with may have been involved in a range of illegal, environmentally damaging activities.

- Only 16% of respondents say that they would report a third-party breach externally and only 53% said they would report it internally.

- Critically, 63% of respondents agree that the economic climate is encouraging organisations to take regulatory risks in order to win new business.

The report (again) confirms why it is so easy to launder illegal product into the legal supply chain and marketplace. and this survey was done pre-COVID pandemic. Monitoring and regulations in trade were softened in many countries under the guise of a Covid-19 economic stimulus strategy.

While the levels of green crime outlined in this report go beyond the CITES trade in wild species, it is important to note that many of the countries highlighted in Figure 2.7 of the report still use 1970s paper permits to facilitate their trade in CITES listed species. For example, Spain where 83% of respondents know or suspect that third parties they conduct business with may have been involved in a range of illegal, environmentally damaging activities, still uses CITES paper permits, as do India (75% of respondents), Russia (82%), Canada (67%), Germany (61%), the Netherlands (59%), the UK (45%) and more. These wealthy countries, and the companies that call them home, have not taken the most basic, pragmatic steps to ensure that illegally harvested wild species can’t be laundered into company supply chains.

In a world where big data rules, to provide a competitive advantage in the globalised and hyper-competitive world of business, the systems, such as the CITES, have been left to languish in a pre-digital world. This is no mistake. Opaque, ineffective monitoring allows businesses and industries to maintain plausible deniability of their role in the biodiversity crisis. They can continue their all profit, not responsivity approach expected by their investors, as a result of the shareholder primacy model.

