Out Today: New Nature Needs More Report

Modernising CITES – A Blueprint for Better Trade Regulation. The report outlines a comprehensive strategy for regulating the trade in all species of wild flora and fauna.

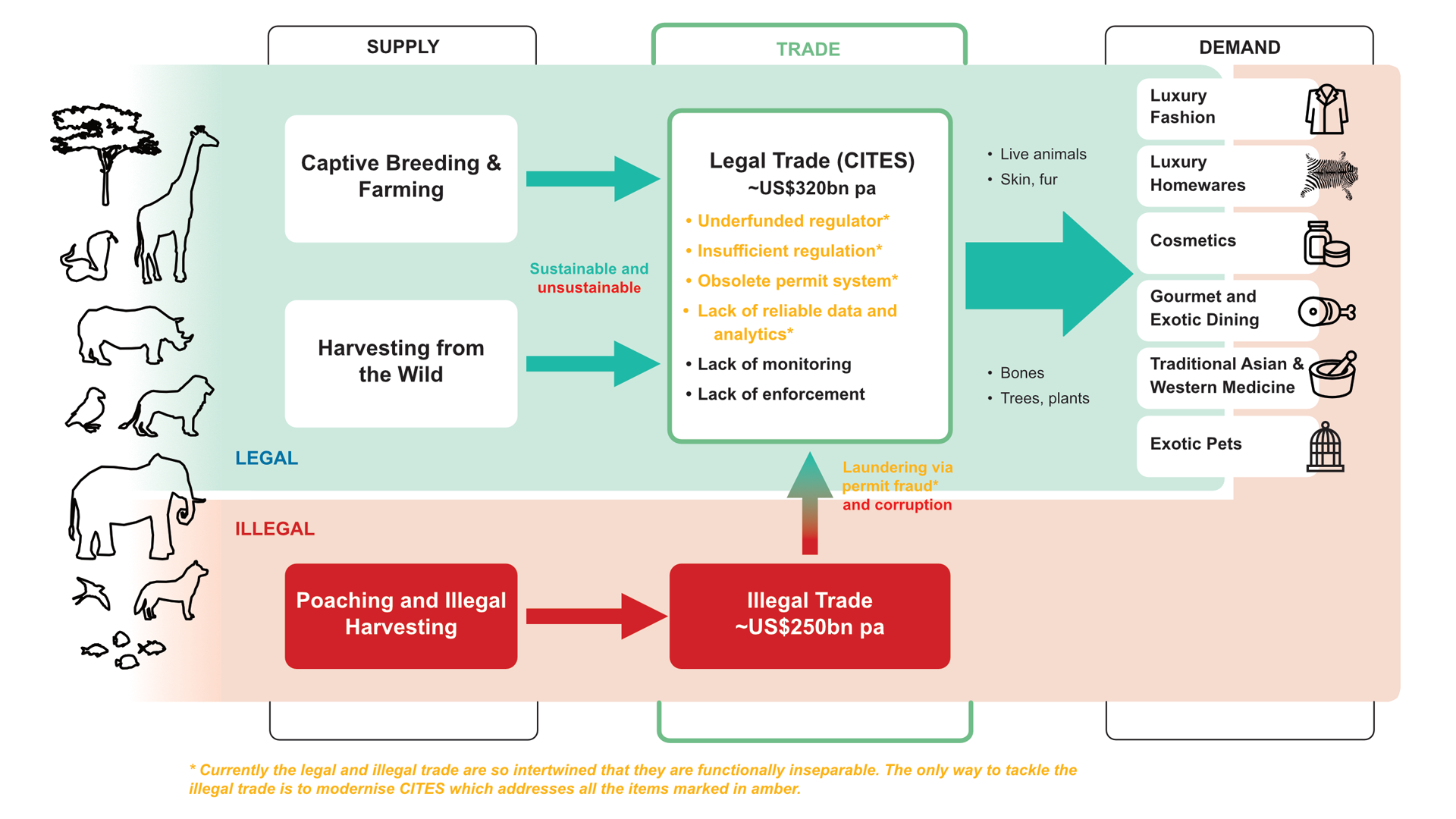

CITES has failed in its stated objective of protecting endangered species from over exploitation from the legal trade, with trade being the primary extinction driver for marine species and the second most important driver for terrestrial and freshwater species. Whilst the lack of funding to enforce CITES provisions has long been known as a key reason for this, blaming the illegal trade is a convenient excuse to ignore the crucial design flaws in the current CITES model.

