Perception management involves 3 techniques: deletions, distortions and generalisations. These techniques have been used consistently to divert attention away from the legal trade in endangered species and the failure of the system set up to regulate it. The aim has been to keep the public focused squarely on the problem of illegal trade and, in the main, this has worked.

When the failures suddenly enter public awareness, as in the case of the zoonotic and legal trade origin of Covid-19, the stakeholders usually scramble to acknowledge an ‘isolated incident’ or ‘single point of failure’ but refuse to talk about the long-standing systemic issues. We can no longer tolerate the perception management that the legal trade in endangered species is working.

For example, in a recent article, by Louise Boyle for the Independent UK, John Scanlon, who was CITES Secretary General between 2010 and 2018, said of CITES “[it] does not tackle consumption, wet markets, human health, animal health, invasive species”. Scanlon went on to say there were “gaps in CITES siloed approach” and that it was a “narrow focused regulator”. He “suggested bolstering CITES” and also said “I don’t think that can cut it in 2020″.

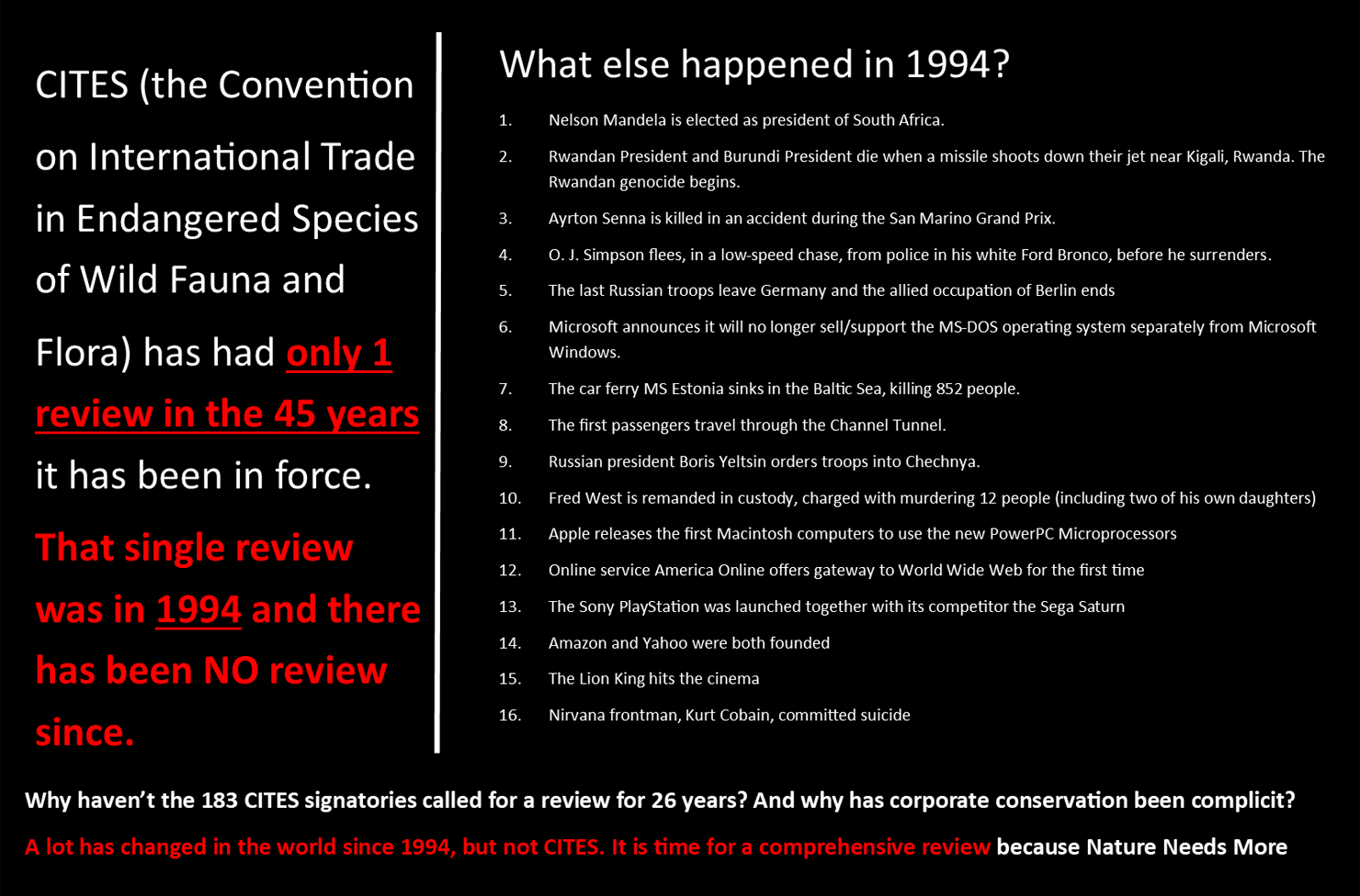

What Scanlon failed to mention was, since CITES came into force in 1975, the convention itself has had only one review and that was in 1994.

Any business or industry that doesn’t reflect on how it needs to evolve to adapt to the changing, external conditions would undoubtedly become ineffective (if in fact it managed to survive). Secretary-General after Secretary-General, including Scanlon, have not addressed the fact that the global context has changed while CITES has languished in a 1970s mindset and system.

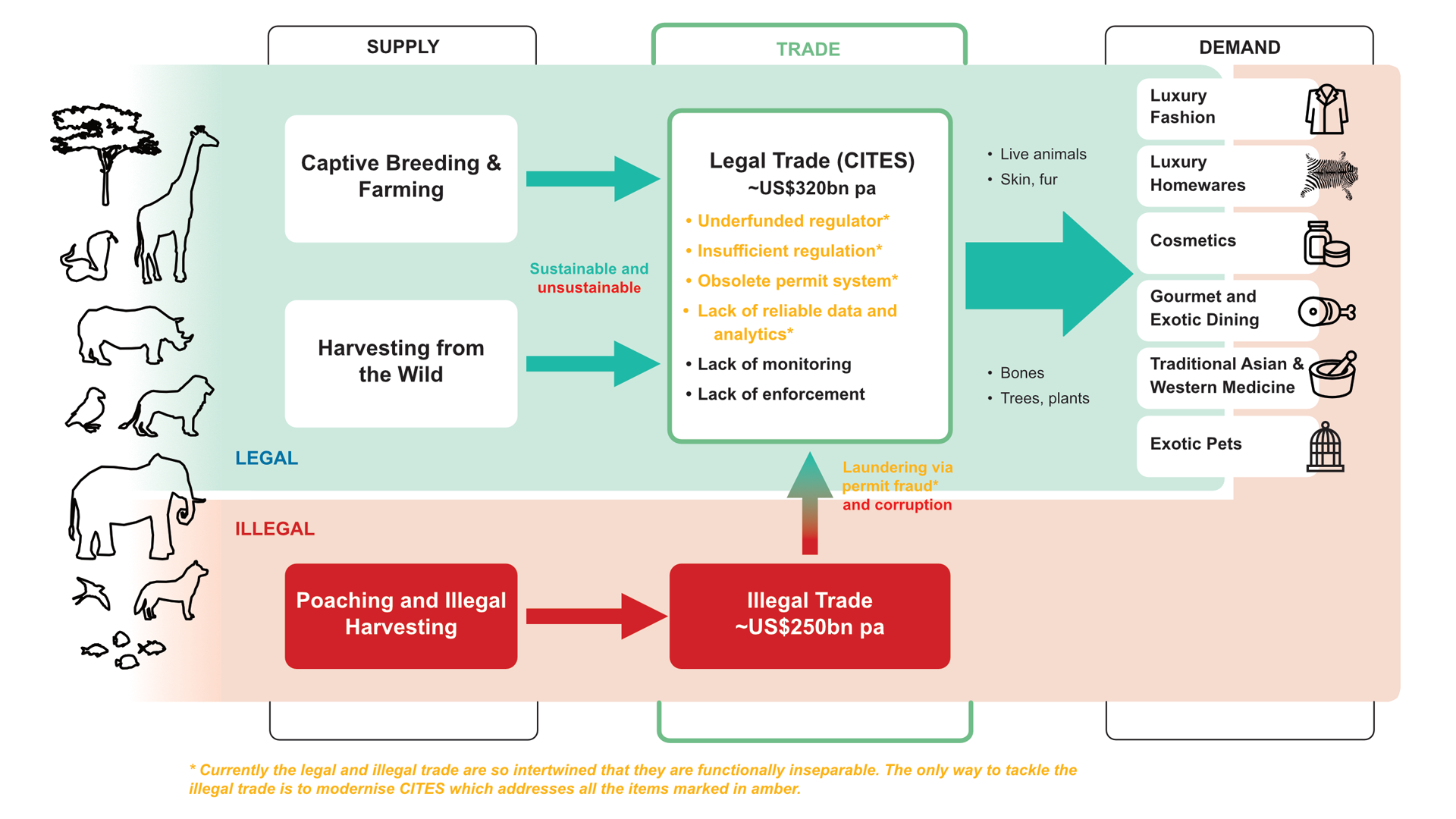

If the CITES convention had been reviewed every 5 years, to incorporate changing world conditions, including the rapid growth in consumption and increased biosecurity risks, then maybe it could ‘still cut it’. The number of species listed under CITES for trade restrictions today is nearly 36,000 (in 1981, at CITES CoP3, it was 700). It has been hidden in plain sight that the line between people and exotic animals has been continually breached to feed the demand for a US$320 billion annual legal trade in endangered species, through mass-scale captive breeding and increasing legal harvesting from the wild.

Oh, and don’t forget that the world has had a digital revolution since the 1970s, in which CITES has not taken part; how much longer does a multi-billion dollar legal trade need to rely on typed, paper permits? Of course CITES needs to be modernised, but the need to do so was equally evident when Scanlon was Secretary-General and he didn’t make any attempt to instigate modernisation.

Scanlon goes on to say “We now need to fully embed this in the international criminal justice framework,”; my response is no John, actually it needed to be embedded in the international criminal justice framework decades ago, the interesting question is why wasn’t it? I would have been interested in Louise Boyle asking that question. When Scanlon was Secretary General of CITES, between 2010 and 2018, the industrialised scale of poaching already started to receive more mainstream media attention. So why was CITES unable to have the trafficking of endangered species included under the UN Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime? It has long been accepted that wildlife and timber crime is the 4th-largest transnational crime in the world, so why has it not been officially recognised?

There are so many statements that need interrogating here. Scanlon remarks that the illegal trade in pangolins is at a record high, despite having the highest-level of protection under CITES. But he failed to mention that pangolins were only put on to Appendix I in 2016; it was the lack of monitoring of pangolin trade while it was still on Appendix II that was a huge part of the problem. The USA was a key destination for pangolin, check out the cowboy boots; the trade consisted of manufactured leather goods, skins, scales and meat.

In reviewing the legal pangolin trade data, researchers found all the usual CITES permit and database discrepancies as seen for other traded species. They also reported that pangolins were exported with CITES certificates labelled captive bred [C] from countries where there is no evidence of pangolin farming (the same as has been found for python skin). Most interesting is the fact that even after CITES put zero export quotas on pangolin in 2000, no one at CITES has apparently questioned or explained why permits for commercial trade in these specimens were still issued post 2000.

This is not the time to develop another, under-resourced convention. Remember that even though Scanlon established the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC) with funding of US$20 million, this is pocket change compared to the illicit trade valued at up to US$258 billion annually in the 2017 world Customs Organisation Illicit Trade Report.

Research over the years has confirmed, time-and-time-again, that currently the legal and illegal trade are so intertwined that they are functionally inseparable (as shown in the header image). This was reaffirmed in a recent report by South African based EMS Foundation and in collaboration with Ban Animal Trading.

There is a way to modernise CITES to make it relevant to current trade conditions, and resource it appropriately so it can be more effective. If done correctly, this will allow the legal and illegal trade to be better decoupled.

In the first instance, this means:

- Modernise CITES (currently it is so deeply flawed and under-resourced to the point it is useless)

- Global roll-out of electronic permit system to all 183 signatory parties by 2022 and CITES CoP19 in costa Rica.

- Preliminary work should start immediately to review the convention, this would include considering a reverse (positive) listing process, industry contributions/levy and how to factor in biosecurity needs. Initial discussions would start at SC73 and a Working Group could create the Terms of Reference.

- Decision at CITES CoP19 for comprehensive review of the Convention based on the Terms of Reference created

- To provide a sense of urgency, so the ‘can is no longer kicked down the road’, a moratorium could be placed on any new trade or increase in quotas for exiting trade until the review is complete and solutions have been found and implemented.

- Include wildlife and timber crime under the UN Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (of immediate effect)

Two more of Scanlon’s comments from the article:

“We have a whole framework for dealing with trade in species in terms of overexploitation.” Nature Needs More disagrees with this statement, after 45 years of operation, CITES has no proof of this to make this statement.

“The status quo ought not to be allowed to prevail”. On this we do agree.

On Monday evening I sat through a session of The Act #ForNature Global Online Forum hosted by the UN Environment Assembly. The session I chose to watch was Adapt to Thrive: transformational change for nature and business. If what was needed to fix the legal trade system was to be discussed, this was session (open meeting) where it would most likely be covered.

It wasn’t a surprise to hear the invited speakers talk about ‘purpose driven business’ and ‘aspirations’, all abstract concepts. The questions coming through from the observers around the world wanted details, action, pragmatism, something real and specific examples. The moderator, Jorge Laguna-Celis (Director, Governance Affairs, UNEP) tried to reassure the audience at the end, that the Fifth Session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-5), in Nairobi in February 2021, would go into detail and focus on pragmatic action, but given there has been no evidence of any such action from business or regulators for the past 20 years, I wouldn’t bet on it; electronic permitting alone has been discussed for a decade with minimal progress, even though a system has been created.

We are living through an unprecedented period in human history where humanity has created existential threats to its own survival as well as the survival of millions of other species. We need to stop the perception management that legal trade is working and start making wholesale, systemic changes to stave off the looming catastrophe.