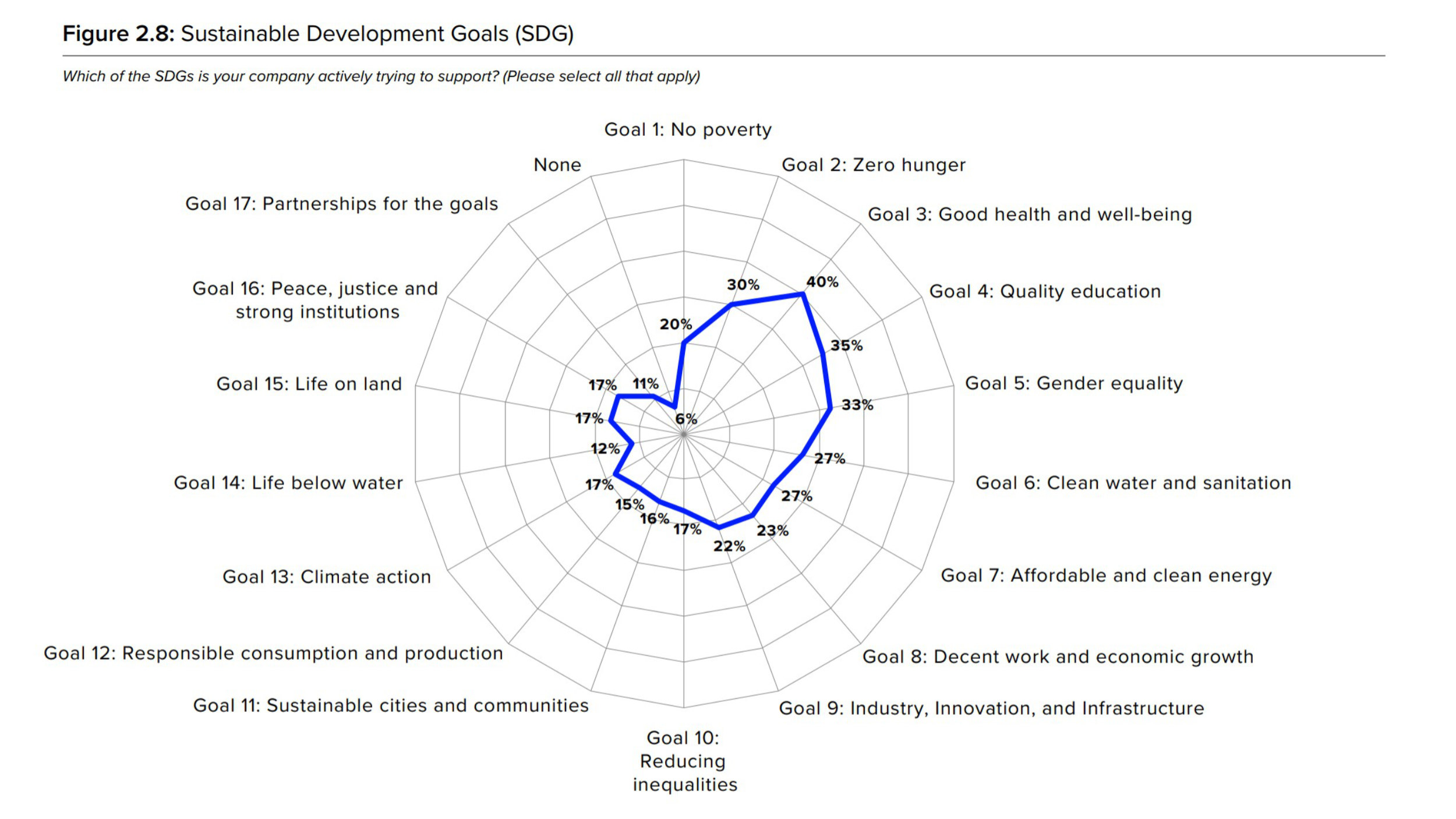

Maybe Figure 2.8 of the report is the best indicator of how much business know they will not be held accountable for their role in the global biodiversity crisis. And specifically, the UN Sustainable Development Goals 12 (Responsible consumption and production) and Goal 15 (Life on Land). Of the global business surveyed only 15% are “trying to support” SDG12 and only 17% are “trying to support” SDG15. Given this report was published in 2020, it is likely that commitments to these and other SDG goals have dropped, in the global push to reduce already ‘non-excitant green compliance’.

The failure of supply chain management, highlighted by this 2020 survey, enabling industrial scale green crime represents a failure of business, industry, markets and investors. It is time to demand that all businesses, including personal luxury (clothing, accessories, Jewellery, beauty, wellbeing etc), high-end furniture and housewares, luxury hospitality, fine dining and gourmet food and the exotic pet industry, involved in the trade in endangered and exotic species, invest in their inadequate supply chain management systems. Without this the SUStainability reporting is simply ‘SUS’, with the only option being, No Transparency – No Trade.

The Problems With Opaque Supply Chains

It is important to remember that after seafood, fashion and furniture are the industries making the biggest profit from the extraction of wild species. The supply chains of the luxury sector need investment to become radically transparent to protect the endangered and exotic species the industry uses as its raw materials for apparel and accessories.

According to Fashion Revolution, “Luxury brands are notorious for being opaque about their supply chains and have long lagged behind other market sectors when it comes to transparency. The elite fashion houses try to create a sense of exclusivity around their products, leaving most details about the production and impact of their products a mystery”.

When it comes to creating a ‘sense of exclusivity’, perhaps the Hermès Birkin and Kelly Bags have perfected how to drive consumer behaviour by creating something that is perceived as having a unique value. The Birkin Bag even has its own sculpture, by Kalliopi Lemos, titled Bag of Aspirations.

It isn’t unusual to see these to two bags listed as the most expensive bags in the world, even when purchased second hand, because they are too difficult to source new. They have become a regular item at Sotheby’s auctions.

A huge investment is made at the retail end of the supply chain to create the ‘sense of exclusivity’ discussed earlier, but is the same attention paid to the raw materials end?

Let’s look at two species used as the raw materials in the production of the Kelly and Birkin Bag, the Nile monitor lizard and the Nile crocodile.

