From fins to teeth, skin and meat, the market for shark body parts is a grave concern, with shark finning being the most contentious issue.

The coverage of CITES CoP19 in the mainstream media has been thin on the ground, but one decision which did get attention was to list all 54 species of requiem sharks and hammerhead sharks on CITES Appendix II. Whilst this is undoubtedly good news that more sharks have received trade related protections, what will this mean in reality? Is this historic decision just a protection on paper?

Sharks are under serious threat from overfishing with 37% of shark and ray species facing extinction. Given the lack of national and international fisheries management, it would seem that listing sharks and rays on CITES Appendix II should provide protection in line with the stated objective of the convention.

But what these ‘protections’ are worth in the real world is a different matter and that is especially true for heavily exploited marine species. Maybe the best way to understand what these protections can do in the real world is to look at CITES trade data for shark and ray species already listed for trade restrictions under the convention.

This is the investigation Nature Needs More decided to undertake. So what did we do?

- For species listed for more than 10 years, we looked at the trade data between 2011 and 2020.

- For species listed more recently, for example the Silky Shark, which was listed in 2017, we looked at the trade data available from the year it was listed, and permit information collected.

- For the investigation we used the CITES TradeView website: CITES Wildlife TradeView

- The units used for the search were number of specimen and trade by weight (Kg).

- We looked at the top exporting countries and importing countries for each listed species.

- In most instance where trade was significant, we looked at the trade information for the top exporter and tried to reconcile the export/import data of the top exporter with the country listed as its most significant import partner.

In theory, what is reported by exporting countries and importing countries should match for ‘direct’ trade (trade without the involvement of transit countries which are classed as re-exports under CITES).

In practice, the picture is far more complicated. CITES does not mandate units, so the trade in sharks and shark fins can be reported in either ‘number of specimens’ or in kg. A trade permit made out in number of specimens by the exporting country may be reported in kg by the importing country and vice versa. Also, import reporting is not mandatory under CITES for Appendix II listed species.

All this means is that trade data in the CITES trade database are almost useless for the purposes of tracking and monitoring the trade. They are at best indicative. This can clearly be seen from just looking at a handful of sharks that are in dire need of proper protection from overexploitation.

Here are examples of the findings.

