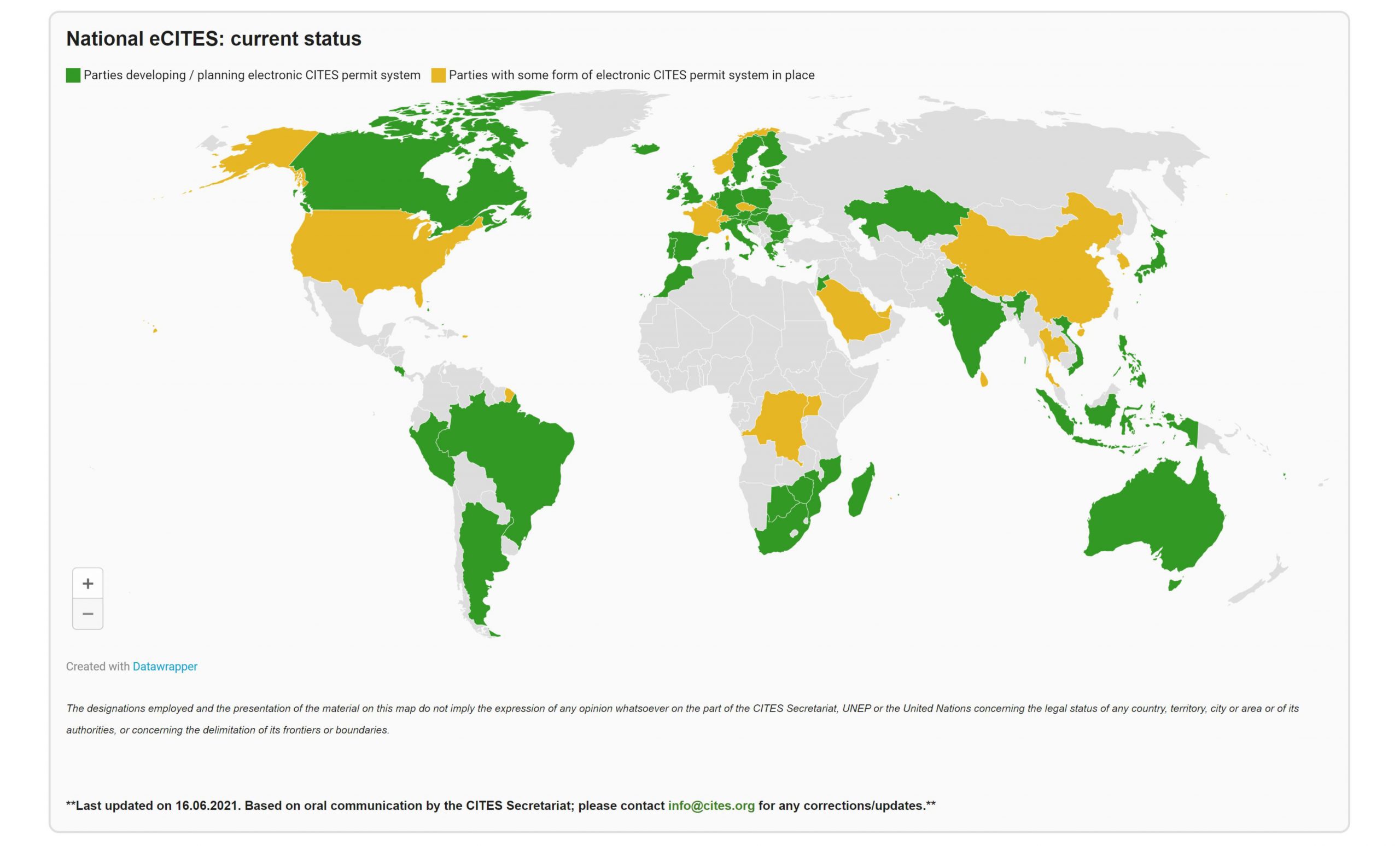

A map went up on the CITES website recently; it shows which of the 183 CITES signatory parties have some form of electronic permitting already in place (14 signatories, colour amber) and how many parties are developing/planning an electronic CITES permit system (30 parties, colour green). Maybe the first thing to mention is, why would CITES invert the normal project management ‘traffic light colour’ convention, making amber ‘implemented’ and green ‘in progress’. Cynically, I would say that at a glance this makes the project’s progress look better than it truly is.

The map shows there has been a small increase in the number of countries who have upgraded their permit system, compared to when we started lobbying CITES to move from the 1970s paper-based permits. When we began this project, in September 2018, only 2 countries had implemented electronic permits. Given the current status, I think it is justified to call this the Map of Shame.

CITES signatory governments, together with the businesses who make huge profits from this trade, valued at US$360 billion annually, need to do much better. Business in particular need to put their hands in their very deep and full pockets and pull out the less than US$30 million needed to complete the global rollout of the CITES electronic permits. If they can’t do this, they must expect a growing push for No Transparency, No Trade.