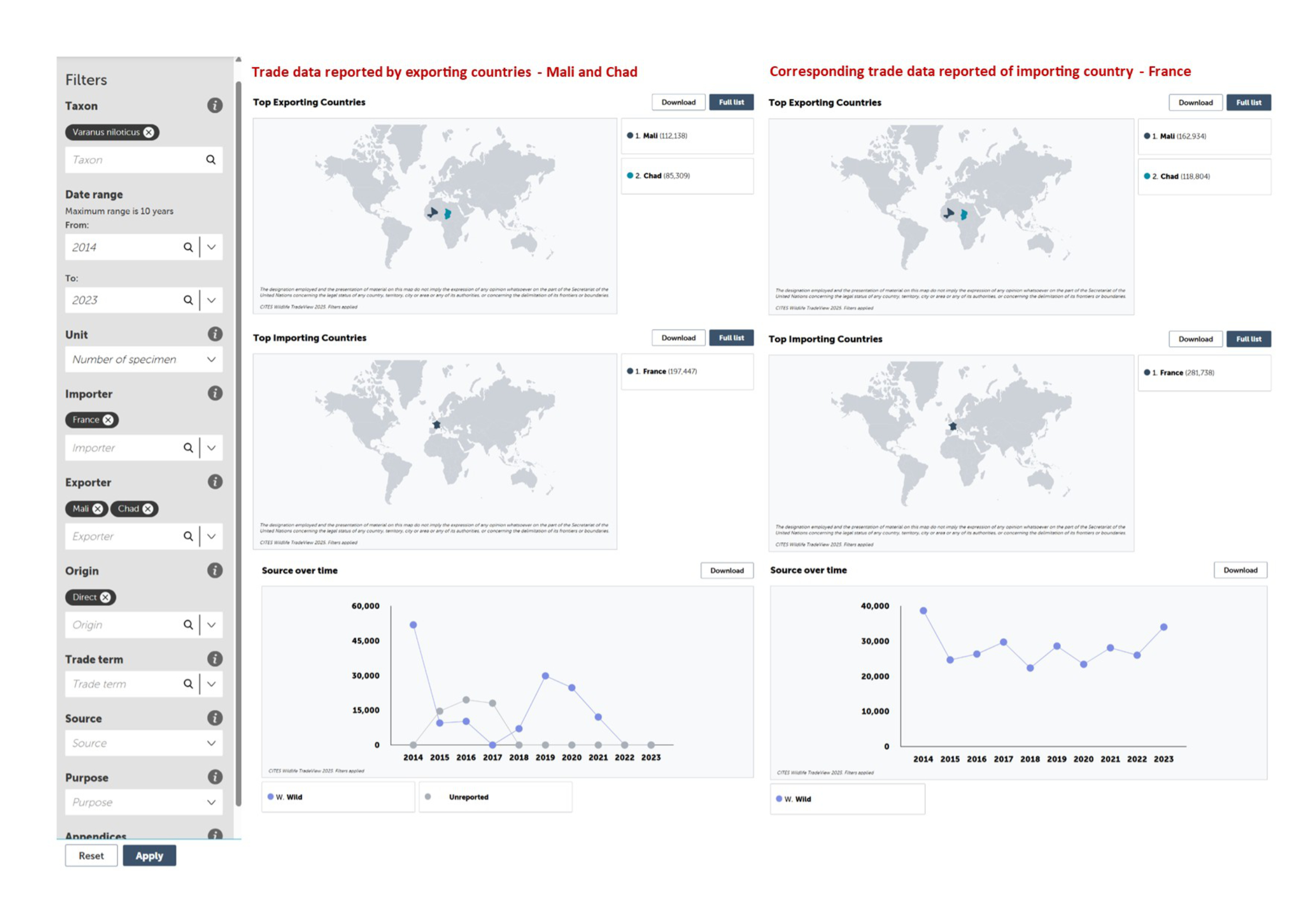

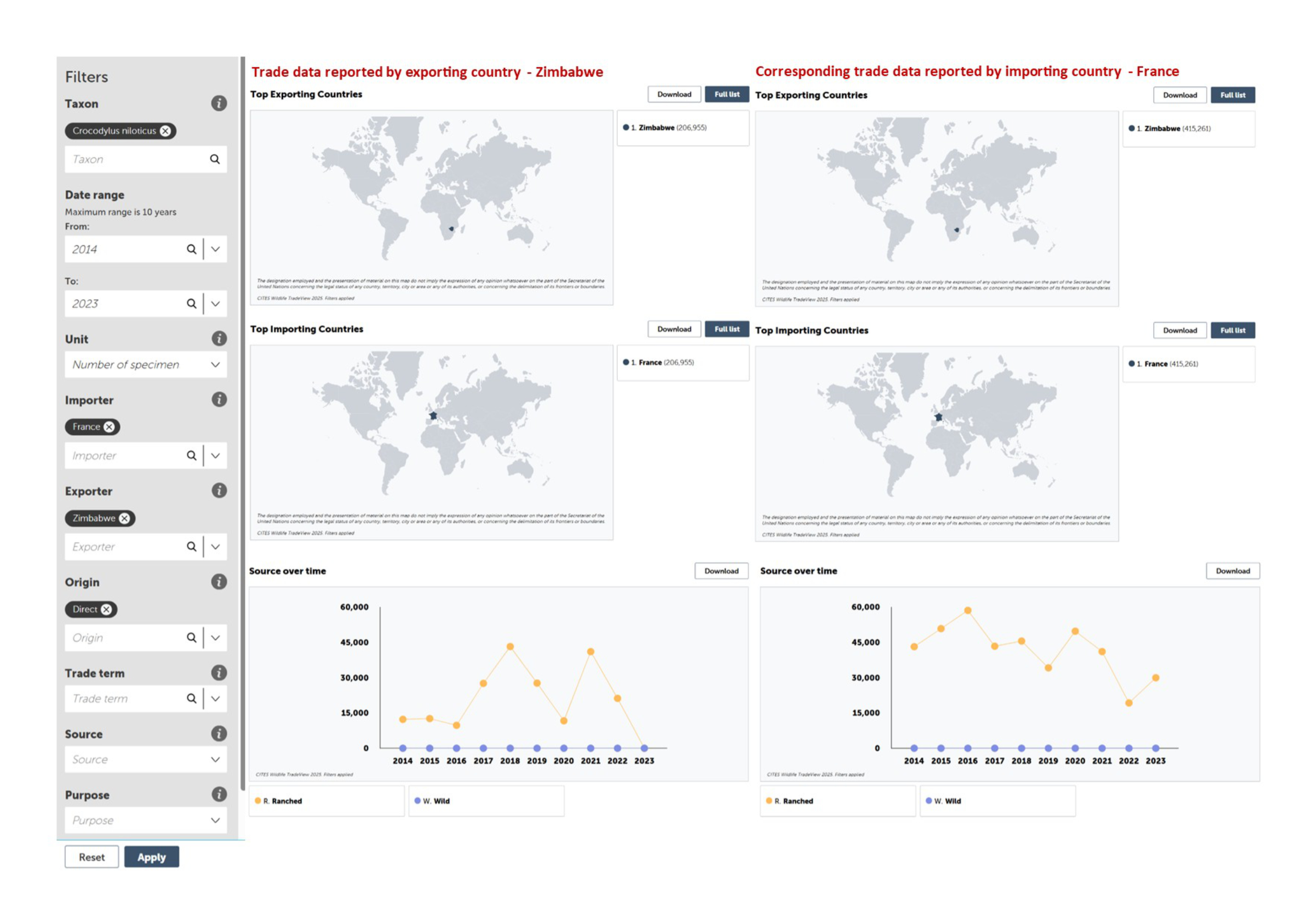

A search of the CITES trade data shows the same problems found in previous investigations. Click on image to enlarge.