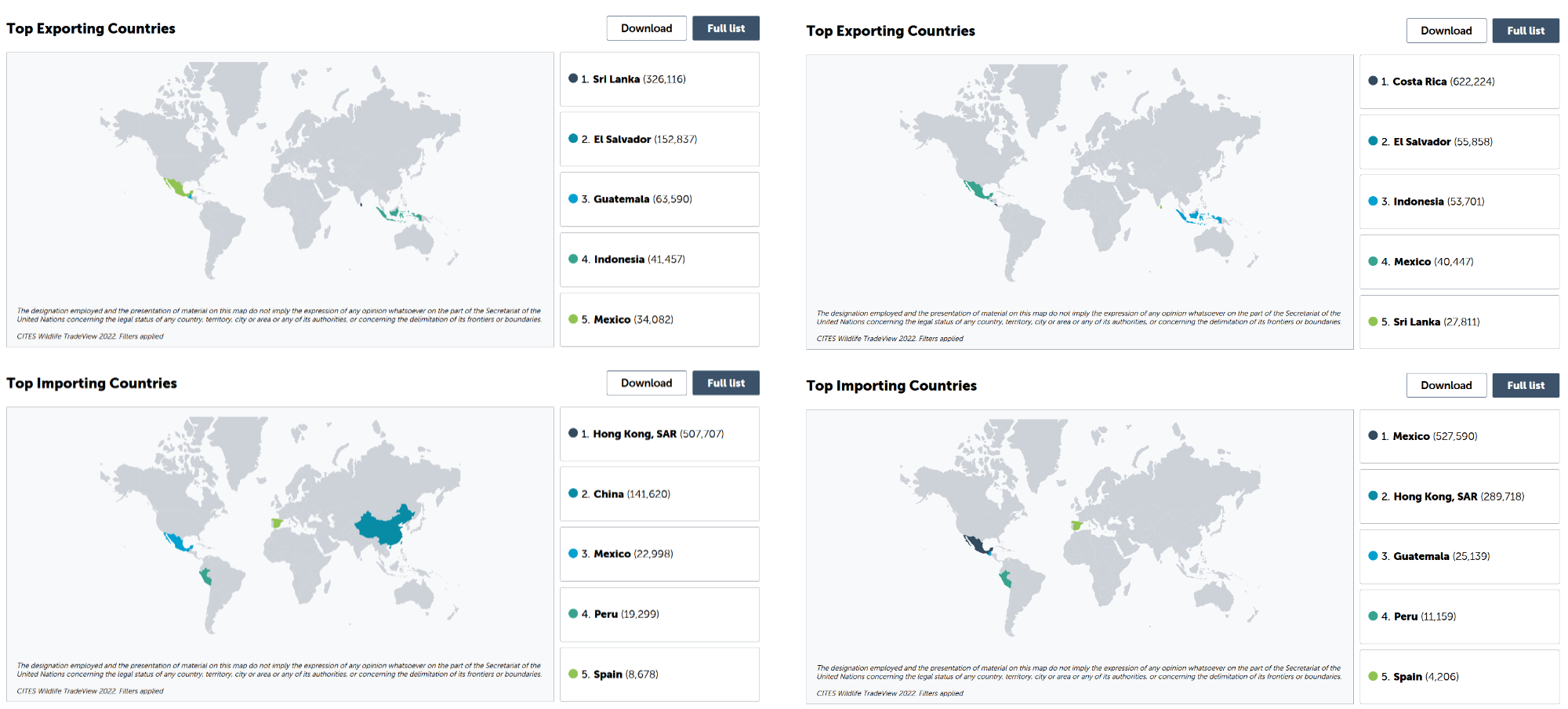

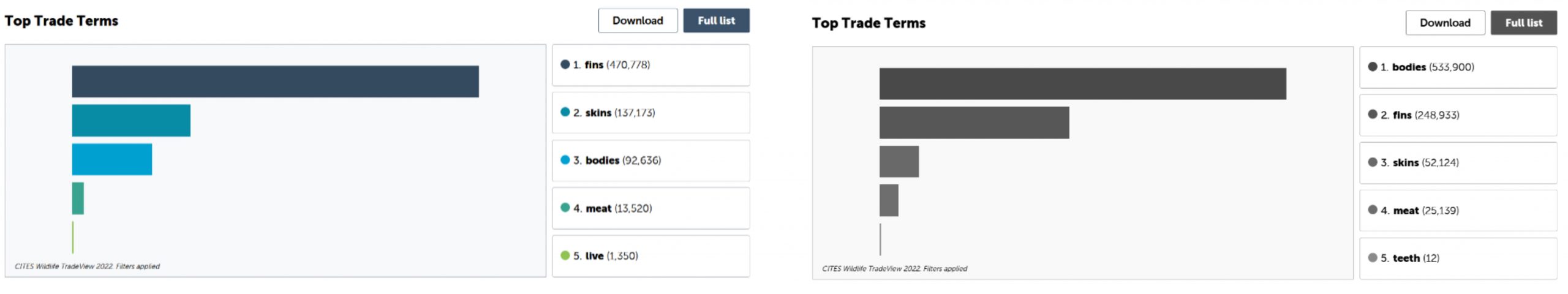

Most of the trade in silky sharks is recorded in kg, so we will look at the weight-based records for 2017-2022 first:

On the left are the quantities reported by the exporting countries and on the right the corresponding quantities as reported by the importing countries. What is immediately obvious is that the records don’t match, so we have no real idea about the magnitude of the trade between countries.

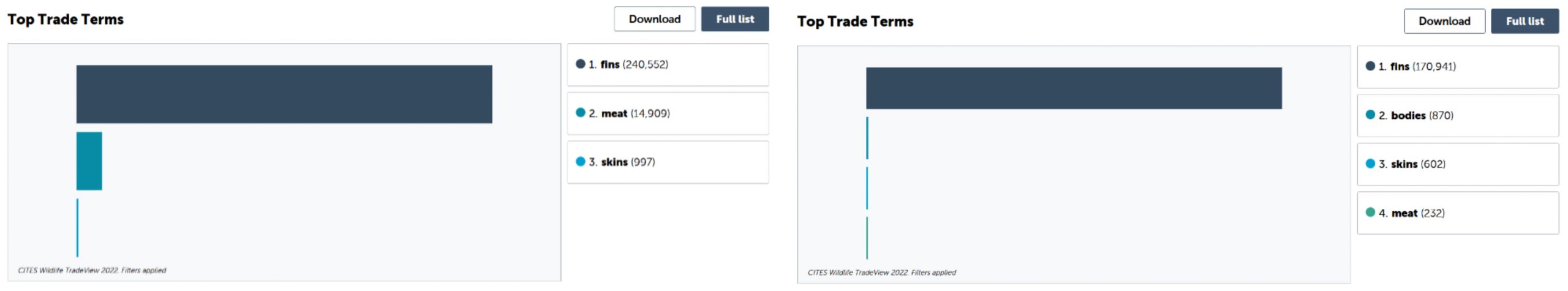

Poor reporting practices also lead to vast mismatches between the ‘trade terms’, i.e. what is being reported as being shipped.

