In April 2016, I wrote an article titled, Want To Know Why Conservation Is Failing? Read On….

In the article, I spoke about the negative implications of the specialist-expert mindset. Over decades, people working in conservation (and beyond) have been supported to hone their specialist expertise through research but the professional development needed to evolve a more strategic way of thinking is lacking in the sector. Yet specialists rarely make good problem solvers when dealing with complexity. Too many become perfectionists in their field but are unable to make links, unable to consider the consequences of their proposed solutions outside their immediate field of expertise. In short, they do depth but don’t exhibit a breadth of perspective.

To use an analogy from Vikram Mansharamani – Lecturer at Yale University – if we think in terms of a forest, organisations around the world have come to value expertise and, in so doing, have created a collection of individuals studying bark. There are many who have deeply studied its nooks, grooves, colouration, and texture. Few have developed the understanding that the bark is merely the outermost layer of a tree. Fewer still understand the tree is embedded in a forest.

The current, most obvious example of this narrow way of thinking comes from conservation’s growing acceptance of cryptocurrency donations to wildlife causes. Wildlife charities explain, “that donating cryptocurrency is a non-taxable action, meaning you do not owe capital gains tax on the appreciated amount and can deduct it on your taxes”, they continue by saying, “This makes Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency donations one of the most tax-efficient ways to support your favourite cause.”.

So why is this an issue?

1. Lack of transparency and regulation

Bitcoin, the world’s largest digital currency, and other crypto ownership cannot be traced by a country’s central bank or law enforcement, making them difficult to regulate. This is about keeping trade opaque and customers invisible. No surprise that cryptocurrencies are loved by international crime networks. Cryptocurrencies are the logical extension of secrecy jurisdictions for tax avoidance and concealing ownership.

Although using blockchain technology is often stated to enable increased transparency, because all transactions are traceable by everyone with a copy of the blockchain and because transactions have to be verified to be included on the blockchain, whether or not this increases transparency depends entirely on how the specific blockchain is designed. Pretty much all cryptocurrencies designed using blockchain technology conceal ownership of tokens in the same way Bitcoin does. This can also be applied to anything else that is recorded on a blockchain. So evidence shows, blockchain does not necessarily equal transparency.

