In 2019, the IPBES confirmed that under the present socio-economic model one million species are threatened with extinction in the near future. Overexploitation for trade is one of the two key drivers of the current extinction crisis. As yet there is no evidence that the dual desires, to ‘supply for profit’ and ‘consume for status’, can be curbed. Groundhog Day on just one iconic species, elephants, shows how stuck human mindsets are.

One of the most contentious wildlife trades, debated over many decades, is trophy hunting. Earlier this year Botswana’s President Masisi was interviewed over his comment to send 20,000 elephants to Germany. The reason for the ‘offer/threat’ was that Germany’s environment ministry raised the possibility of stricter limits on the import of hunting trophies over poaching concerns.

This was indeed a worrying development for the global hunting industry, as Germany hosts Europe’s largest annual trophy hunting fair and is one of Europe’s top importing countries for hunting trophies. Hunters want ‘big game’ and elephants are the biggest game there is.

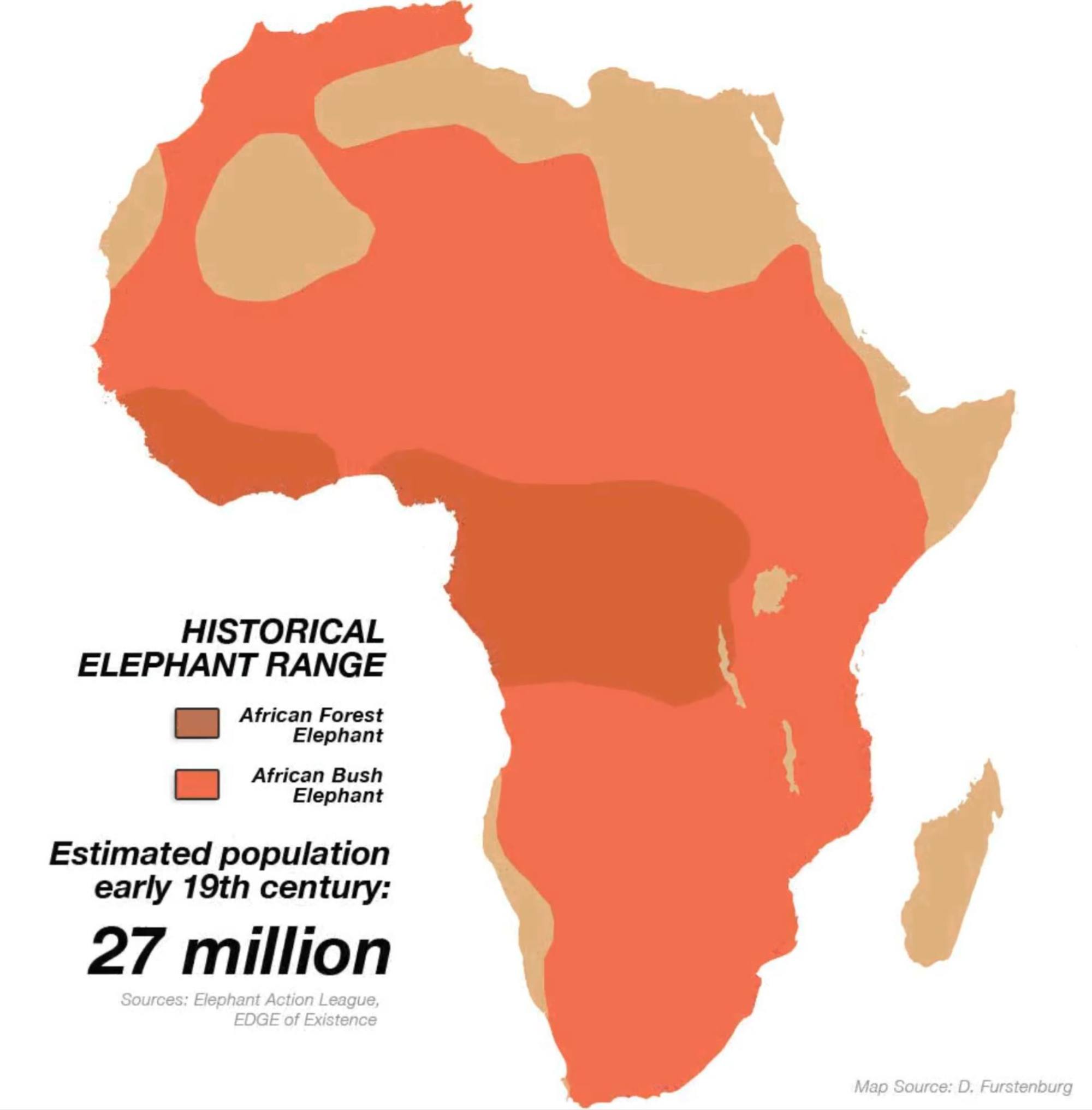

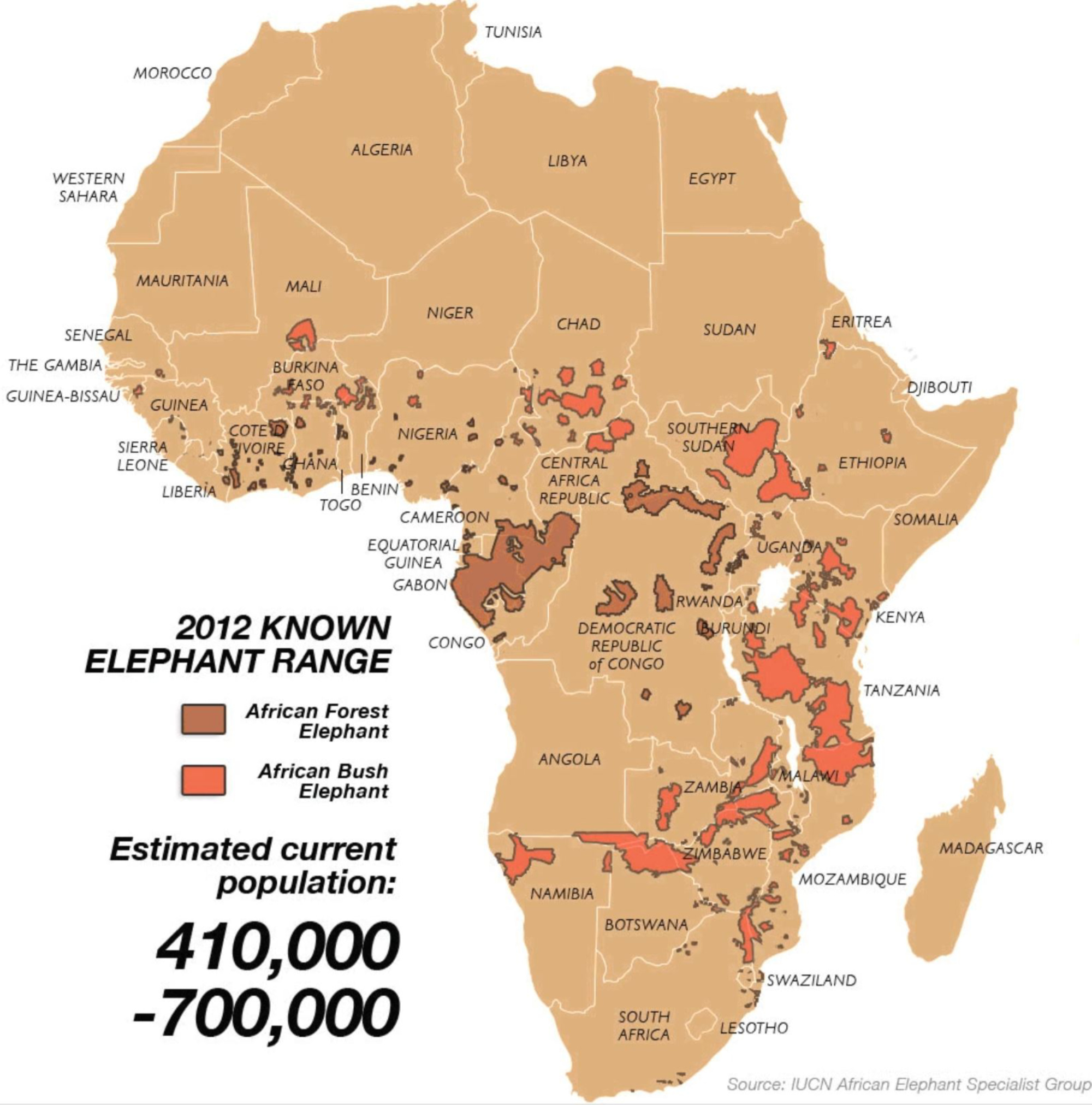

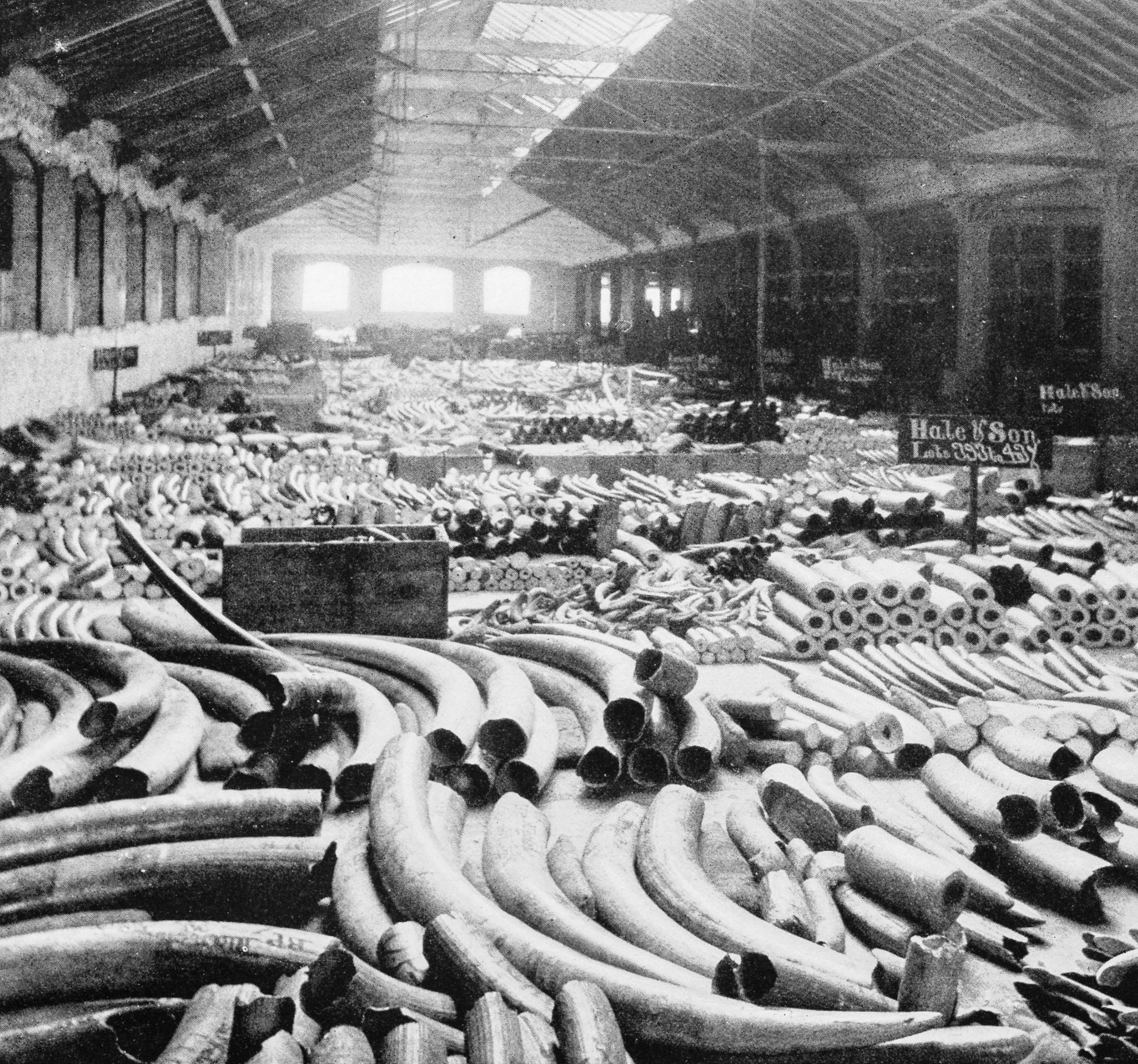