Whilst exporters claim to be exporting predominantly fins, importers overwhelmingly report bodies. This distinction is not a trivial problem, in fact it is of utmost significance. If you are shipping 470 tons of dried fins, that is very different from shipping 533 tons of bodies.

If we assume the average silky shark weighs around 250kg, then the 533 tons of bodies reported would translate into around 2,000 sharks. The fin weight to body weight ratio differs for different shark species but will be somewhere in the 2-6% range for most sharks. If we use 5%, then the fin weight of the silky shark would be 12.5kg. That means that 470 tons of fins would actually translate into 37,600 sharks, which is a very different proposition to 2,000 sharks. The picture would get even worse if we consider that fins are likely shipped dried, so weigh even less.

Adding in the trade records with ‘number of specimens’ as the unit makes the picture worse, not better. Exporters report an additional 67,783 fins whereas importers record only 361 fins for the same 5-year period. This sort of mismatch turns CITES trade reporting into a farce.

It is really important to pause at this point and to ask “What can we ACTUALLY learn from these trade data?”. If we cannot tell if these bodies or fins come from 2,000 sharks or 37,600 sharks or even 50,000 sharks, what use is it to analyse the trade data? What purpose does CITES reporting actually serve other than complying with the paper-terms of the convention? Where is the conservation and protection benefit for the species?

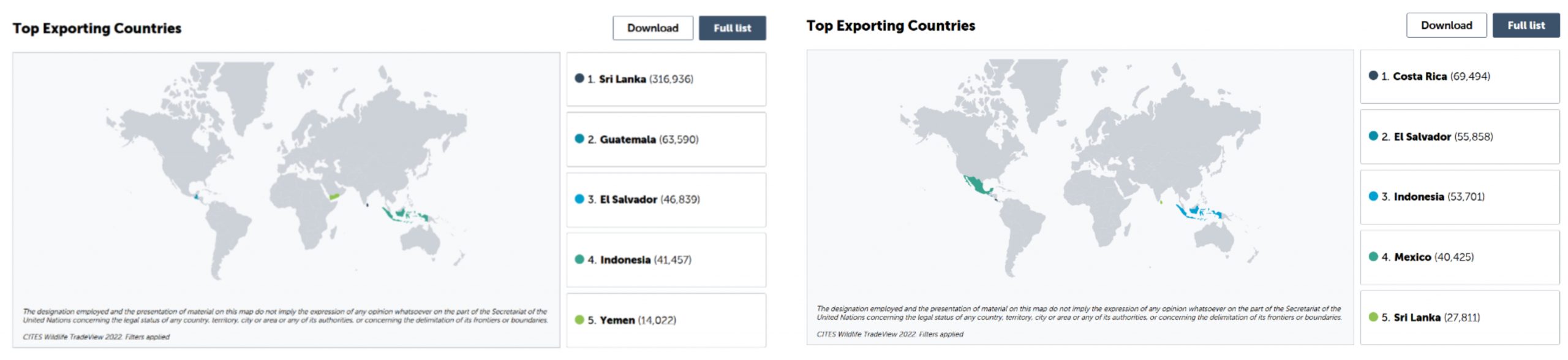

Given that it is well known that most of the shark fin trade goes to China via Hong Kong, we should take a closer look at how the trade to HK is reported in kg:

Sri Lanka claims to be exporting 317 tons of silky shark to HK whereas Hong Kong claims to be receiving just 28 tons. On the other hand HK states it received 69.5 tons from Costa Rica, which does not report enough trade to HK to even feature in the top 5 list. Given that these records are for direct trade, that is without involving a transit country, they should match.

Obviously drawing conclusions from just one species of sharks would be premature, so we will look at another species that receives a lot of attention, the endangered pelagic thresher shark, which is targeted for its exceptionally long fins.

We analysed the trade in the species Alopias Pelagicus, which is the most endangered of these species. We again analysed the CITES trade data in kg and then did a cross-check on number of specimens reported. These sharks were also listed in 2017, so we analyse trade data from 2017-2022.

The main trade is between Ecuador and Peru and the trade is of great concern to the NGOs monitoring it due to its lack of sustainability.