The key information that can be taken from these two examples:

- The scale of the discrepancies between the exporting countries (Mali, Chad and Zimbabwe) and the importing country (France) are huge. Between 2014 and 2023:

- Mali stated it exported 112,138 skins of Nile monitor lizard to France, whereas France stated it received 162,934 skins from Mali. A discrepancy of 50,796 skins.

- Chad stated it exported 85,309 skins of Nile monitor lizard to France, whereas France stated it received 118,804 skins from Chad. A discrepancy of 33,495 skins.

- Zimbabwe stated it exported 206,955 skins of Nile crocodile to France, whereas France stated it received 415,261 skins from Zimbabwe. A discrepancy of 208,306 skins.

- The consistent underreporting from exporting countries is a huge risk flag for reasons we will outline in the next section on superfakes.

- For the Nile monitor lizard that is particularly worrying since all the reported extraction is from the wild. Over 52,000 skins of Nile monitor lizard were exported from Mali to France with source code ‘Unreported’.

These discrepancies and problems could be significantly overcome if real-time CITES electronic permits were implemented in every CITES signatory country. The ASYCUDA eCITES, which has been available since 2019, can be implemented for a cost per country of less than US$200K.

So when you think that a Hermès Birkin Niloticus Crocodile can fetch US$225K meaning just 3 bags could pay for the modernisation of the CITES trade permit system in these 3 major trading partner countries, Mali, Chad and Zimbabwe.

While if must be stated that Hermès is not the only luxury brand to use these types of exotic skins as the raw materials in their products, the company’s sustainability statements are consistent with the luxury fashion industry.

Namely, “The Group’s strategy is to better understand its supply chains, strengthen them with high expectations to ensure their quality, ethics, environmental and societal sensitivity, and develop them to anticipate future growth. This approach is based firstly on compliance with the regulations concerning the various materials. This notably means legislative provisions: ensuring compliance with the Washington Convention (CITES), an agreement between States for the worldwide protection of species of flora and fauna threatened with extinction”.

Given the scale export/import discrepancies outlines in the examples for just two species, this makes any company statement on compliance with the CITES meaningless.

Year-after-year CEOs highlight supply chain traceability is the top priority, yet little changes. There may be some minor investment into third party certification schemes. But these are just voluntary, not mandatory and, in the main the information isn’t publicly available for independent validation purposes.

When you contrast the significant investments made by the luxury industry to drive up the desire for their goods and services (e.g. on average the luxury industry diverts 8% of its turnover into funding advertising initiatives), to the fact that the system that monitors the extraction of the ‘raw material’ languishes in 1970s technology, then it is obvious that the industry has zero interest in transparent supply chains and the sustainability of the wild species it uses.

The Deliberate Ignorance of Global Supply Chains

One of the truly strange by-products of globalisation and just-in-time production is the ruthless efficiency yet deliberate ignorance of the global supply chains that make this system work. Today, most, if not all, large companies with global supply chains have no real idea about HOW their supply chains actually work.

They have near-perfect visibility and knowledge of WHEN and WHERE products will arrive for the next step in this vast chain, but the company at the end that puts their brand on the final products would know little or almost nothing about WHO was involved at every step of the way. This deliberate ignorance is particularly significant at the ‘raw materials’ end of the value chain.

From a regulatory compliance and legality perspective this is incredibly convenient as it imparts plausible deniability on the brand owners who are usually in the sight of activists. This is evidenced by the Refinitiv report mentioned earlier, as it is clear that businesses are aware that illegal activity is taking place in their supply chains, but do not care because they don’t have to.

This seemingly strange approach makes perfect sense when you consider that supply chains are optimised for efficiency of supply. When your primary aim is to keep the chain going on-time, on-budget and without interruptions then it is actually beneficial to not know and not care about HOW the chain works and WHO is involved at every step.

As a result of the light-touch regulation of trade, businesses and industries don’t need to care about the HOW or WHO, which enable laundering of illicit products into the legal supply chain.