The desire to shoot elephants is not new. Hunting of elephants for sport, which was particularly excessive during the colonial period, with the British being the worst culprits, has played a significant role in the African elephant’s population crash over the last 200 years. The current estimate of the African elephant population is just 415,000, down from around 27 million in the early 19th century.

The scale of elephant annihilation is a result of too few people considering the words of Henry Beston, writer and pioneer of the modern environmental movement, who said, “The creatures with whom we share the planet and whom, in our arrogance, we wrongly patronize for being lesser forms, they are not brethren, they are not underlings, they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the Earth”.

Beston retreated into nature to recover from his traumatic experiences during WWI. He served as an ambulance driver including at The Battle of Verdun, which lasted for 302 days, one of the longest and costliest in human history. Immersing himself in nature to heal, he wrote, “Nature is part of our humanity, and without awareness of that divine mystery, man ceases to be man“. An insight certainly lost on the global hunting industry in its desire to profit from its clients’ fragile egos.

And so, with Germany’s announcement of the possibility of stricter limits on the import of hunting trophies the button was pushed on the ‘pro-trade’ PR machine (yet again). Conservation academics and NGOs, together with free trade advocates, opened their go-to playbook, outlining the need to manage human-elephant conflict, and rehashing the old talking points of ‘well managed’, ‘sustainable’ trophy hunting, ‘community benefits’ and the ‘conservation benefits’. Let’s just look at each of these.

Human-Wildlife Conflict#

Of course, President Maisi has a point when it comes to the difficulties of living near elephants. Botswana is ‘home to’ about 130,000 elephants (elephants migrate across borders if permitted), the largest population in Africa. That seems an awful lot, but it is also important to consider that Botswana is 50% larger than Germany in size yet has only 3% of Germany’s population. It is one of the most sparsely populated countries on earth. While human-elephant conflict does happen, was the push back on Germany’s proposed stricter limits really about the ‘threats’ posed by elephants to human populations and crops? As a recently published article pointed out, in this already sparsely populated country, “trophy hunting [in Botswana] generally takes place far from human settlements in remote photographic concessions”.