So, are there any positives about having this map? Since moving to electronic CITES permits was first discussed in 2002, now, there is one central point to review who has, who is considering and who isn’t yet thinking about rolling out electronic permits. I can certainly vouch for how difficult it has been to seek out clear information on the status of this project over the last few years. We have a small step on the road to transparency, showing the current state of play, from CITES perspective and a central point to monitor progress. This will mean governments can no longer lie or spin the progress on this project. The map is clear for everyone to see, and shows that only 7.6% of CITES signatory parties have implemented some form of electronic permits in the 20 years it has been discussed.

Nature Needs More has continued to lobby CITES for transparency on this issue, including through our invitation to participate in the electronic permits working group. In February 2021, the Secretariat sent out a Notification to Parties asking them to submit their status and plans in relation to adopting electronic permitting. The map was published from the responses received.

While the map is up, it must be said that there is currently no clear definition of what constitutes a parties system being labelled ‘Amber’. From Nature Needs More’s perspective, to receive this ‘Amber’ status this should mean:

- For governance and independent monitoring, the CITES signatory party’s system has interoperability with the central monitoring system hosted by UNCTAD, and,

- Where a party chooses to built their own, customised system, and did not use the UNCTAD eCITES Base Solution, the party has agreed to pay all ongoing interoperability cost and the cost to ensure that their system is kept up to date at all times, and,

- Electronic permit exchange between countries is enabled. Currently, the degree of interoperability varies widely, and electronic permit exchange has only been implemented in a handful of cases.

So why should the conservationists, who accept CITES (and the legal trade in endangered species), be concerned about the glacial speed in moving CITES from the 1970s paper-based permit system to electronic permits?

- Firstly, as Nature Needs More outlined in the June 2020 Debunking Sustainable Use Report, the sustainable use model cannot currently be validated and, to-date, in the nearly 50 years CITES has been in operation, the sustainable use model has not been proven.

- In addition, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and specifically SDGs 14 and 15, cannot be realised.

- Likewise, Target 5 of the draft CBD post-2020 global biodiversity framework, which states that “the harvesting, trade and use of wild species is sustainable, legal, and safe for human health” will not be successful without modernising CITES.

The biodiversity strategy being discussed for the next decade is unattainable without the first step of making international supply chains radically transparent.

You can see from the map, that key regions from a biodiversity and trade perspective, have low adoption rates for CITES electronic permits, and appear to have no plans to move from the CITES paper-based permit system. The regions of concern include, Continental Africa, Russia, Central Asia and the Middle East, Oceania and Latin America.

Looking at the regions highlighted in red, there are specific concerns for each when it comes to the loss of terrestrial, marine and freshwater species. In many areas there is social and political instability, which means wildlife comes very low in the list of priorities when a government has a limited budget or political will.

To understand the implication of the lack of transparency in the trade of endangered species in these regions, let’s just talk about one: Central Asia. Only Kazakhstan is currently planning or developing an electronic permit system.

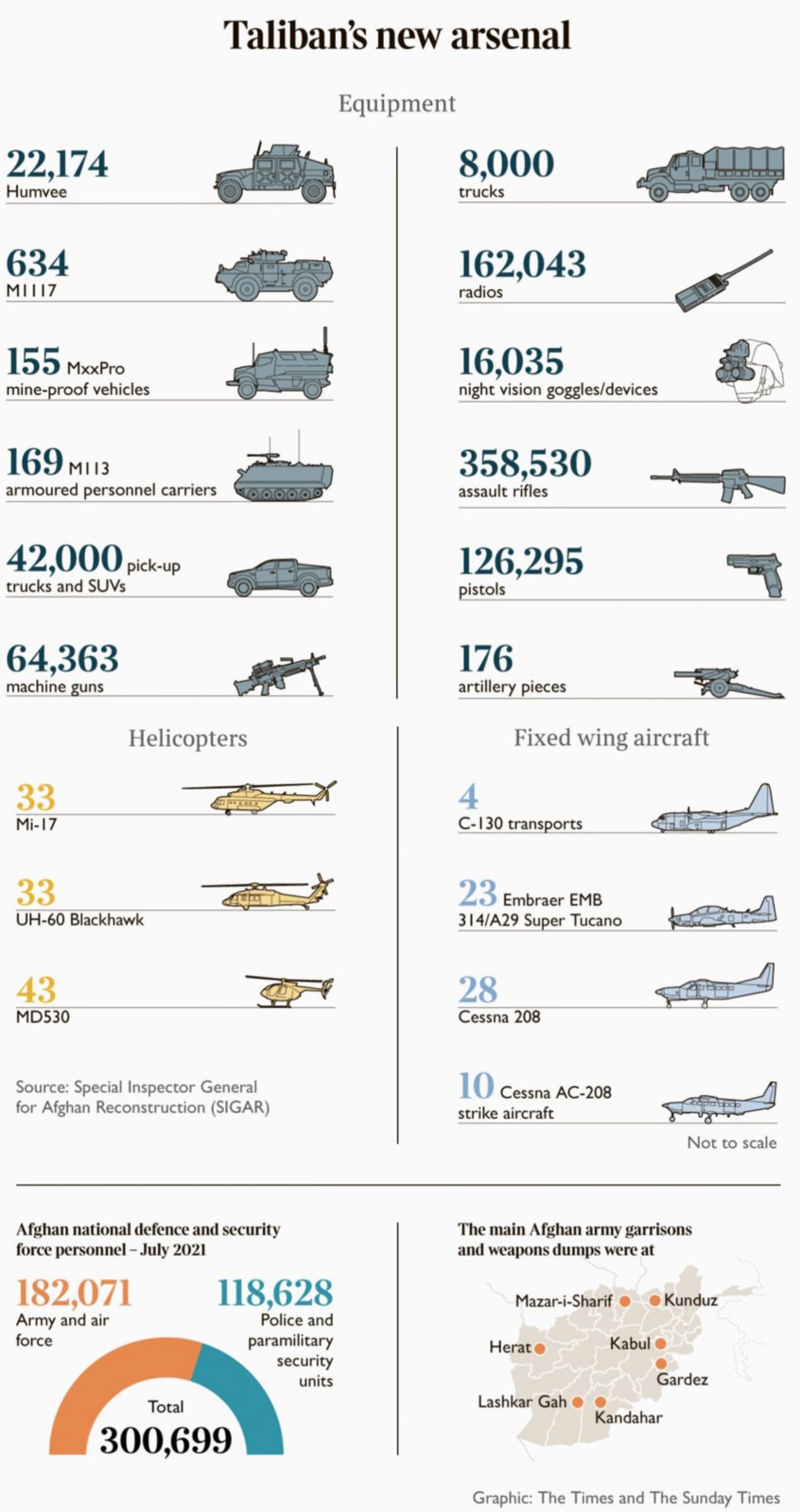

This region is high on people’s radar, specifically because of Afghanistan. The news coverage of the allied forces exit from Afghanistan showed the arsenal of military equipment and arms that were left for the Afghan army; all of these are now in the hands of the Taliban. Some news outlets stated that the Taliban now has access to $85 billion worth of American military equipment, vehicles, airplanes, helicopters, small arms and light weapons. While there is dispute about the actual true figures, TV news segments did show the volume of equipment left behind was significant.

At the same time Afghanistan is a key country for the drug trade and a trade route for heroin and people smuggling. Transnational crime supply chains are already in place and, as we know, these can be easily ‘re-used’ for the trafficking of endangered species.

So now we have a much more well armed, unstable region of the world, that is already a trade root, and wants access to more money to deal with a bankrupt economy; not a great combination for wildlife. It would have cost next to nothing, compared to the value of the weapons left behind, to help Afghanistan implement an electronic permit system. Same for the other countries in Central Asia. While it may no longer be possible to implement a CITES electronic permit system in Afghanistan in the short term, the current situation in the country means that it is critical to implement a modern CITES electronic permit system in all the countries bordering Afghanistan, namely: Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan and Iran.

Governments continue to prioritise war and economic development whilst ignoring the most basic protections for biodiversity. This needs to be change urgently.

In addition, we are nearly 2 years into a global pandemic which is zoonotic in origin. The pandemic has killed millions of people worldwide, because the line between us and exotic animals has long been breached for trade. The scale of the legal, unchecked over-exploitation of wildlife, which has been going on for decades, means we have walked blindly into this minefield, all for the want of a minimal investment in independent regulation and monitoring.

It would be so easy to turn the map of shame into a beacon of hope with a funding commitment to help all remaining countries to move to electronic permits and electronic permit exchange.

Such funds could come from traditional funding sources, such as the World Bank Groups Global Wildlife Program or the Global Environment Facility (GEF). But they could also come from the less traditional, for instance the companies involved in President Macron’s, Fashion Pact, the Bezos Earth Fund or the companies who use CITES listed species and are signatories of Business for Nature.

A recent Nature Needs More blog Quite Ridiculous: Why Endangered Species Miss Out On QR Code, showed just how quickly governments have rolled out QR-Code COVID certificates to decouple the vaccinated from the unvaccinated. It is time for any stakeholder in the trade in endangered species, who wants this trade to remain, to aid the implementation of an electronic CITES permit system. They have had 20 years to discuss it, now we need real action, and not just talk, to rollout a system that can decouple the illegal and legal trade in endangered species.

If they make this commitment, we can take this map of shame and turn it into a beacon of hope. This is such a real and pragmatic way to help tackle biodiversity loss and the current extinction crisis that we can’t accept any more excuses, and any more delays, in this necessary first step to modernise CITES.