Are 2,000 captive-bred, farmed rhinos of any value from either a commercial or conservation perspective?

John Hume, the owner of the world’s largest private rhino herd, is auctioning off his rhino farm, the starting bid being US$10 million. The question is, what are Hume’s rhinos really worth?

In recent weeks there have been quite a few emotional appeals from John Hume and his supporters to ‘see the value’ in what is being offered. I get that many people believe that this is John Hume’s life’s work, but the US$150 million the one-time billionaire reportedly spent on this enterprise is, in business terms, the project’s sunk cost. It is a business risk he chose to take, as he farmed rhinos with a view to selling the horn.

When he started, over a decade ago, the international sale of rhino horn was already banned and the domestic trade was banned in South Africa for a number of years until John Hume and Johan Kruger launched legal action, saying it is their constitutional right to sell rhino horn. Izak du Toit, the lawyer who represented the rhino owners to overturn the domestic trade ban, and who appears to be Hume’s legal representative in the current auction, said at the time, [If the domestic trade ban was overturned] “We would sell [rhino horn] to the poachers to prevent them from killing rhinos,”.

With all the effort to overturn rhino horn trade sanctions, both domestically and international, there was always an inherent risk in Hume’s strategy that the trade ban would remain, and he accepted this risk as legalising the trade in rhino horn was the only way to recuperate his investment. Hume has said that his 10-tonne of stockpile of rhino horns is negotiable as part of the current auction, adding that it is worth more than US$500 million on the black market. A curious message to give out.

The fact that there is still a ban on the international trade of rhino horn doesn’t change the lack of trying by Hume and other South African private rhino owners. Over the years they put forward models for a ‘regulated’, international legal trade in rhino horn. The business plans have loopholes big enough for a Mack truck to drive through and, in all this time, they have never invested in a consumer analysis. The pro-trade supporters have previously stated that, “What they [rhino horns] are used for is hardly relevant. The fact is that people are willing to pay.”. Even now, after more than a decade of pushing to legalise the international trade, the response to the FAQ page question, “Does anyone know what the demand for rhino horn is?” is, “There is no reliable data on the size of the market. The best way to determine the characteristics of a market is to engage in legal trade.”. Mmm, quite a risky approach if your goal is to save rhinos from poaching.

At least now they acknowledge that an international trade won’t stop rhino poaching, the response to the FAQ page question, “Doesn’t the market value ‘wild’ horn more than harvested?” is, “Possibly, yes. If there is a preference for ‘wild’ or whole horn, this will be reflected in the price buyers are willing to pay.”. A far cry from their earlier, evidence free, assertions that the supply from the privately owned rhinos in South Africa could satisfy demand in Viet Nam and China and that consumers would be willing to substitute farmed horn for horn from wild rhinos.

Legalising the trade in ivory for two massive one-off sales did not stop elephant poaching, it made it worse. There is every reason to believe the same would happen with rhino horn – as soon as you can legalise advertise you can create new demand; something else they have never been willing to factor into their pro-trade push. Further, those who can afford genuine rhino horn will pay for a ‘wild’ product. Consumers have been known to ask for the tail/ears of the rhino to be presented with the horn to show it was killed in the process and the horn didn’t come from a stockpile.

This rhino sale mess is a perfect demonstration of the misguided obsession with the commercialisation of wild species. John Hume and the other private rhino owners managed to overturn the ban on domestic trade in South Africa, but that did not create a market for a product nobody needs. Hume’s rhino horn auction in 2017 was a flop, as was his later attempt to launch a cryptocurrency backed by rhino horn.

John Hume’s 2,000 rhinos and his reported 10 tonne stockpile of rhino horn have zero commercial value as long as the international trade remains closed. Reinstating the South African domestic trade in rhino horn was seen a precursor to overturning the international trade ban, providing hope for the pro-trade rhino owners. The result was they were happy to devalue rhino horn from a poaching perspective but they have never wanted to devalue horn from a consumer perspective, as they didn’t want to undermine the potential for future profits.

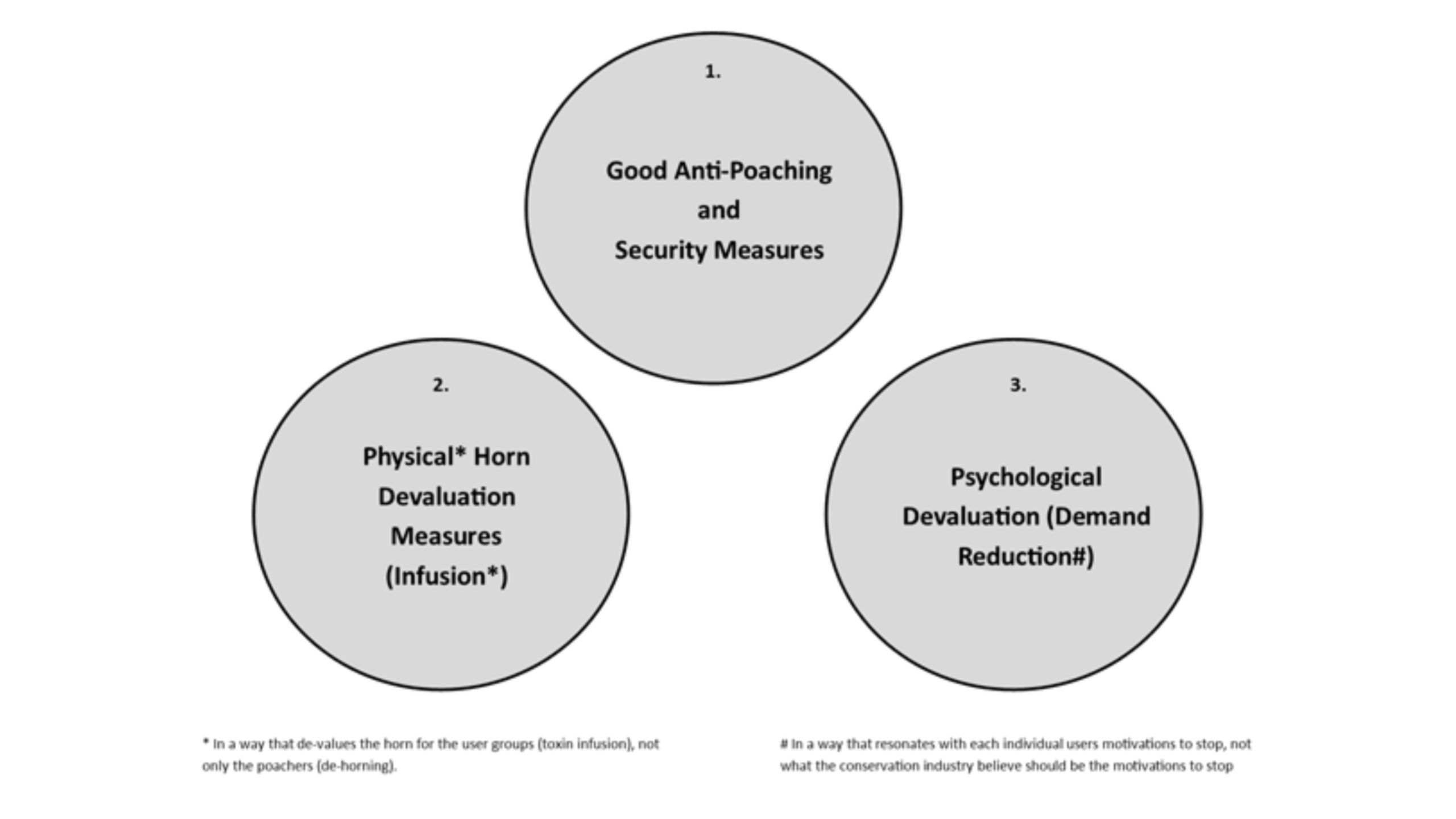

As I wrote in 2014, a successful strategy to stop rhino poaching needs to be three-pronged. It needs to invest in security, physical devaluation in the eyes of the genuine consumer groups and psychological devaluation in the eyes of the genuine consumer groups. The rhino owners in South Africa stopped a viable and proven rhino horn injection project as they did not want to physically devalue the horns; the Vietnamese rhino horn users I interviewed in 2013 and 2014 were certainly worried about rhino horn infusion.

Demand reduction campaigns (psychological devaluation) had no chance because of the mixed messages being sent out. Only a handful of the demand reduction campaigns targeted the actual consumers, most campaigns focused on education and awareness raising instead, while calling themselves demand reduction; this provided great ammunition for the pro-trade lobby groups.

If John Hume’s rhinos have no commercial value, what are they worth from a conservation perspective? After all, Hume owns nearly 12% of the remaining Southern white rhinos in the world.

For Hume’s rhinos to be valuable from a conservation perspective, there would need to be evidence that they could be successfully rewilded.

Hume offered to give away 100 rhinos a year for rewilding if the takers would cover transportation costs. Attempts have been made to rewild rhinos, including in Chad and Kenya, both unsuccessful. The rhinos relocated to Botswana were decimated by poachers, showing that without the investment in security any current attempt to move his rhinos is doomed to fail. As yet, there is simply no evidence of value from a conservation perspective. In the same way as conservation groups have challenged the captive breeding of lions in South Africa, when there is no evidence that they can be successfully rewilded, is the lack of rhino rewilding success simply another CON in CONservation?

Maybe the only current value of John Hume’s failed experiment would be if it triggered a review of the model for private ownership of wildlife in South Africa, and beyond.

The South African model of private ownership has led to an obsession with the commercialisation of wild species by some owners, the clearest example being the captive breeding of lions for the lion bone trade and canned hunting.

The scale of wildlife commercialisation in South Africa certainly hasn’t prevented biodiversity loss in the country. A 2020 report by Swiss Re, the world’s second-largest re-insurer, confirmed that of the G20 countries, South Africa is ranked in first place for failing and fragile ecosystems. Encouraging private ownership and making money from selling wildlife has not stopped South Africa from being ranked in first place for failing and fragile ecosystems.

There is going to be a lot of hand-wringing over the coming days, what happens if and when Hume’s auction fails. It didn’t need to come to this. Allowing individuals to farm wildlife for which there is no legal market was always a stupid idea.

Rhinos shouldn’t be private property and we need to stop believing that (further) commercialising nature is going to reverse biodiversity loss. The landmark May 2019 IPBES report into the global extinction crisis confirmed the commercialisation strategy hasn’t worked, as direct exploitation for trade is the most important driver of decline and extinction risk for marine species and the second most important driver for terrestrial and freshwater species. The desire to supply is driving biodiversity loss.

It is time for some new thinking.