The CITES convention is rapidly approaching its 50-year anniversary; the convention was opened for signatures in 1973 and CITES entered into force on 1 July 1975. This milestone cannot pass without CITES providing all the evidence that it is fit-for-purpose, particularly given the looming extinction crisis.

CITES never included a funding model to enable all signatories to adequately resource scientific research, monitoring and enforcement. Far too many signatory countries still lack the mandated scientific authority or a dedicated enforcement authority. Whilst creating a dedicated enforcement authority is optional under CITES, the illegal trade is rampant and growing 2-3 times faster than the world economy overall. This makes CITES effectively a paper convention, impoverished to the point of being useless. The lack of basic population data for most species makes the idea of ‘sustainable use’ meaningless, as evidenced by the 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report.

With most funding to regulate and monitor the legal trade coming from signatory governments and with government budgets under severe pressure worldwide, there is little prospect of a massive increase in total funding to better enforce CITES. Without such a massive funding increase, the 2030 CITES Strategic Vision is not achievable. In addition, as we have seen over decades, government pledges for extra funding are miniscule, inadequate and often not even honoured.

There has been ample evidence that CITES processes cannot adequately cope with the ever-increasing number of listed species, which currently stands at around 40,000. The lack of funding means that in its current form CITES will continue to fail the vast majority of listed species. Listing more species does not lead to better conservation outcomes if funding does not increase in proportion to the number of species listed.

With government and philanthropic funding unlikely to increase significantly, it is therefore inconceivable that CITES in its current form can achieve its primary vision for 2030 without having businesses contribute to the cost of regulation. Such a move would bring this trade in line with other regulated industries where businesses are required to pay fees commensurate with regulatory costs.

In a 2019 presentation, about the need to modernise CITES, Nature Needs More provided a comparison of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). At the time the EMA received an annual budget of €317million (US$375 million [the exchange rate at the time]). Of this nearly 90% of the budget was derived from fees and charges to business. The EMA had 900 staff who processed 60 applications to market new medicines of which 45 were denied. For 2022, the total budget of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) amounts to €417.5 million (US$431million), with around 86% of the budget derived from fees and charges to business, 13% from the European Union (EU) contribution for public-health issues and less than 1% from other sources. Clearly business is paying the cost of regulation here.

Using an image Nature Needs More created in 2019, with the evidence available at the time:

Clearly, to become effective with the current volume of trade the CITES needs a secure, ongoing source of adequate funding, which can only come from the businesses profiting from the trade. It is possible to implement a ‘Business Pays’ funding model, even under the current articles of the convention.

Here, Nature Needs More highlights measures that can be adopted to vastly improve the effectiveness of CITES without the need to renegotiate the articles of the convention. Only with such reform can CITES retain any form of relevance and credibility in line with its stated objective and primary vision for 2030.

Immediate Priorities:

A 1% Levy On Imports To Major Markets

A 1% levy on imports to the main import markets (e.g. US, EU, China/HK, Japan, UK). Research published in 2021 laid bare the countries making the biggest profits from the trade in wild species. An equivalent amount to what is raised could then be contributed by these parties to the CITES External Trust Fund.

Register Of Businesses Trading Under CITES

Establishing a Business Register of companies that trade CITES listed species would improve transparency, data collection and can be used to levy fees for scientific research and trade reviews. Registrations for businesses trading in live animal species or in CITES listed species with revenue above a minimum threshold should attract fees commensurate with annual revenue. Signatories should be encouraged to pass national legislation to make such registration mandatory.

Reversing The Burden Of Proof

Currently the burden of proof regarding the sustainability of trade lies with government departments, IGOs, academic institutions and NGOs which collectively lack the funding to adequately monitor populations and the trade in over 38,500 listed species. Funding further suffers from ‘iconic/ relatable species bias’. Whilst reversing the burden of proof is not possible without a transition to a reverse (positive) listing model, the businesses most profiting from the trade should be asked to make a additional significant contribution to data collection and scientific studies that underpin Non-Detriment Findings and Reviews of Significant Trade.

Such Business Pays funding into the CITES External Trust Fund, could be used to:

- More rapidly roll out CITES electronic permits to move CITES to more transparent and real-time reporting.

- Increase Reviews Of Significant Trade. Reviews of Significant Trade in theory provide a powerful mechanism to ensure that the trade in a species is legal and sustainable. In practice only a handful of reviews are conducted at any one time and the analysis and conclusions suffer from the same lack of funding and of reliable and current trade data as all other CITES processes.

- Create an Enforcement Fund. CITES in its current form does not mandate a dedicated enforcement authority and 85 of the 184 signatories do not have an enforcement authority at present. An Enforcement Fund will need to be created from the 1% import levy to major import markets. This Enforcement Fund can support the many signatory countries who lack the means to create such an enforcement authority.

- Create a Prosecution Fund For Wildlife Crime. A dedicated enforcement authority is only as useful if the country also has the ability to prosecute offenders. That means having strong laws on wildlife crime, tough sentences and the ability of prosecution services to bring cases to court, which requires funding for evidence collection and preparing cases. Again, the money would come from the import levy.

Only with such reform can CITES retain any form of relevance and credibility in line with its stated objective and primary vision for 2030.

In the end, CITES and the trade in all wild species must be moved to a foundation based on the precautionary principle, which should have been done decades ago. Only by implementing a reverse (positive) listing model for this trade can a precautionary principal approach be achieved. This will mean that the CITES convention itself will need to be opened up to a comprehensive review to enable its modernisation.

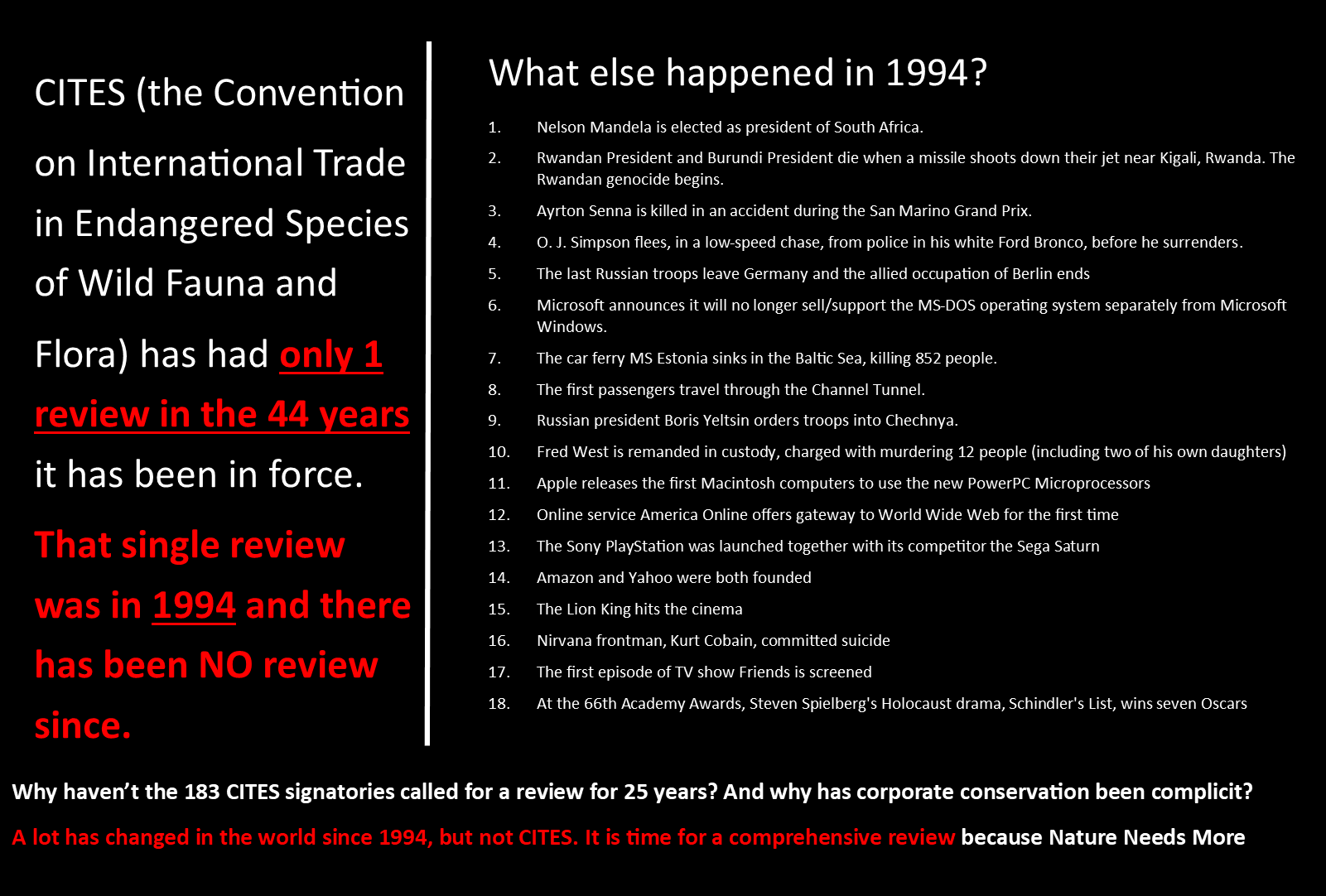

In its nearly 50-year history the CITES convention itself has had only one, narrow review in 1994. Many of the young conservationists participating in CITES CoP19 weren’t even born when this single review occurred. To help understand just how the world has changed since 1994, the following list outlines some key events and ‘placeholders’ that happened that year.

I don’t know of any organisation that can remain relevant without review. CITES and its signatories appear to be diverting attention away from a transparent review of the convention. Such a review was on the table at the last Conference of the Parties and then extensively discussed at the last Standing Committee meeting in Lyon earlier this year. The Standing Committee rejected the call for a review of the effectiveness of the convention citing two reasons – i) there is no money to conduct a review and ii) the internal CITES review mechanisms are working well.

This would be hilarious if it wasn’t so tragic. CITES can’t afford US$300-500K for a review but is supposedly effective? How can any regulator that has no money be effective? Starving a regulator of funds is a well-known strategy to produce regulatory failure (just ask the FAA and the victims of the Boeing 737 MAX disasters).

As for the internal review mechanisms, we mentioned Reviews of Significant Trade above. They do work but CITES only conducts a tiny number in each 2.5 year cycle between CoPs. Of those, about half are not even concluded or end without any resulting action. Certainly not a way to effectively regulate the trade in 38,500 species. Reviews of Significant Trade also suffer from the same iconic species bias as academic/NGO funding.

The notion that a comprehensive review is not needed must be challenged. The fact that the CITES convention itself has had just one review in its 50-years begs the question, what is the fear of a perfectly normal organisational process? That it will uncover that CITES is not fit for purpose? Much better to keep up the pretence that CITES is working and rely on the lack of interest from the general public and the mainstream media to maintain business-as-usual.

As I said, tragic.