For the trophy hunting countries and industry, managing risk is a long way down the list that prioritises making money. Botswana is one of only a handful of countries in continental Africa that permits trophy hunting and whose elephant population is on Appendix II of CITES, which means it is possible to export hunting trophies without the need for a corresponding import permit in their destination country (unless the importing country demands one). And here we come to the illusion of a ‘well managed, sustainable trophy hunting industry’.

The ‘Well Managed’ Illusion #

How does an industry demonstrate it is well managed? Normally this would be by demonstrating the quality and completeness of its data. Any due diligence is fundamentally a record keeping and transparency issue. Data completeness and comprehensiveness is about it being robust at the most granular level, accessible, complete and free from contradictions; uniform data is needed to ensure any business or industry has a complete data set.

After what seems a lifetime of people supposedly being enthralled by wildlife documentaries, especially those about iconic endangered species, you would think that there would be a clear expectation that if these species were going to be killed for profit this trade would be diligently managed. This is not, and has never been, the case.

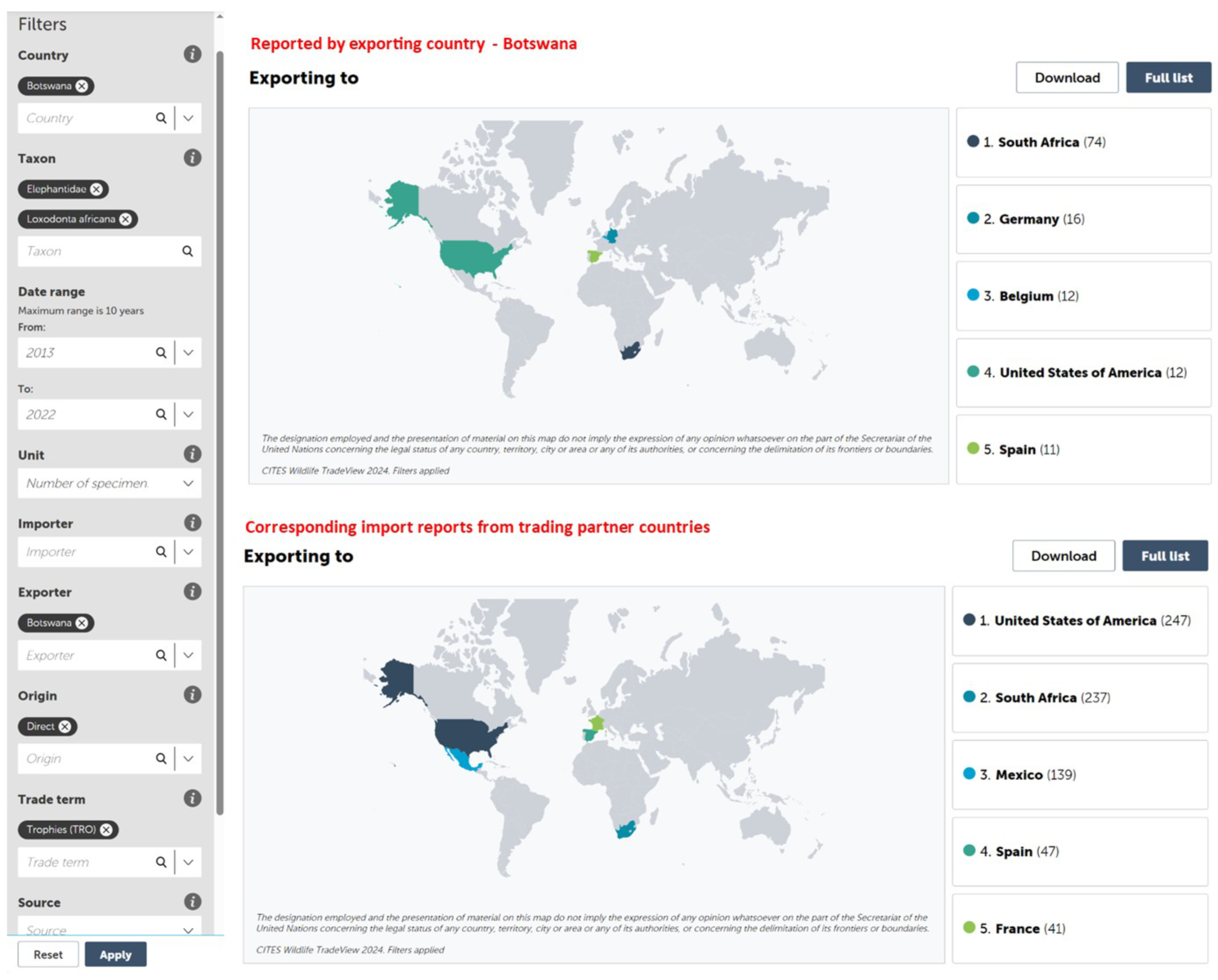

Using the CITES TradeView website to look at the trade in elephant trophies exported from Botswana between 2013 and 2022, nothing can be reconciled.

For example, during this time Botswana’s data documents exporting 12 elephant trophies to the USA, while the USA’s data documents 247 trophies coming from Botswana. While the absolute number of elephant trophies isn’t high (because it includes the years 2014 and 2019 when Botswana banned trophy hunting), the question has to be, when the numbers are so low, and elephants are considered so iconic and precious, why can’t the export/import data be reconciled?

If the CITES regulator can’t do it for elephant trophies, exported in the few hundreds every year, what chance do the species, exported for profit in the millions annually, stand to be well managed? Nothing about the CITES trade data can be described as quality, robust, complete at the most basic level let alone on a granular level. In its current state, CITES cannot prove the sustainability or legality of the trade in endangered and exotic wild species There is no such thing as a well-managed, sustainable trophy hunting industry, it simply doesn’t exist.

The trophy hunting industry is a wealthy industry, its customers are wealthy individuals, and this is a wealthy person’s ‘hobby’. Hunting permits for elephants cost thousands of dollars, the government and the businesses that sell hunting safaris stand to lose a lot of money if countries such as Germany make it harder to import trophies. Without the ability to bring the ‘trophy’ home big game hunting is of no interest to the vast majority of hunters.

Yet the many decades of Groundhog Days with the elephant trade have not led to this wealthy industry, or its wealthy customers, to show any interest in due diligence to improve the record keeping. Together with over 160 CITES signatories, both Botswana and Germany still use CITES 1970s paper permit system, which a number of CITES Secretary Generals have admitted is open to fraudulent use.

In September 2023, CITES Secretary-General Ivonne Higuero wrote, “Unfortunately, problems can arise with the use of paper documentation, including fraudulent use. Complications in keeping track of documents during issuance, transportation, and verification could result in forged paper documents. This may involve declaring false information, altering documents, reusing them, or even theft. There also have been cases where lost paper permits were used illegally due to delays in reporting and the extended duration of subsequent notifications among Parties.”.

When Nature Needs More started lobbying CITES signatories to implement electronic permits, in 2018, only 2 countries had upgraded their system from 1970s paper permits, now it is still only 19 countries worldwide. But it isn’t only the signatory countries who have shown little interest in solving the fatal flaw of the CITES paper permit system, conservation academics and NGOs who believe in trade have not lobbied to implement a modern, transparent, real-time trade system.

This is one of the reasons Nature Needs More was in Washington DC in October 2023, working with our US-based collaborative partner, Active for Animals, to meet with congress people and senators to lobby for the US government for a donation of less than US$12 million to roll out CITES ePermits throughout continental Africa. The USA, which has implemented CITES electronic permits, accounts for 71 percent of hunting trophies imports. The trophy hunting trade alone demonstrates that the US government needs to commit to ensuring ‘supply chain transparency’ for the industry serving the desires of mainly US-based hunters.

Since Tanzania has been in the news recently, for allowing the hunting of the remaining handful of ‘big-tuskers’ in continental Africa, it is also important to know the country still uses CITES 1970s paper permits. So too does Kenya, the darling of the conservation world.

To-date, only 3 countries in continental Africa have implemented a modern digital CITES trade permit system, that can be monitored in real-time, these countries are the DRC, Uganda and Mozambique.

There is no transparency in the CITES trade system. The number of investigations that show the massive discrepancies between CITES permit data and other trade data (e.g. from customs) is legendary. CITES has relied on an outdated permit and reporting system that was put in place 50 years ago.

As the Botswana elephant trophy hunting trade example shows, even for items that are easy to weigh and count, like elephant hunting trophies, the numbers can never be reconciled between hunting permits issued, trophies exported, and trophies imported.

While the proponents of trophy hunting haven’t invested in any due diligence and risk management for this trade, trophy hunters are well organised and well-resourced in pushing their pro-hunting agenda. They have spearheaded a long-standing push to portray trophy hunting a as valid conservation measure.

CITES fully buys into this story, Resolution Conf. 17.9 on the trade in hunting trophies states, “RECOGNIZING that well-managed and sustainable trophy hunting is consistent with and contributes to species conservation, as it provides both livelihood opportunities for rural communities and incentives for habitat conservation, and generates benefits which can be invested for conservation purposes”.

The ‘Sustainable Use Model’ Illusion

Setting to one side the community benefits illusion (as there is little evidence they exist in a meaningful sense), the question remains if trophy hunting is consistent with and contributes to species conservation. The claim that trophy hunting “provides … incentives for habitat conservation, and generates benefits which can be invested for conservation purposes” has no basis.

The phrase ‘which can’ does a lot of heavy lifting here. These benefits surely could be invested for conservation purposes, if they weren’t realised as private profits of the hunting operators and safari organisers. The Panama Papers exposed at least 30 companies offering safaris (not only hunting safaris), operating across southern and eastern Africa, from Namibia through Zimbabwe and Botswana up into Tanzania and Kenya, who preferred to move their profits offshore.

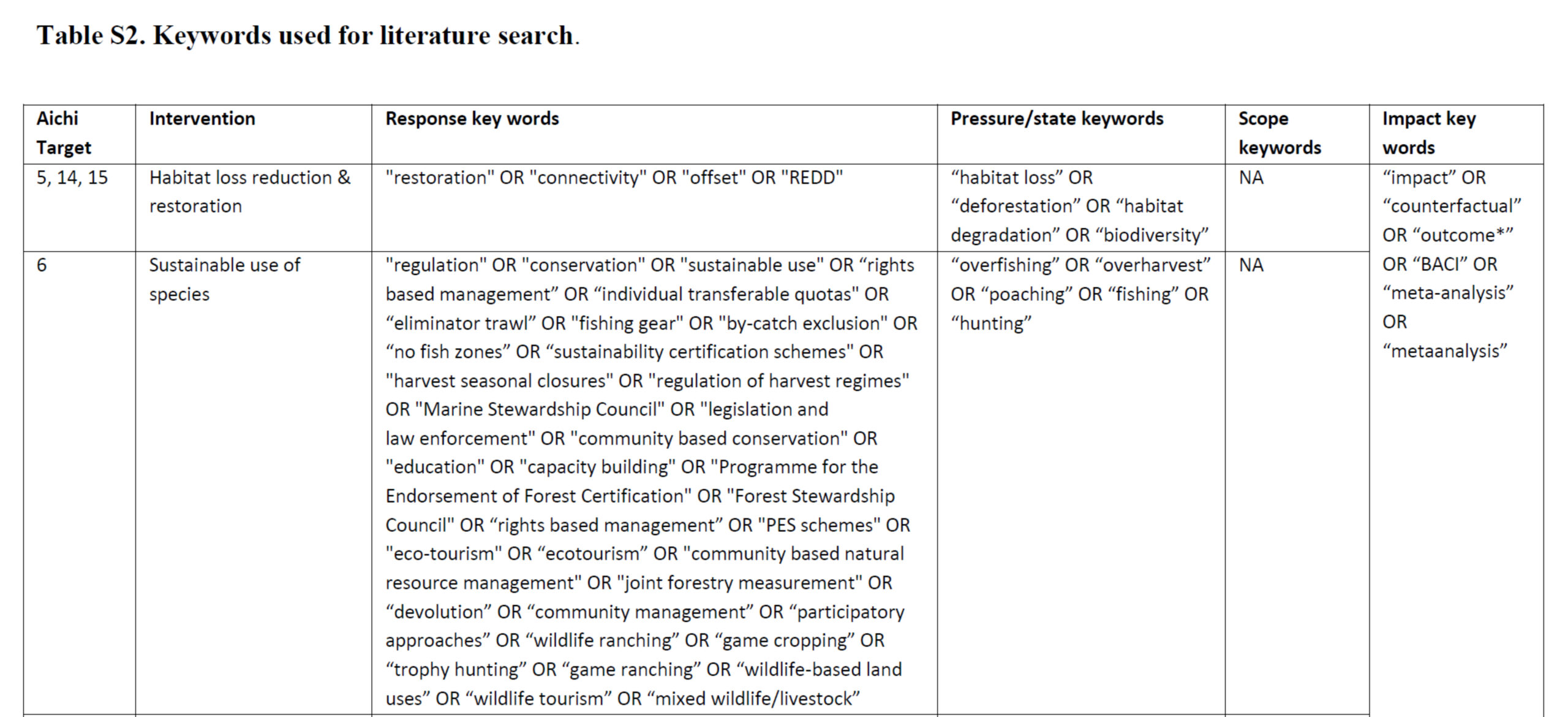

The trophy hunting trade is portrayed as an instance of ‘sustainable use’. Yet no proof of the sustainable use model as a valid conservation measure has ever been put forward. This was clarified (again) earlier this year in a new study, The Positive Impact Of Conservation Action. The paper, which had 33 authors, conducted a meta-analysis of scientific studies on the impact of conservation interventions.

Starting with a scan of over 30,000 potentially relevant publications, they found 186 studies evaluating the rate-of-change impact of conservation interventions globally over the past century. One type of conservation action they analysed was the sustainable use of species; yet the finding on the impact of sustainable use interventions was ‘inconclusive’. Why?

The major issue was that this meta-analysis could find only 5 publications related to the sustainable use of species that analysed the rate-of-change and a counterfactual to the intervention (meaning, that analysed the rate of change in the species population over a time period and compared this with a similar site where no conservation intervention was taking place) – just 5 publications! This is particularly surprising given several of the authors are big proponents of the sustainable use of wild species. Given how broad the keyword search was in the sustainable use of species category, compared to all the other categories, they tried very hard to find proof, but it simply didn’t exist.

The fact that this meta-analysis identified only 5 papers, out of a few thousand, that fit the search criteria is probably the worst indictment of sustainable use as a conservation measure you could possibly come up with. If nobody bothers to study it, it’s sure to have no merit, given that studies with negative findings are less likely to get published.

Three significant analyses of the sustainable use model have been undertaken in recent years, including one commissioned by CITES. None provided any proof that the sustainable use model was a valid conservation strategy. All demonstrated that the conservation benefit of the international trade is an illusion.

The ‘Conservation Benefits’ Illusion#

Maybe the debate around the ‘conservation benefit’ of hunting elephants for trophies would have a bit more substance if elephant populations were growing strongly in the countries that permit hunting, but that is not the case. Botswana’s elephant population has been stable since 2015, as it has been in the overall Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (known as KAZA), which stretches across:

- Botswana (which still uses CITES 1970s paper permits),

- Namibia (which still uses CITES 1970s paper permits),

- Zimbabwe (which still uses CITES 1970s paper permits),

- Angola (which still uses CITES 1970s paper permits) and

- Zambia (which still uses CITES 1970s paper permits).

More than half the world’s savannah elephants live in the KAZA area and all KAZA countries allow the trophy hunting of elephants.

