Introduction

For some years now, the Nature Needs More has been monitoring the evolution of automation and its future impact on the global workforce. We have been encouraged by the growing acceptance of a basic income model as a way to help manage the change to a new global economic paradigm, but remain concerned that it appears to be emerging in a very ‘human-centric’ way.

At the heart of our many failures to create a sustainable civilisation is the mistaken belief that humans are ‘above’ nature, including other animals. Despite the dreams of sci-fi, and some billionaires, we cannot exist outside the biosphere of this planet; at least not for quite some time. We equally can’t solve our social problems without re-learning that we are part of nature and need to respect its limits.

At the heart of our many failures to create a sustainable civilisation is the mistaken belief that humans are ‘above’ nature, including other animals. Despite the dreams of sci-fi, and some billionaires, we cannot exist outside the biosphere of this planet; at least not for quite some time. We equally can’t solve our social problems without re-learning that we are part of nature and need to respect its limits.

The ego-centric belief system that humans are a superior species is quite recent, in its current, extreme form; it is only some 250 years old. Global warming, decline in species, overfishing, land degradation and pollution are all linked to this belief system. In the main, we see ourselves ‘above’ nature and that we have every right to exploit (and overexploit), simply because we can. As more people are becoming conscious of how close we are getting to disaster, it is imperative that the ego-centric worldview is challenged as part of advocating new solutions.

It was with this in mind that in 2016 we asked “Can a basic income model help not just society, but also wildlife and the natural world?” It is great that ideas such as the basic income are emerging, but if they evolve based on the same ego-centric belief system then they will not make the slightest difference. Only adopting an eco-centric belief system will allow us to conceive solutions that prevent ecological disaster.

So how can we test this pragmatically?

We have been working on developing a trial to test if paying a basic income to communities surrounding protected wildlife areas will disrupt poaching and save wildlife populations for nearly a year now. The original idea caught the interest of the basic income community and we were invited to present at the Basic Income Congress in Lisbon in September 2017.

We have been working on developing a trial to test if paying a basic income to communities surrounding protected wildlife areas will disrupt poaching and save wildlife populations for nearly a year now. The original idea caught the interest of the basic income community and we were invited to present at the Basic Income Congress in Lisbon in September 2017.

After the presentation we received strong encouragement from key players in the basic income movement to evolve the concept into a project proposal and to come up with a complete model for the trial that could be tested in Southern Africa. We undertook 3 trips to Zimbabwe, the most recent a 2-week field trip in November 2017 to refine the model, socialise the idea with stakeholders and find potential locations that would be suitable to test the central hypothesis – that paying a (small) basic income to a whole community living on the boundary of a protected wildlife area will significantly reduce poaching and human-wildlife conflict.

The proposed approach is to trial paying a basic income of USD $50 per month to adults and USD $20 per month to children who are living in communities experiencing severe poverty and surrounding protected wildlife areas where there is a high incidence of poaching. The basic income will be positioned to the communities as unconditional, combined with a request that they make a moral commitment on their part to help stop people in their communities aiding poachers and traffickers in any way.

The proposed approach is to trial paying a basic income of USD $50 per month to adults and USD $20 per month to children who are living in communities experiencing severe poverty and surrounding protected wildlife areas where there is a high incidence of poaching. The basic income will be positioned to the communities as unconditional, combined with a request that they make a moral commitment on their part to help stop people in their communities aiding poachers and traffickers in any way.

Given we are proposing a (near) universal basic income for this trial, the project is expected to also significantly enhance the living standards of low-income families (currently living on less than USD $2 per day). The basic income trial is expected to demonstrate significant positive effects on physical and emotional wellbeing, education, health and economic activity in the selected communities.

We are proposing a trial size of 2,500-4,000 adults (defined as age 18+ years) set up as a randomized controlled trial with two control group communities in a similar area. We are further proposing a 2-year trial duration to eliminate seasonal effects often seen in poaching activity. The basic income will be paid to the whole community (e.g. a whole council ward) on the edge of either key wildlife populations, for example Hwange or Matabo NP in Zimbabwe. Payments will be made by mobile phone, with mothers (or surrogate mothers) receiving the basic income for the children.

We are proposing a trial size of 2,500-4,000 adults (defined as age 18+ years) set up as a randomized controlled trial with two control group communities in a similar area. We are further proposing a 2-year trial duration to eliminate seasonal effects often seen in poaching activity. The basic income will be paid to the whole community (e.g. a whole council ward) on the edge of either key wildlife populations, for example Hwange or Matabo NP in Zimbabwe. Payments will be made by mobile phone, with mothers (or surrogate mothers) receiving the basic income for the children.

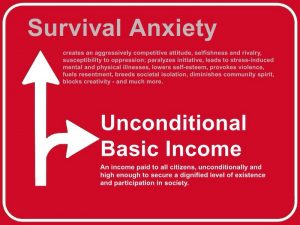

At the heart of our hypothesis that a basic income will reduce or stop wildlife poaching lies the idea that a basic income reduces survival anxiety. Survival anxiety is a specific form of scarcity, as described by S. Mullainathan and E. Shafir in their book ‘Scarcity’. It leads to an exceedingly narrow focus on immediate survival, captures attention, seemingly leads to an inability to plan, paralyses initiative and ultimately results in self behavior and poor decision making.