At least in this instance the top importer and exporter rankings match between what is reported by exporters vs. by importers, even though there is a huge discrepancy in the quantities reported as we saw with the silky shark as well. The ranking for the top trade terms match with both sides agreeing that the trade is basically all conducted in fins:

Further, there are almost no trade records for trade recorded by ‘number of specimen’, which gives a more consistent picture than in the case of the silky shark. This shows that it would certainly be possible to get a better approximation of reality from CITES trade data if the efforts are made to:

- Keep the units and trade terms reported consistent for a species (or a range of similar species)

- Make sure that all importers submit trade data and that exports can be reconciled with imports

To achieve this requires rectifying the shortcomings of the present system. The first point is simply about demanding consistency from the signatory countries. CITES and conservation agencies have been encouraging signatory countries to do this for decades without any real progress. But rolling out electronic permits could ‘force’ consistency, by dictating what units to use for what species. Permits would only be generated if they were correctly filled in.

All signatories need to move to electronic permits and link those permits to customs data. That way permits can be matched to shipments and reconciliation between importers and exporters will be possible, but only if import reporting is made mandatory (which it isn’t for Appendix II listed species). It is critical that CITES mandates import permits for all trade in listed species.

All of these discrepancies beg the question, how can there be any proof that these species is being managed and protected; or that this trade is sustainable? The most basic reconciliations are not possible. The idea that ‘someone’ is properly monitoring populations to make these assessments to update Non-Detriment Findings is just as fanciful as hoping that we can learn anything useful from looking at CITES trade data.

What does this mean for the new listing of sharks?

While the decision taken at CITES CoP19 does mean that more sharks have a greater protection on paper, the data shown in this high-level summary shows this means little because the most basic reconciliations cannot be achieved.

So, it is extremely disappointing to see statements such as those made by WCS in Forbes: “Now no trade will be possible unless it is sustainable – giving these species a chance to recover, and the strength of CITES listings will drive stronger protections for sharks and rays around the world,” said Luke Warwick, Director of Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Shark and Ray Conservation. “The proposals adopted today for requiem and hammerhead sharks, championed by the Government of Panama, will forever change how the world’s ocean predators are managed and protected.”

This is blatantly not the case because of how data is collected. But, in such statements WCS is not alone. The question is why statements such as these happen time and time again, with listing changes at CITES. It screams of perception management for donors and the public.

While the public knows that governments, industry and business have perfected the art of perception management, they hold the conservation industry to different standards.

When incorrect statements such as “Now no trade will be possible unless it is sustainable” are made and then bounce around the mainstream media echo chamber, all it does is give the fishing industry the opportunity to say that is ‘complying with all CITES regulations’ in their sustainability reports. Given that CITES trade data is such poor quality, this effectively allows business to make meaningless statements and maintain business-as-usual. Why would the corporate conservation sector enable this?

So should we be excited that a record number of species to be regulated by CITES after CoP19? The proof is in the trade data which confirms that while CITES trade analytics is so poor these decisions are just protections on paper.

Additional Considerations For Protection Of Marine Species

While the CITES poor quality trade data must be fixed, it is not the only issue that must be held accountable to change.

An article published in early November, Hot Spots Of Unseen Fishing Vessels, discussed the lack of effective monitoring which has allowed illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing to operate on a large, systemic scale. The paper outlines vessel tracking data from the automatic identification system (AIS) and how it is a powerful tool for combating IUU. The researchers go on to show that AIS transponders are routinely disabled and present a global dataset of AIS disabling in commercial fisheries, which obscures vessel activity.

Fishing vessels from China, Taipei, Spain and the USA were found to be the top 4 countries with time lost to suspected AIS disabling events.

But what is the consequence of this? Do these vessels have their catch confiscated on their return to port? Do they have their license to fish suspended for a length of time, increasing with each suspected AIS disabling event? Do the companies who own the vessels receive a fine for not maintaining key equipment? And, if not, why not? Only if this is the case would commercial vessels ensure that their AIS system is well maintained and always on.

One reason for not dealing with the fishing industry is that lax regulations too often allow fishing vessels to hide their ultimate ownership behind complex corporate ownership structures and shell companies, rendering true accountability for illegal or harmful activities difficult to prosecute. A new web tool, Triton, launched by USA based C4ADS visually displays the corporate structures behind fishing vessels. In the first instance Triton data focuses on the industrial fishing fleets of five key flag states: China, Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, and Japan. Given that the US industry is not a focus in the first instance, does this mean that US corporate structures behind fishing vessels are already transparent?

One final interesting point to note is that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – an intergovernmental body tasked to combat money laundering – does not include the fishing industry in its mandate when looking at money laundering associated with environmental crime. Curiously, the fishing industry seems to have got off the hook!

An email was sent to C4ADS asking why the USA corporate structures behind fishing vessels were not being published and if they are already transparent? An email was also sent to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to ask why the fishing industry isn’t included in their monitoring. At the time of writing this article neither organisation had responded to these questions.