Since the release of our Debunking Sustainable Use Report, which outlined that without supply chain transparency there is no proof of the sustainable use model, we decided to fully investigate the reasons why CITES is failing.

We researched regulatory models in other industries and the history of regulatory failures to draw conclusions about the suitability of the basic building blocks of the current CITES framework – blacklisting, national sovereignty and it being a non-self-executing treaty. We demonstrate that with those basic building blocks remaining in place, CITES cannot be effective and cannot arrest the decline in populations.

The report outlines a new regulatory framework for CITES based on whitelisting, regulating business directly and businesses paying the full cost of regulation. The model we present makes business responsible for internalising compliance yet keeps companies at arm’s length from the regulator and the regulatory process. We offer a detailed account of how this model would work in practice, under real world conditions. We show that it is financially viable, providing US$9-13.5 BILLION annually to regulate, manage, monitor and enforce the legal trade. Finally, we offer a path for CITES signatory countries to make it happen, acknowledging the difficulty involved in opening the articles for re-negotiation.

But this isn’t only about a rational argument for a long overdue change, the report also stimulates discussions on the wider context and the roadblocks to change. It is a sobering thought that more people find it easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Maybe this isn’t so surprising when you see the level of protection to profits and investments built into international governance. These protections stand in the way of any modernisation to deal with a changing world context, from biodiversity loss to global warming.

Treaties, conventions and national laws need to be urgently modernised and strengthened to protect the most vulnerable and the planet, but business and investor interests currently takes precedence.

This situation has been consolidated over the last 40 years, as the world has been conditioned to see that all regulation is bad. Instead, we have been led to believe that voluntary commitments, self-regulation and multi-stakeholder initiatives will protect the most vulnerable from the powerful economic actors who, behind the scenes, lobby to stymie progressive policies that may impede their profits.

The evidence indicates that most multi-stakeholder initiatives have adopted the same set of self-interested dynamics of corporations and their investors. If they are global, they are even less democratically accountable than their domestic counterparts; it is only those who can afford a seat that the table that have a voice. As a result, powerful players, who appear to lack concern for any form of environmental protections, have more access to shaping treaties or too much influence developing the positions that governments take internationally. As corporations, industries and investors stand in the way of international governance, challenging international laws and treaties that are there to keep their exploitation behaviour in check, environmental and social justice are the losers. Only the agreements protecting trade and investment are well resourced and well enforced.

Conversely those focused on the environment, such as CITES, receive limited resources, limited political attention and limited political commitment, to the point they are so impoverished they become meaningless and useless. Instead, the now widespread Investor-State Dispute Settlement system allows companies to sue countries who strengthen domestic regulations to protect the environment. Investment arbitration firms bring claims against countries for loss of profits for investments in those countries, if regulatory standards are strengthened and could impact future profits. An example of this is playing out in Europe right now, with German energy giant RWE using the Energy Charter Treaty to claim compensation from the Netherlands over its planned phase-out of coal from the country’s electricity mix by 2030.

It is in this context that we present our case for modernising CITES. Biodiversity loss is an international governance challenge, not an issue of more evidence-based science being needed. Our proposal will undoubtedly reduce the mindboggling profits that have been made by businesses and investors from the trade in endangered species for the last several decades. They have had plenty of time to invest in improving supply chain transparency and sustainability, yet they have done nothing. All the evidence shows voluntary self-regulation by business rarely works. It is time to modernise and invest in independent global regulators to help save the little that is left.

Will we continue to let corporations and investors stand in the way of modernising international governance? If there is no transformation to a regulatory framework that can deal with both the current and future level of commercialisation of species, then the only remaining step would be a total trade ban. It is time for these powerful economic actors to accept that without transparency there can be no trade.

The report is currently only available in English. We are in the process of raising the funds to have it translated into all UN languages – French, Spanish, Russian, Mandarin and Arabic.

For more information about the report, please contact Lynn Johnson: lynn@natureneedsmore.org