Why should we expect that alleviating poverty and survival anxiety will reduce poaching? Because it really does not take much to undo the scarcity mindset and because normal cognitive function is restored very quickly once survival anxiety is off the table. In addition, moral considerations and social norms come back into the decision making process once survival anxiety is no longer present.

Why should we expect that alleviating poverty and survival anxiety will reduce poaching? Because it really does not take much to undo the scarcity mindset and because normal cognitive function is restored very quickly once survival anxiety is off the table. In addition, moral considerations and social norms come back into the decision making process once survival anxiety is no longer present.

Further, paying the basic income to the whole community has multiple beneficial effects that will impact poaching behavior. First, it increases the ability to provide mutual support. Poor people receive the most help from other poor people and poor people spend more of their income on helping others than any other group. Mutual support from family, friends and neighbours increases with their capacity to help – hence the basic income will lead to increased mutual support.

Second, paying everyone in the community creates a common bond which can be linked to conservation and care for the local wildlife. The latter contrasts sharply with the currently prevailing common feeling of exclusion from protected areas and the money flowing into tourism or hunting. It is also important to note that, given the levels of poverty around these communities, let’s remember that the majority of people, no matter how difficult their circumstance, aren’t involved in poaching for commercial purposes.

It is also worth noting that this effect cannot be achieved through creating ‘jobs’. Tourism and anti-poaching measures create only a miniscule number of jobs compared to the size of the surrounding communities.

We received a lot of positive feedback on our proposal during the field trip. Whilst initially the response was often ‘What are they going to do with the money if there are no strings attached?’, this objection is easily dispelled using the evidence from the existing basic income trials in Kenya and Uganda (and India and Namibia previously). It is also interesting to look at where this mindset comes from; the relatively recent history of manufacturing people’s worth seeding the idea that paid labour defines your worth and not working is a character flaw. The basic income trials mentioned consistently lead to people working more, not less, and to using the money in creative ways to a secure a future for themselves and their children; including developing a kitchen table banking system in the communities to seed social enterprise.

Paying a basic income also gives people the ability and the time to finally implement the ideas and skills they often have already received from training programs conducted by other not-for-profit agencies. Some people we spoke to acknowledged that they had received great training and capacity building from local programs, but they didn’t have the capital to implement solutions to increase crop yields or minimise human wildlife conflict. Others said, we don’t need any more capacity building, we need capital to implement what we have learnt.

The one, recurring question we got pretty much in every conversation was ‘What happens at the end of the trial?’. It would clearly be counterproductive to simply stop payments at the end of the trial if the concept works and reduces poaching as anticipated.

While we are excited about the number of philanthropists who have shown interest in the model, we wanted to create a mechanism to involve all of anyone who cares about wildlife and social equity; and who have the means to make a small, monthly contribution.

Global First 5000: Pioneers for a Basic Income Linked to Conservation

Our solution is to start the Global First 5000, a community of global pioneers who individually (or as families or teams) pay the basic income for participants in the trial (and beyond). We are looking for 5,000 pioneers who will individually commit USD $85 per month to pay the basic income for 1 adult and 1 child over a 2-year period ($70 is the basic income and the extra $15 covers the anticipated trial overhead costs). The detailed research and model design can be found in the full proposal.

Our solution is to start the Global First 5000, a community of global pioneers who individually (or as families or teams) pay the basic income for participants in the trial (and beyond). We are looking for 5,000 pioneers who will individually commit USD $85 per month to pay the basic income for 1 adult and 1 child over a 2-year period ($70 is the basic income and the extra $15 covers the anticipated trial overhead costs). The detailed research and model design can be found in the full proposal.

From this pioneering group we want to evolve a larger global community if this trial produces the expected results and eliminates or significantly reduces poaching and human-wildlife conflict. We will set up a global Basic Income for Conservation Fund as part of Nature Needs More and expand from the initial trial to covering all communities surrounding a protected area. In a second stage we then want to test a tiered basic income model, which includes incentives to take part in conservation related activities such as rewilding, land rehabilitation and revegetation.

We initially need 2,500 global pioneers to start the basic income trial (USD $5million is the minimum budget to achieve the scale we need to test the central hypothesis). This is an exciting project that has never been done before and we are asking you and anyone who you know be to be part of this project and help us make it a reality in early 2019.

You may be a believer in the basic income, you may join us because you want to help test a new, innovative model to tackle poaching at the source, or you may get involved because you want to tackle social issues in impoverished communities. Whatever your reason, we are excited that you want to be a part of this new global community and support a pragmatic approach to save the wildlife that we love and also support local people to be wildlife custodians and have increased personal opportunities.

Subscribe to our blog posts: