As many of Nature Needs More’s supporters know, we are concerned about the systemic flaws in the CITES trade permit and monitoring system and, together with For the Love of Wildlife we have suggested a reverse-listing and legal trade levy solution to fix these longstanding flaws and provide the necessary level of resourcing to ensure the system is fit for purpose.

But while we work for the CITES system to be fixed, other groups push for loosening of trade restrictions in animal body parts. As they continue their lobbying to further liberalise trade, in recent times they have moved towards using the plight of impoverished communities that border key wildlife populations. I would like to explore this latest ‘argument’ for yet more trade in flora and fauna in this blog.

As a reminder of the scale of the legal trade, I include the same image I have used before, because even after looking at these figures for many months now I still find these amounts astonishing.

While Nature Needs More believes to protect the natural world, we need to move from a trade-based convention to a conservation-based one, this will not happen in the short term. For now, we ask CITES signatories to fix the existing trade and permit system.

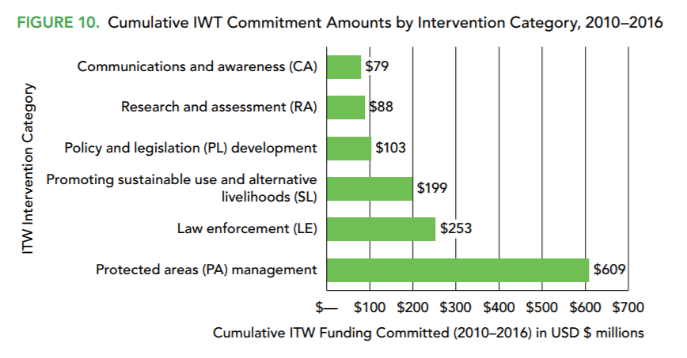

The first step would be to finally implement the global e-permit system they have been talking about for a decade. We know that this would not be cheap, but it is vital given the sustainable-use model appears to be what world governments and conservation agencies (over) rely on. For example, a World Bank Report highlighted that nearly US$200Million was spent promoting sustainable use and alternative livelihoods, yet no investment has been made to implement the worldwide e-permit system to manage the trade they are investing in driving up.

And it is not a surprise that governments around the world are driving up trade when you read reports such as this one from the European Parliament. This huge and wealthy region of the world, which buys about a third of the world luxury goods, is very upfront about the value of the legal trade in wildlife to the region; the first line of the document states “The wildlife trade is one of the most lucrative trades in the world. The legal trade into the EU alone is worth EUR 100 billion annually”:

So, we must not be naïve about what is happening in the global trade of flora and fauna. While we work for better governance, resourcing and the need to tighten trade, there are others working towards making the international trade in animal body parts even easier that it already appears to be.

A January 2019 article, Southern Africa Should Refuse To Enforce CITES Failed Policies, highlights some of the more recent pro-trade arguments used in an effort to loosen trade regulations. The focus, which is being used more-and-more by people and groups wanting to liberalise trade, is the plight of rural communities not benefiting from their wildlife. From the linked article I take two typical statements:

“The frustration is most palpable where rural communities pay the costs of living with wild animals without realising any of the benefits.”

“Worse, the trade ban in elephant ivory and rhino products imposed at the insistence of the animal rights groups [has] eliminated local communities’ benefits from wildlife.”

Yes, you read that correctly it seems like poverty in rural Southern Africa has been created by Animal Rights Groups. Mmmmm, now I know we live in a world where facts have gone out of fashion, but this is pushing it a bit! So, let’s dig into this some more; if Southern Africa genuinely wanted to tackle the scourge of rural poverty there is a lot more that could be done to support these impoverished communities before selling off the region’s wildlife.

Distribution of Wealth – Gini Coefficient#

Southern Africa and incidentally the 3 countries calling for more trade, South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, are the 3 LEAST equal countries in the world.

It gets worse when looking at the top 10% and bottom 10% shares (from a Business Insider article)

Another example of South Africa’s level of inequity is CEOs earnings. The best and worst countries to be a rich CEO, South African CEOs earn 541 times the average income, compared with USA 299x, UK 229x, Switzerland 179x, Germany 176x

Point 1: If Southern Africa was genuinely concerned about rural poverty, then before selling off the regions wildlife heritage to help poor communities it could first focus on redistributing its current wealth more equally, so it stops being the least equal region of the world. Something to think about!

Trophy Hunting Industry Transparency and Economic Benefits for Conservation and Tackling Poverty. #

While point 1 tackles the whole economy in Southern Africa, with point 2 let’s explore a specific industry, trophy hunting. While many note the lack of transparency and the difficulty in getting clarity of the financial benefits of trophy hunting to conservation and rural communities, a report titled The Lion’s Share prepared by Economists at Large concluded that the marginal economic contribution of trophy hunting is likely to range between zero and $USD 132 million, depending on the alternative uses of land and wildlife resources; and not higher as stated in a report by Southwick Associates, which was commissioned by the Safari Club International Foundation.

The Economists at Large report also assessed that trophy hunting activities generates between 7,500 and 15,500 jobs and not the 53,400 job reported by the Southwick report; and highlights that the Southwick study is cautious not to claim a direct link between trophy hunting and wildlife conservation, offering a rough estimate that only between US$ 27 and 40 million potentially contribute to funding conservation in the eight study countries. If we take the top end – the US$40 million figure averaged over 8 countries means trophy hunting generates US$5 million per country.

