As we approach the 2021 Lunar New Year, on the 12th of February, it is a good time to reflect on this important holiday. The Lunar New Year celebration is the time to usher in prosperity, luck and good fortune for the year ahead. The holiday emphasises the importance of family and has been called the largest annual human migration on earth, as the many people who left regional areas for better job opportunities in cities, travel home to see families. For some parents, who had to leave children with their grandparents in home villages, to look for work, the Lunar New Year holiday may be the first time they will have seen their children in 12 months.

Because of COVID-19, and the new variants, governments throughout Asia are urging their citizens to avoid ‘nonessential’ trips during the holiday period, to prevent a resurgence of the coronavirus. Many regions, including several in Viet Nam, are in lockdown because of recent outbreaks, resulting in a growing number of people asking for travel refunds, as they consider it too risky to visit family.

Has a global pandemic, triggered because the line between humans and animals has long been breached, for trade, finally caused our luck to run out?

Knowing the importance of luck, good fortune and family, in 2015, we ran our first Lunar New Year (Tet) demand reduction campaign in Viet Nam. These Breaking The Brand (to stop the demand) adverts highlighted the health dangers of consuming rhino horn; at the time rhino horn was being infused with organophosphates and ectoparasiticides to deter poachers.

We highlighted that giving rhino horn as a Lunar New Year gift, in either your personal or professional life, could bring bad luck, if people get sick from ingesting rhino horn that had been infused with toxins. The campaigns also talked about the destructive impact of the illegal wildlife trade. While these campaigns highlighted this very specific risk, associated with this narrow, illegal trade, the risks associated with the legal trade of exotic species have, for decades, received too little attention. During this time, world leading epidemiologists have been expecting and preparing for a pandemic, yet the legal trade has gone unquestioned, and is even clinically sidestepped, by the premier conservation organizations.

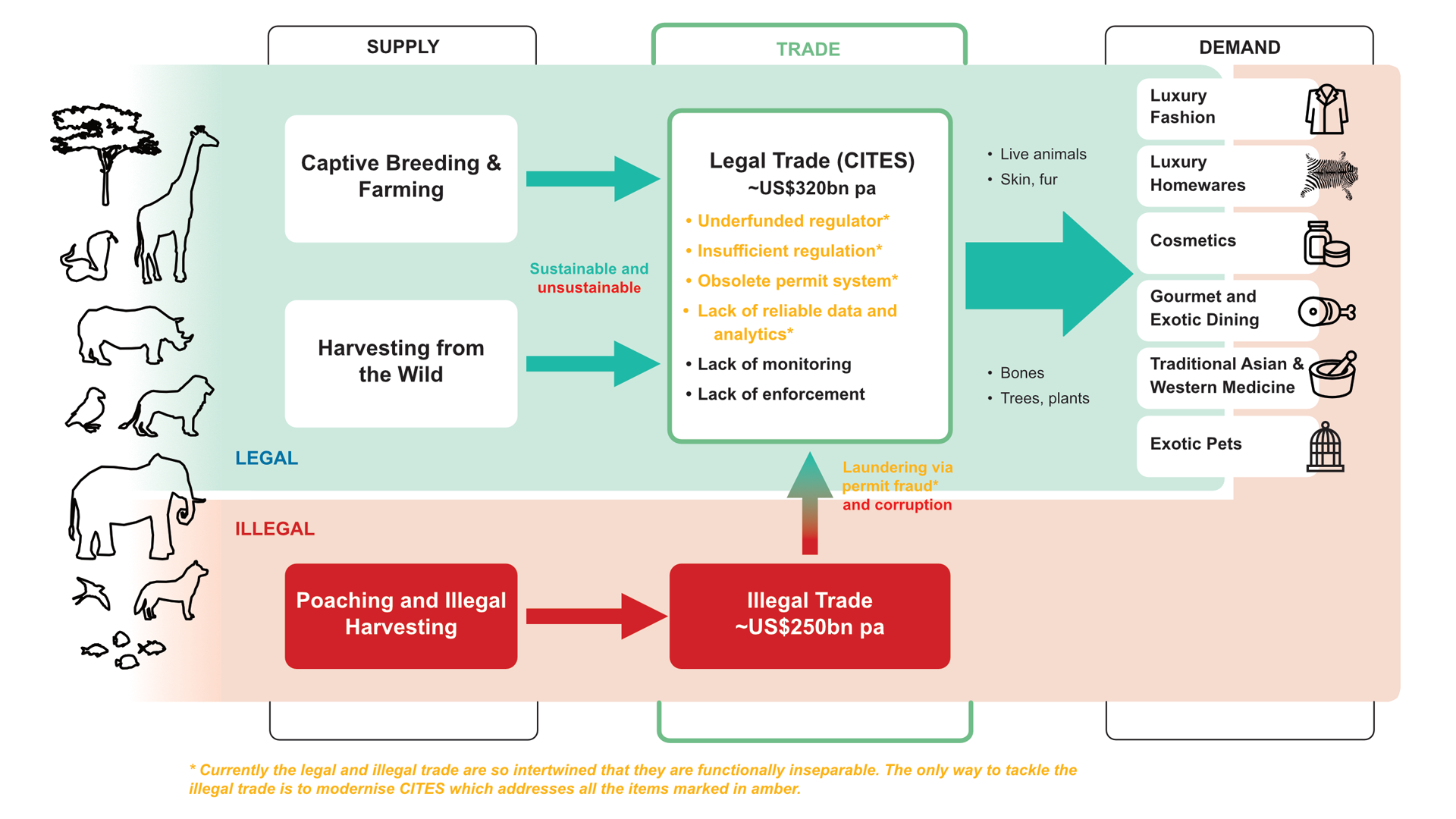

The result is that out of sight and without any real checks, a trillion-dollar trade in birds, animals and plants flourishes. Bizarre as it may seem, even though scientists knew decades ago that a coronavirus disease was going to have a global impact, no one wanted to join the dots and begin to measure the size of the world’s legal trade in endangered species; a shocking oversight that can be traced directly to today’s lost lives and wrecked economies. Few people could have known, before the pandemic, of China’s 22,000, legal captive breeding facilities. In this, China is a microcosm of the world, thriving markets for threatened species exist in many other countries, and supply a number of industries:

The global trade is not only below the radar, there is no radar! The regulator for this trade, CITES, is no longer fit-for-purpose. The massive legal trade, with its minimal oversight and regulation, has enabled the development of poor standards, in the monitoring of the legal exploitation of species, including checking for biosecurity risks. This legal trade was always going to enable viruses to jump hosts; ultimately some of the viruses would jump across to humans.

The reality is that, year-after-year, as we have all allowed the legal trade in exotic and endangered species to grow, unregulated and unchecked, we have been consuming our own ‘gift of bad luck’. Treating nature unthinkingly, and with such disrespect, has come back to bite us all.

But this is not only an individual consumer responsibility, it is a business, markets and investor failure. Pursuing profits, at all costs, and without due regard for the risks can, and does, lead to catastrophes, from oil spills and fires, to biodiversity collapse and pandemics. Governments around the world have capitulated to industry groups, to dilute all aspects of regulation, instead allowing voluntary governance schemes to take the place of ‘real’ regulation. These same business and industry groups have had 50 years to roll out these voluntary systems, they haven’t worked at all to slow biodiversity collapse, and they won’t work.

We have reached a time for real change, a time to update corporate law, so business isn’t legally mandated to maximise shareholder profits. It is time to strengthen and enact the laws governing corporate crime, including green crime, and to appropriately resource regulators such as CITES. This is no longer the time to rely on voluntary governance systems that are, in the main, just PR exercises. The voluntary governance ship has long sailed, and some would say sank!

Updating laws is the starting point, but their enforcement requires oversight by well-resourced regulators, and industry needs to pay for this through fees. Pursuing white-collar crime, and sending business executives to jail, needs to become an accepted norm, which is currently not the case.

Consumers need to think about their behaviour too, as without the desire and demand, the trade in endangered species could not be growing so fast. A 2017 World Customs Union Report quoted the United Nations Environment Programme, who stated that this trade is growing at 2-3 times the pace of the global economy; these are mindboggling numbers.

As consumers, we must ask ourselves, do we really need to consume exotic species? Is the perceived status gain more important than the potential health risks? If consumption of exotic animals continues to increase and wilderness is destroyed for human use, the frequency of zoonotic disease outbreaks will increase as well. Unless we change course and regulate the trade the next pandemic is a certainty. And, it won’t just be rhino horn that brings the gift of bad luck.