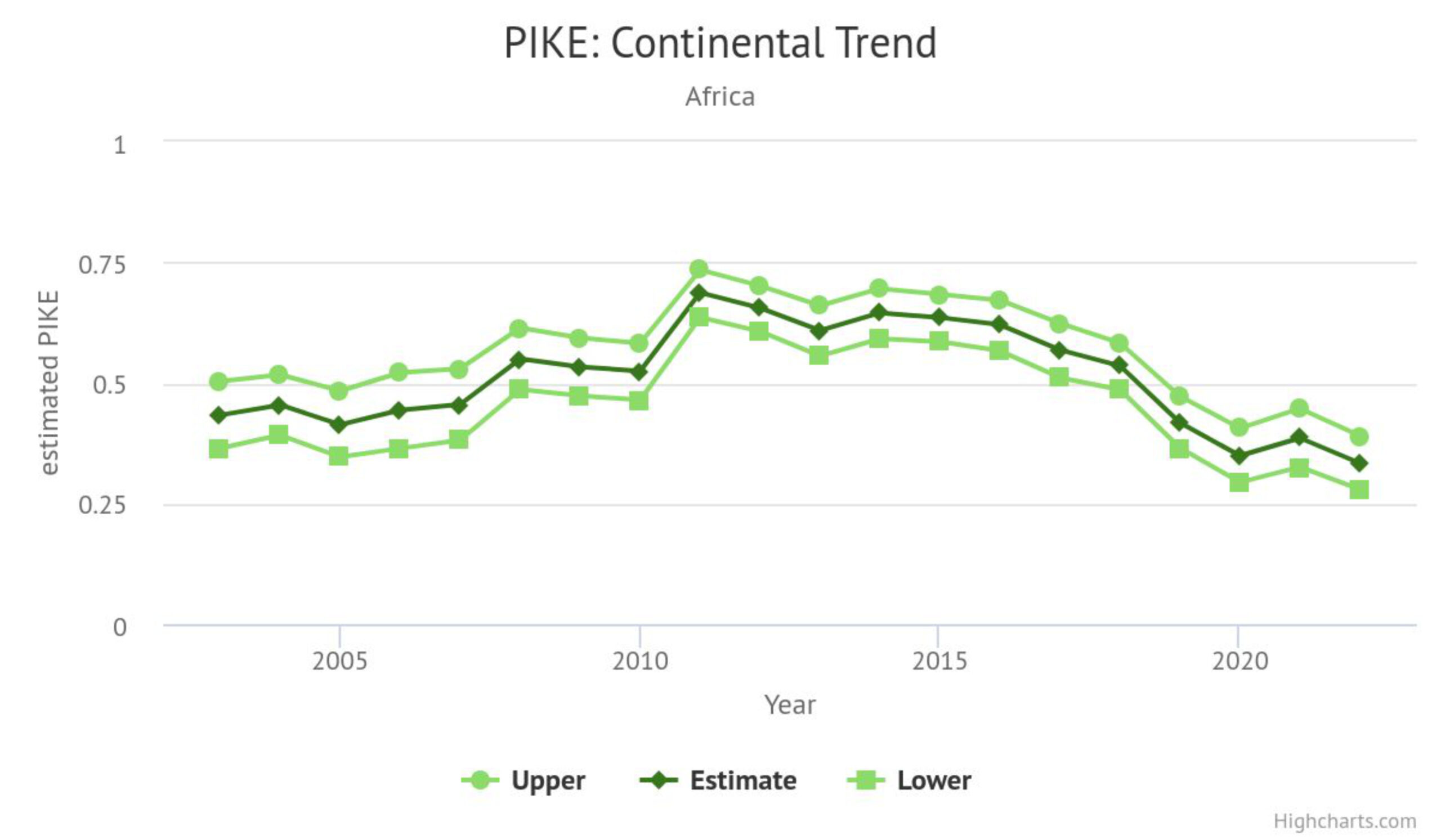

Poaching of elephants for their tusks is of course the major issue for elephant populations, but poaching has fallen substantially in the last 10 years, as can be seen from the MIKE data, with carcasses attributed to poaching falling from 70% in 2011 to 35% in 2022.

Despite the evidence to the contrary, trophy hunting organisations and the not-so-small number of conservation agencies that have bought into the line that “well-managed and sustainable trophy hunting is consistent with and contributes to species conservation” will continue to go along with the deception.

For the pro-hunting camp, it is in their best financial interest to do so. The conservation NGOs that buy into this are probably concerned about funding from pro-hunting/free-trade governments and rich donors committed to the neoliberal ideology.

So, they restrict themselves to complaining about the fact that most trophy hunting is ‘not well-managed’ (which is well-established) but turn a blind eye to the very idea of legalised killing of wild, endangered species for ‘sport’.

Time To Decide ‘Big Game’ Or ‘Sentient Beings’#

There is ample research confirming that elephants are amazing, sentient beings. People often feel an emotional pull towards being with them, some even regard it as a spiritual experience. It should come as no surprise then that scientists have recently established that elephants call each other by name. They recognize each other as individuals and feel the loss when someone is killed; they know who is here and who is gone. Shouldn’t that finally be enough to give elephants legal personhood?

Even without the scientific research, it is obvious that elephants don’t want to be killed. Botswana reintroduced trophy hunting in 2019. Comparing numbers from Botswana’s 2018 survey of elephants against the 2022 KAZA Elephant Survey, Elephants Without Borders found that elephant numbers had decreased by 25% in areas open to hunting — and increased by 28% in areas where hunting isn’t allowed.

Clearly, elephants know better what’s good for elephants than conservation organisations and academics who support hunting!

Big-game hunting is an archaic ‘sport’ practiced by a tiny number of rich people from a tiny number of countries. Modern big-game hunting has nothing to do with skill, the hunter usually selects the trophy prior to setting off on their safari, trackers then find the target. The header image for this article was taken during a photographic walking safari, skilled guides get people this close to wildlife every day. For the hunter, the ‘skill of the kill’ is equivalent to hitting at a parked car from close range. Some hunters are even dumb enough to confirm that they shot from a truck. Given all wild species, including elephants, become habituated to trucks due to the proliferation of photo safaris, any shooting from a truck is equivalent to shooting fish in a barrel.

Even the guides don’t speak well of hunters, admitting in conversations they prefer Americans, saying “I don’t like working with Germans, too often they are cruel to the animals” or “my least favourite group to work with are the Russian hunters, they just drink and bring prostitutes”; hardly ringing endorsements of clients. And local community groups have voiced their concerns about the indiscriminate killing of wildlife. As recently reported, in Mongabay, “local leader revealed that foreign hunters used semiautomatic weapons to indiscriminately kill wildlife. Maasai herders have long been responsible stewards of the land, coexisting with wildlife, they said”.

But the tragic mess, that is the decades of Groundhog Days for the elephant trade, doesn’t only lay at the feet of the trophy hunting industry and pro trophy hunting countries.

In 2018, a joint parliamentary inquiry into the domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn confirmed that, given there are no laws preventing the sale of ivory and rhino horn being bought and sold once it was illegally brought into Australia. The inquiry concluded this domestic trade was helping to drive poaching and resulted in bipartisan support to close the domestic trade.

In 2019, at CITES CoP18, Australia formally announced its intention to close the domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn. Five years on this still hasn’t happened. Why?

In the same way Germany’s announcement of stricter limits on the import of hunting trophies, the button was pushed on the ‘pro-trade’ PR machine (again). In this instance it was the antiques industry together with pro-trade conservation academics and NGOs. So, the federal government put it in the too-hard basket and the new government followed suit and broke its election promise.

It is high time to stop the tiny number of people who crave hunting trophies or ivory carvings to be able to dictate the agenda of public policy.

For the global majority who see elephants as sentient beings deserving our protection and respect, it is time to stop getting distracted with the pro-hunting and pro-trade talking points which have no basis in reality. It is especially time to demand conservation NGOs stop buying into these talking points, creating studies muddied by commercial interests and take a resolute stand against trophy hunting.