Point 2: Trophy Hunting is not the economic or conservation power house the hunting organisations likes to project it is. If the trophy hunting industry disagrees with the figures in The Lion’s Share report prepared by Economists at Large then all they have to do is ensure that their industry is more transparent about how much is earnt and where the money goes. Simple.

But is it not only about what they earn, it is also about where the money ends up.

African Safari Companies and Tax Havens #

The 2015 Panama Papers, leaked by an anonymous source, highlighted that at least 30 wildlife safari companies in Africa were connected to offshore companies, mostly incorporated in the British Virgin Islands:

Point 3: Maybe anyone who will financially benefit from and who wants a liberalisation of the international trade in say elephant or rhino body parts (and flora & fauna more broadly) should be demonstrating that they are keeping all their money on shore?

If they use the excuse that they are sending their money offshore because of the corrupt government systems in their countries, then what are they doing to invest in educating a new generation who want to stabilise their own countries and build fairer democracies? Again, maybe they should work on this first before they push for more trade in wildlife body parts?

But it is unfair to burden the African continent to take on the governments and industries created to support capital flight and tax evasion. While this issue impacts us all and globally it is imperative to tackle this problem, it is useful to understand how secrecy jurisdictions have kept regions including sub-Saharan Africa unnecessarily impoverished.

Deal with Capital Flight and Tax Evasion#

A 2017 documentary: The Spider’s Web: Britain’s Second Empire is a must watch for anyone who cares about the lack of funding going in to sub-Saharan Africa to take care of its unique wildlife (as well as the continent’s people).

As it highlights, in the 1960s (what it calls the twilight years of British Empire) bankers, lawyers and accountants from the City of London travelled to the likes of the Cayman Islands to draft financial secrecy laws and regulations; setting up secrecy jurisdictions (tax havens) for individuals and corporations. As much as half of global offshore wealth is held in British secrecy jurisdictions.

The documentary singles out sub-Saharan Africa to highlight the impact of secrecy jurisdictions in plundering developing countries and regions. It states that:

- By the end of 2008, the combined external debt of sub-Saharan African countries was US$177 Billion,

- While between 1970 and 2008 the (capital flight and tax evasion) outflows from 33 sub-Sharan countries totalled US$944 Billion. (And we can only imagine the scale of capital flight and tax evasion since 2008!)

- So instead of being a net debtor to the world, sub-Saharan Africa has been a net creditor, over this timeframe, given the scale of capital flight and tax evasion that has flowed to the tax havens created by the West. Globally it is estimated that over US$1 Trillion pa in capital flight and tax evasion flows out of developing countries.

Point 4: Before more exploitation of the natural world is proposed as a way to solve rural poverty in developing countries maybe it is time to challenge the wealthy Western countries to deal with their secrecy jurisdictions. While some work has been done to look at the banking systems in these countries, little has been done to reveal the ultimate beneficiary owners of trusts.

While most of this blog post highlights if the pro-traders have a valid argument in talking about tackling rural poverty by liberalising the trading in animal body parts, I don’t want to ignore the other example used in the article to try to justify Southern Africa challenging CITES trade restrictions, namely Japan’s withdrawal from the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

Japan and the International Whaling Commission #

From the article: The countries of SADC should take the Japanese example to heart — declaring now that if CITES votes to enforce policies that individual SADC countries deem to have failed its wildlife, rural populations or national interests – they will in response refuse to abide by such harmful decisions… Responding to this danger, the world’s largest rhino breeder, South Africa-based John Hume said: “At a certain point, sovereign countries need to do as Japan did to the IWC; ditch conservation partnerships that do not benefit their wildlife and the people.”

Despite what John Hume implies with his statement, Japan was not thinking about whale conservation when deciding to leave the IWC.

From a conservation perspective: With its decision to leave the IWC, Japan loses access to the Southern Ocean where it used to conduct its ‘scientific’ whaling. Instead, it can now only whale in its own Exclusive Economic Zone, where the whale population has not recovered, and as such whaling will be very bad for conservation of the local whale population.

From an economic perspective: A 2012 report: The Economics of Japanese Whaling: A Collapsing Industry Burdens Taxpayers illustrates how taxpayers subsidise the money-losing industry. The whaling industry receives subsidies of around ¥782 million (US$9.78 million) annually and despite these subsidies, continues to operate at a loss. Over the past 25 years, direct whaling subsidies from the Ministry of Agriculture alone have cost Japanese taxpayers more than ¥30 billion (almost US$400 million). Restricting whaling to its local waters will reduce government subsidies.

From a political perspective: In addition, Japan is frustrated with the inability to negotiate access to international waters for fishing purposes; something that has been ongoing for many decades and goes back as far as the end of WW2.

Point 5: Japan pulling out of the IWC cannot be portrayed as a ‘better way’ to conserve ‘their’ whales, it does exactly the opposite and puts them under greater threat. It may indeed benefit ‘the people’, by reducing government subsidies, but this in no way applies to e.g. South Africa leaving CITES.

Conclusion#

Pro-trade groups have been lobbying for years now to further liberalise the trade in flora and fauna. Rather than one ideology against another, we must ask them for the specific details of their solutions, especially where they claim that the loosening of trade restrictions on animal body parts will drive conservation outcomes. How specifically do they back up such claims and what will they do if they are wrong and have opened Pandora’s Box? I leave you with one final thought: