In recent years, as I have been monitoring the rhino horn trade/no-trade debate, it has become apparent that conservation groups, large and small, have very little ability to deal with government, donors, agencies, organisations or individuals who have a (overt or, particularly, covert) pro-trade agenda. This inability to fight back is not just about rhino horn, it is also why we find ourselves in a similar position on climate change, mining and many more issues.

Reflection and Questioning

Over the last year, we are seeing more articles of the type:

- Why conservation is failing

- Has big conservation gone astray?

- How big donors and corporations shape conservation

- And even the seemingly unchallengeable has been challenged: The BBC’s Planet Earth II did not help the natural world

On one hand conservation agencies publish reports that consistently drive home the crisis, hoping to mobilise the public. Yet internally they maintain their ‘business as usual’ behaviours, mainly chasing donations for projects that haven’t delivered and aren’t going to in the timeframe needed. All this despite there being only one more CITES meeting, in 2019, before the 2020 deadline set in the 2016 Living Planet Report.

There is a mountain of evidence to say conservation has been caught napping and it has been manipulated and co-opted by the neoliberal and pro-trade agenda.

So, why is conservation failing?

It is long overdue to look at why this has happened and how to rectify it. In a March 2015 blog: Conservation vs. Wildlife Traffickers. Who do you think will win the war in wildlife crime?! I wrote about how few conservation people I had met who can think strategically, they were all tactical. Two years on and a lot more meetings with the sector, this hasn’t changed. I could count on one hand the strategic thinkers I have met and this is a real problem.

As I write in the blog “As donors we have to take some blame for this. We have become neurotic about the fear of being ripped off by poorly managed NGO’s that we question how every dollar is spent. As donors, we have the right to ask NGO’s to provide transparency, efficiency and effectiveness in spending the funds given. Because donations are often given with instructions that they must be spend on a specific project this appears to have resulted in the underfunding of professional development in the not-for-profit sector for quite some time.”

Yes, people working in conservation are supported to do research, present and go to conferences and write academic papers. This has honed their specialisation and what I’ve seen, from nearly 20 years of executive coaching, is that specialists rarely make good problem solvers of problems that matter. Additional professional development is required so the conservation sector can respond in a scientific, political and commercial way to the current wildlife poaching and trade issues.

The over-valuation of the specialist expert

Being a specialist expert is only useful until it is not! There comes a time when you need to take a step back from the depth of knowledge and use breadth of perspective. It is not unusual to meet managers, even executives, in any sector who have not transitioned from a technical to a strategic mindset. This inability to develop a strategic intuition maintains silos and reduces leadership effectiveness. So why is specialist thinking so prevalent; and why has it seemingly become overvalued?

In recent history our universities and corporations have created the culture of the expert. To use an analogy from Vikram Mansharamani – Lecturer at Yale University – if we think in terms of a forest, corporations around the world have come to value expertise and, in so doing, have created a collection of individuals studying bark. There are many who have deeply studied its nooks, grooves, colouration, and texture. Few have developed the understanding that the bark is merely the outermost layer of a tree. Fewer still understand the tree is embedded in a forest.

At the same time our global society is getting more complex and uncertain. Research undertaken over recent years, by individuals including Professor Phillip Tetlock of the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School, is providing robust data which suggests generalists are better at navigating uncertainty, are more risk tolerant and demonstrate greater levels of adaptability than specialists.

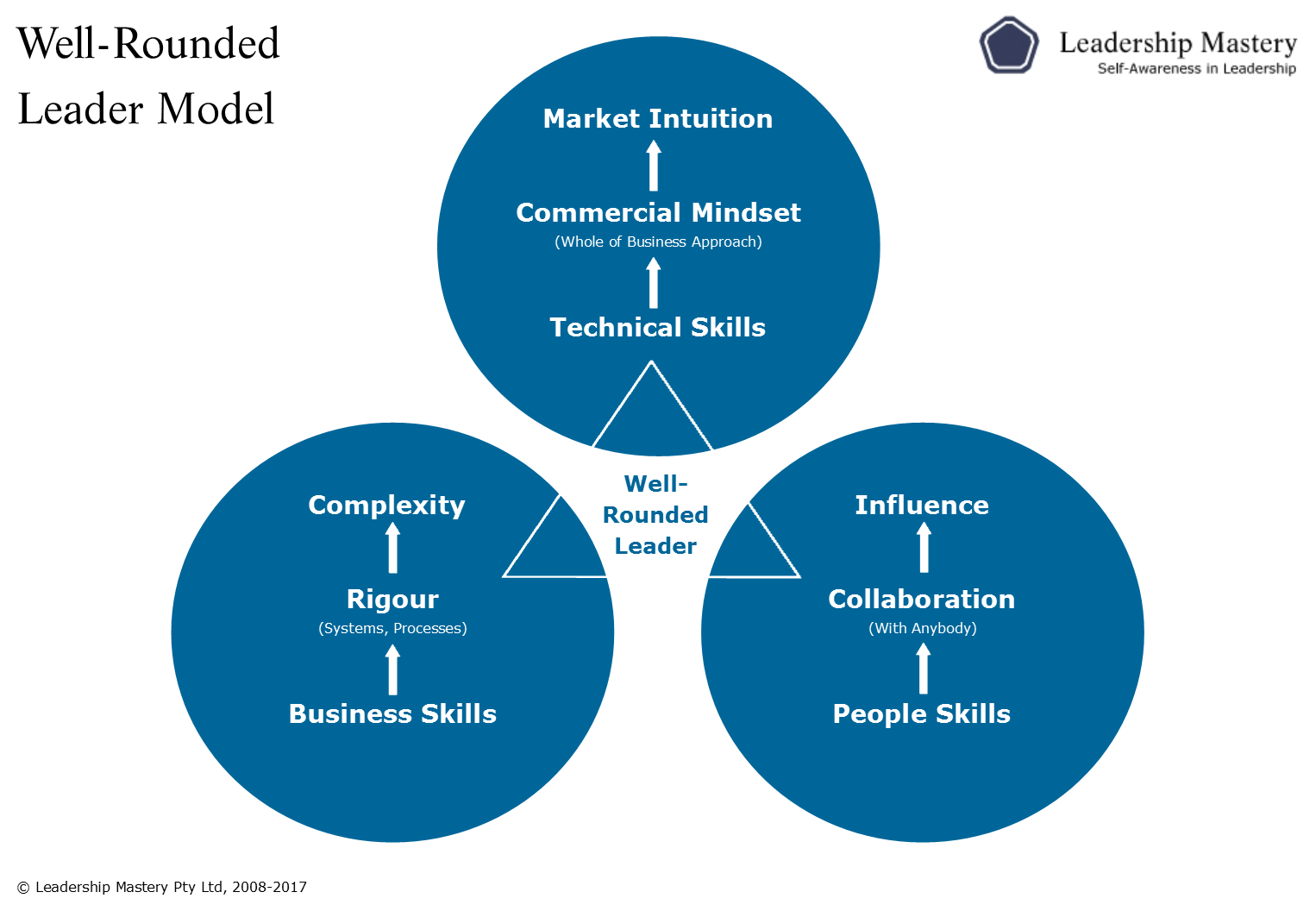

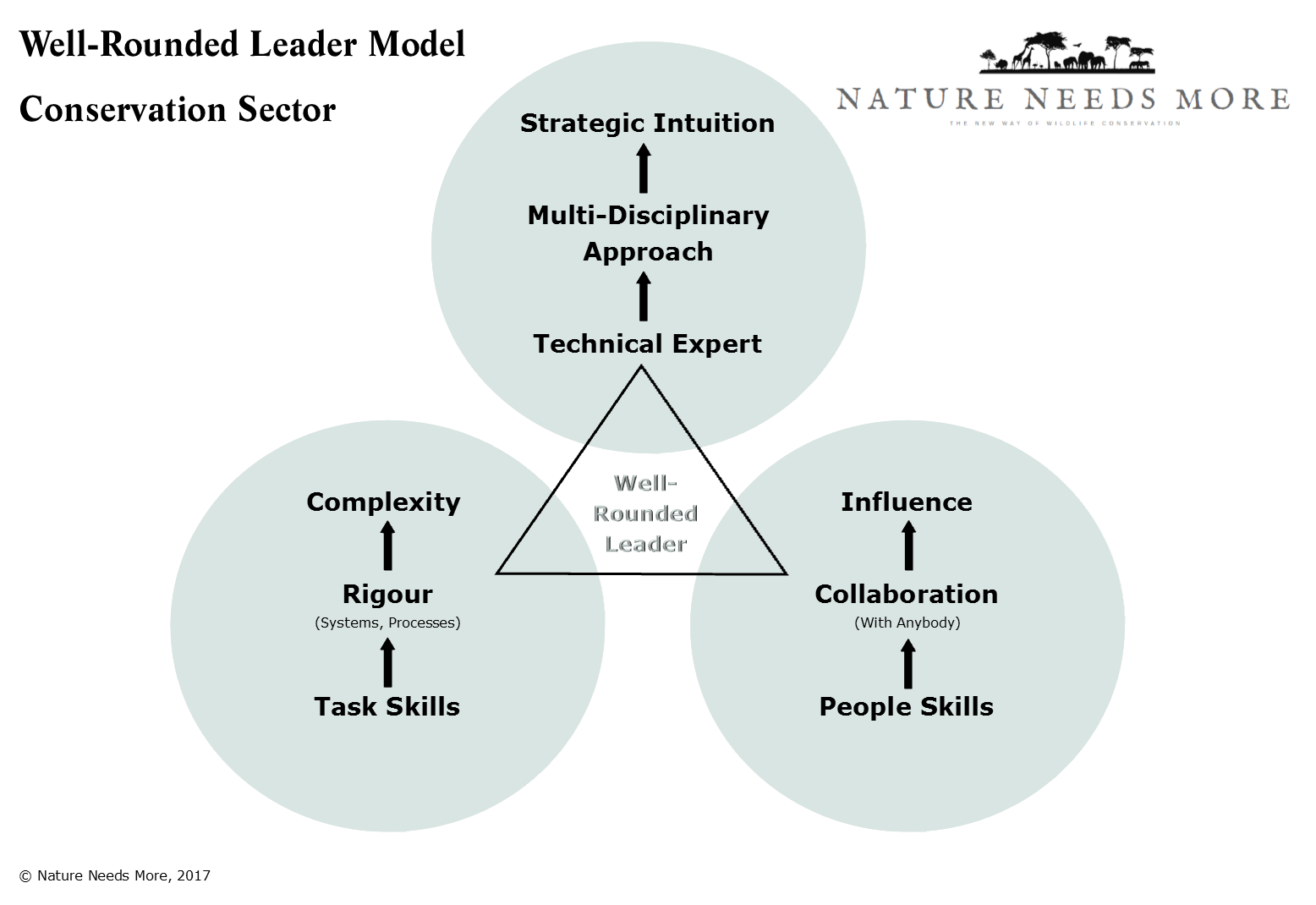

Companies have, to a degree, realised this. Conservation has, in the main, not. As a result, many companies have invested in pulling their technical specialists up out of the detail. In my executive coaching work I developed, and have been using, the Well-Rounded Leader Model for many years. I decided to adapt the model to highlight the professional development needs required in the conservation sector to keep their skills relevant to the emerging problems.

Commercial Model #

Conservation Model #

Development in all 3 areas is required to become an effective leader with a strategic intuition about where to put your focus.

Our technical expertise usually forms the basis of our career. Most of us start out becoming experts in a particular field. In the commercial world, as people strive to advance in the management hierarchy, they need to develop breadth, not depth, for role effectiveness. This means going from a narrow focus on their area to a whole of business approach. The first step in doing this is to stop honing what they are already good at (technical expertise) and start working on their area of weakness.

By developing a commercial mindset, managers lay the foundation for becoming intuitive about where their industry and the market are going. They learn to present ideas in the form of business cases and start to take the needs of the whole business or value chain into account when thinking about decisions or changes that need to be made. They make decisions for the good of the business as a whole vs. not just the good of an individual’s area.

Making these transitions requires tenacity and maturity; this is the point when people deal with their ego issues and grow up professionally. We see 3 transitions where people often get stuck:

- Oscillating between level 1 and 3 and bypassing the middle level 2, e.g. from people skills to influencing, bypassing collaboration with everyone. It results in a manager being only able to influence the people who they would naturally influence. The result is a hit and miss approach that reduces overall leadership/communication effectiveness.

- The perfectionist trap. This is the classic overvaluation of the specialist, in focusing on technical expertise and rigour. People stuck at this point have often moved beyond rigour/technical too rigid/nit-picky.

- The hero trap; these are people who are seen as technical experts who are also nimble problem solvers. There are 3 key issues with this group:

- Because they are stuck in technical (tactical/operations) they are very good at solving symptoms, but very rarely get to the root cause of the issue

- They love to be heros, in which case they often need to maintain the problem (you can only be a hero if there is a victim)

- They can get hooked on power and won’t develop people as they know that their level of expert knowledge has given them power.

In summary, technical experts aren’t good lateral thinkers, they tend to be risk adverse and they believe their model of the world is right. They struggle to understand other people’s point of view. Similarly, they tend to completely miss the importance of political agendas and power plays.

How prevalent is the Strategist?

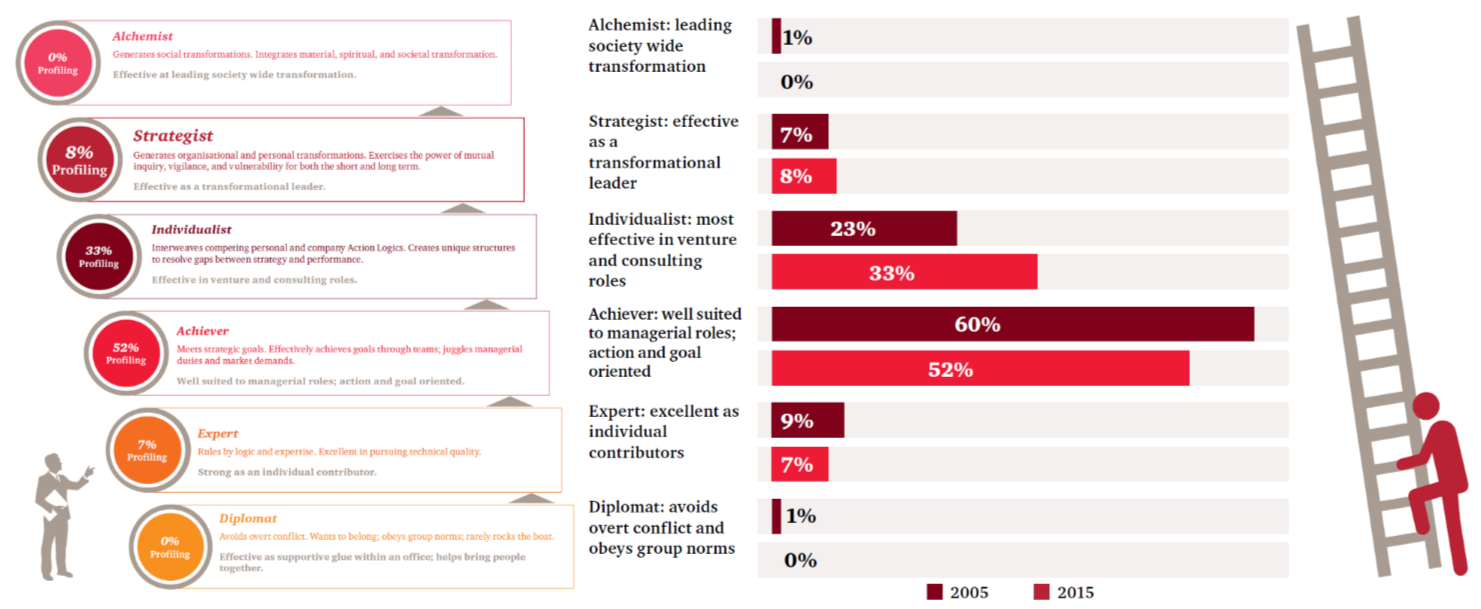

One of the tools I use in my day job to help managers and executives understand the behavioural stage they have developed to is the Leadership Development Framework developed by Harthill Consulting. A collaboration between Harthill Consulting and PwC profiled over 6,000 leaders across industries and sectors and sought to identify those who profiled as ‘Strategists’, defined as leaders who have the appropriate capabilities to prepare them to successfully lead business change. The data demonstrated less than 10% of leaders have the appropriate Strategist capabilities to successfully lead through complexity. In the general population, this would be much lower than 10%, in the consulting world 29% profiled as Strategist. So, the question is, if you profiled the conservation sector, what percentage of people do you think would profile as Strategist? The vast majority certainly appear to be Experts and as the diagram below highlights they are strong as an individual contributor; which isn’t enough to solve complex problems.

Why are Strategists important?

This is nicely covered in the PwC publication, where they highlight that problems can be divided in to 3 kinds: Tame, Critical and Wicked. Many of the problems that leaders face that require transformational change in their organisations can be classified as ‘wicked problems’. I certainly believe that the problems facing the conservation sector can be classified as ‘wicked’. We need leaders with strategic intuition, who recognise (covert) agendas and deal with them surgically. These same people need to be able to influence stakeholders to tackle priorities, no matter how difficult, not symptoms.

What might be a starting point? Genuine, multi-disciplinary collaboration.

I will say that, without exception, everyone I have met in the conservation world talks about the need for collaboration. It is often met with mumbled laughter from the group and someone pointing out the unicorn that just walked past the window. So why, when it has been talked about for quite some time now, is it not been done in any useful way?

Firstly, until a technical expert understands and accepts (at least intellectually) that a commercial mindset or multi-disciplinary approach is required to solve the problem, they just pay lip-service to collaboration without really committing to the necessary change in their behaviour. In addition, simply put, collaboration is hard, creates overheads, requires a time investment, reflection, self-awareness and an ability to overcome your fears and ego.

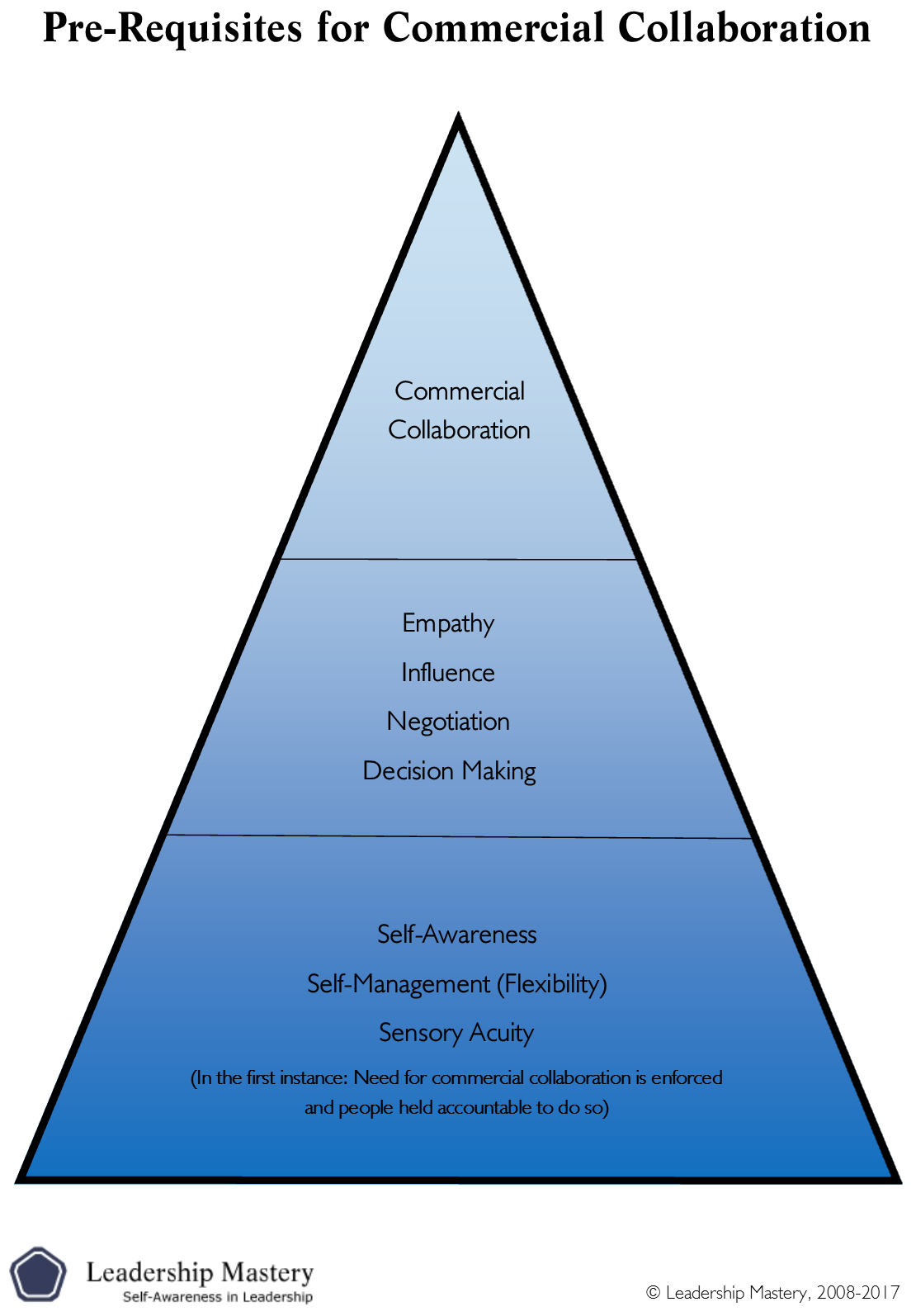

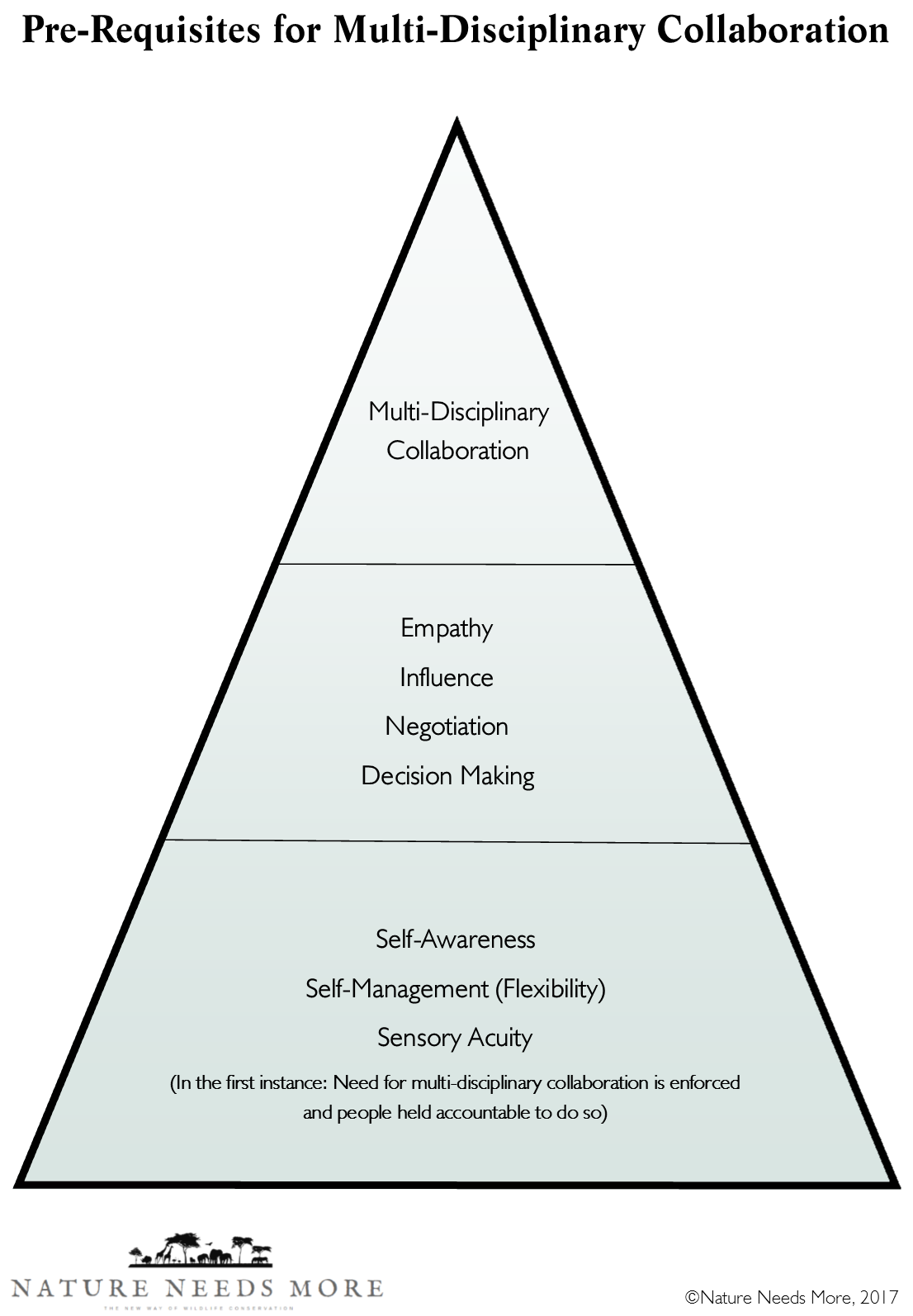

It happens in the commercial world primarily when people are forced to collaborate, held accountable to do so and given the skills to make the necessary behaviour change. Again, I show below the model we use with our clients and how I would modify it for the conservation sector.

Commercial Model #

Conservation Model #

It must be acknowledged that it is company executives and board members and markets (externally) that force the need for collaboration. In the multi-disciplinary conservation space, there is no such pressure. Most likely it would come from large donors, but are we sure that they all want to see us collaborate?

Is perhaps the conservation sector’s lack of strategic intuition a benefit to large donors, government and the private sector?

Well, 40 years of neutering the climate change movement would indicate the benefit to neoliberal governments and their corporate puppet masters. How many people remember that Jimmy Carter installed 32 solar panels on the White House roof when he was president in the late 1970s? When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, one of his first actions as president was to have the panels removed. Hard to imagine how much better placed the world would be in dealing with climate change if the climate change deniers hadn’t been so powerful and so well-funded. The groups who want to trade in animal parts have had 4 decades of role models to learn from.

After 4 years of observing large conservation, given the lack of strategic intuition I have seen in the sector, maybe it is not a surprise that I would describe it as stable, but not so useful.

I see a small number of disillusioned people who would love to see these types of professional development needs addressed. What is also apparent is that they don’t know how to sufficiently ‘disrupt’ the sector fast enough from within. Frankly, I hope they stick around for more than the next 5-10 years, before exiting the sector if they can’t see any significant change. Unfortunately, the majority in the sector provide the level of ‘passive resistance’ to change that I go back to my earlier statement: ‘The system is stable, it is just not useful’.

In this situation, what can be done?

There are only three options:

- Invest in the professional development needs to evolve the skills of the conservation sector so more people develop the strategic intuition and skill needed; and enforce multi-disciplinary collaboration.

- Create an alternative system

- To paraphrase a Max Planck quote: “You wait for the old men to die”.

No matter what I think of Max Planck as a physicist, I can’t follow his particular thinking in this regard; the natural world is too precious to not at least try to make a difference.

I have met a handful of people working in large conservation who want the type of professional development I outline above to ensure the survival of the animals and environments they care about. I will continue to work with them, informally and in a pro-bono capacity. They are the beacons of hope for the sector.

In addition, this is also the reason that I am evolving Breaking The Brand to Nature Needs More. I accept that this will be a marathon rather than a sprint. Rather than Planck, I look to Machiavelli to understand the difficulty of the journey. I and the growing Nature Needs More team will continue to make our small contribution to the body of knowledge in the public domain.

As for the broader sector and the prevalent Expert mentality, if you persist in this frame you will continue to miss the point, the agendas, the politics and the power plays and will remain marginalised and ineffective in saving the natural world from the effects of unconstrained growth. Yes, you will be seen as an expert in your field, you will do and publish research, but you won’t be doing what you set out to do when you first heard the ‘calling’, you won’t be saving the planet. That’s tragic, because capitalism and the neoliberals won’t stop.

These are the views of the author: Dr. Lynn Johnson, Founder, Breaking the Brand and Nature Needs More