In practice this means that anything other than the WHAT, WHERE and WHEN of the flow of goods in the chain is treated as a black box and therefore rendered irrelevant. From the standpoint of enforcing the legality and origin of wildlife products, this renders any sustainability statements made by the brand name owners rather meaningless and explains why they are never backed up by any concrete evidence.

Ensuring that all raw materials such as python skins come from legal and verifiable sources means knowing not just the WHAT, WHEN and WHERE at all times, but also the WHO the goods were acquired from and HOW the goods were obtained and processed by the supplier.

As the Refinitiv business survey clarified, “63% of respondents agree that the economic climate is encouraging organisations to take regulatory risks in order to win new business”.

Businesses do not feel compelled to ask any questions about the true origin and legality of the products entering their supply chain. Again using the example of python skin, as long ago as 2014 a report, Assessment of Python Breeding Farms Supplying the International High-end Leather Industry, concluded that while commercial farming of pythons for their skins appeared feasible, it acknowledged that absence of strong regulatory measures, monitoring and enforcement means captive breeding farms for pythons can be used to launder illegally collected or traded animals and skins; giving examples such as:

- Despite large exports of python skins from Lao PDR with a CITES source code C [captively bred], this study found no evidence that python farming is currently taking place [in the country].”, and

- “Python skin exports using a CITES source code “C” from countries other than China, Thailand and Viet Nam (e.g., Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos PDR and Malaysia) should be treated with caution until improved data on farms, management and monitoring systems are in place to verify captive production capacities.

This problem is especially pronounced in the timber trade. Interpol estimates that 15-30% of the global wood trade comes from illegal logging. This astonishing level of illegal trade raises barely a shrug from the (not really) concerned public and the authorities. Businesses involved in the timber trade equally prefer to look the other way. Importers are usually happy to assume that if the timber reached their premises, it must have been obtained legally.

Procurement for any modern corporation is a cost centre driven to relentlessly bring prices down, not to worry about the legality of any individual shipment somewhere deep in the supply chain.

This is one of the major reasons why the legal trade in endangered species and the illegal trade have become so intertwined as to be considered

inseparable. Illegal shipments can only be discovered as illegal if traceability to the ultimate source is possible. Once they have entered a legal supply chain, that will usually only be possible in rare cases where DNA or radioisotope analysis are conducted and can prove illegality.

In 2019, Nature Needs More’s Founder Dr Lynn Johnson was delighted to collaborate on an article, with Dr Catherine Kovesi University, a historian at the University of Melbourne; one of Catherine’s specialist subject areas is researching the discourses of luxury consumption. This peer reviewed article was published in the August 2019 issue of Fashion Theory.

The article, titled Mammoth Tusk Beads and Vintage Elephant Skin Bags: Wildlife, Conservation, and Rethinking Ethical Fashion, explores the fact that wildlife is not currently factored into the evolving sustainable fashion strategy.

Abstract

Recent years have seen marked consciousness-raising in the arena of ethical fashion. Despite inherent difficulties in tracing a complete ethical supply chain back to source, sustainable fashion movements have helped to highlight the need for prominent fashion industry role models on the one hand, and awareness of those who produce what we consume on the other. Yet, repeatedly in such discussions, one of the most fragile components of the luxury fashion business is left out of the conversation – wildlife and endangered species. To date there have been parallel discourses in ethical fashion and in wildlife conservation that rarely intersect and are indeed often in unintended opposition to each other. Even those who attempt to promote an ethical path, or who buy vintage rather than new fashion items of wildlife products, often unwittingly contribute to the accelerated demand for wildlife fashion products from present-day endangered species. The desire to be ethical can, in some instances, even contribute to illegal poaching activity. This article unravels for the first time some of the complexities of the conservation dilemmas involved in the wearing of ancient, vintage, and present-day wildlife products. In doing so it argues we should place wildlife center stage, as an equally important element, in rethinking what it is that we wear.