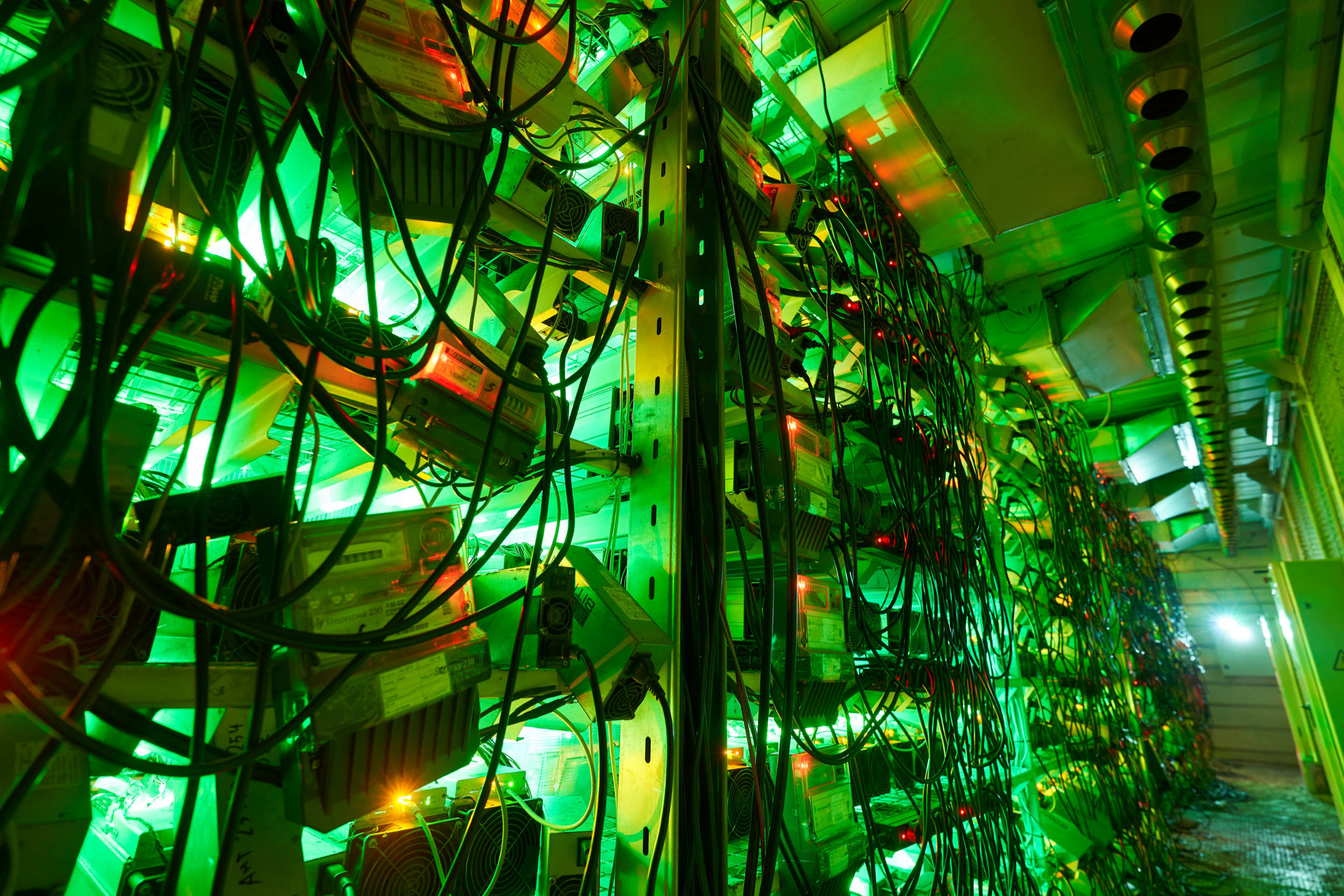

2. Cryptocurrencies are power hungry

Cryptocurrencies are terrible for the environment if they are designed like Bitcoin. The energy use to mine new Bitcoin is massive. Bitcoin may soon consume over 200 terrawatt hours (TWh) of electricity annually, according to a new study; almost 10 times more than Google, Microsoft and Facebook combined. Bitcoin alone already uses more electricity than some nations and the majority of the electricity consumed by cryptocurrencies is powered by fossil fuels (the rest is mostly hydropower).

Bitcoin is so power hungry that mothballed fossil-fuel power plants are being purchased and brought back online by crypto miners. Similarly, the need for space for mining racks mean they are purchasing anything from old factories to airplane hangars.

So, why are these cryptocurrencies so inefficient?

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies use blockchain. A blockchain is a distributed database in which EVERY miner (and anybody can be a miner) holds a copy of EVERY transaction; for the Bitcoin community, Bitcoin’s inefficiency is the feature, not the bug. In this situation you don’t need central authority to verify that the transaction is valid and when you don’t have a central authority a system is difficult to monitor and regulate. In addition, ownership of a bitcoin is verified via a private key that is only known to the owner. The bitcoin address can be public, as without the private key, knowledge of the bitcoin address alone is insufficient to access it. If the private key is lost, so is the bitcoin it is associated with. To transact in Bitcoin, you only need the private key, no personal information is required.

For comparison, in the case of credit cards only the card issuer and card provider keep copies of transactions. If you ‘find’ a credit card, the name of the owner is printed on it. If you ‘find’ a Bitcoin private key, you can use it, but you still don’t know who the owner is. This degree of concealed ownership is only broken if the owner uses a Bitcoin exchange, which is increasingly required by law in some countries to collect personal information in a belated push for regulation.

“[All this inefficiency is] what gives Bitcoin its value,” said cryptocurrency researcher Peter Howson from Northumbria University. “If we say, ‘Oh, let’s make it efficient’, you’re just saying, ‘Let’s reduce the value of a Bitcoin’ — why would you do that?”

This example alone highlights why it is astonishing that so few climate activists are speaking out about the growing legitimacy of cryptocurrencies. Banks are opening up to cryptocurrency, as are superfunds and even entire countries; bitcoin gained the status of legal tender within El Salvador from 7 September 2021. While Bitcoin has the status of legal tender within El Salvador, the government cannot issue it (Bitcoin can only be mined, not issued); this deprives the government of currency sovereignty, which severely constrains its economic and social actions. Which makes you wonder, why a government would do this?

3. Who can ‘issue’ a new cryptocurrency?

Anyone can ‘issue’ a new cryptocurrency. Creation of cryptocurrencies is unregulated, opening the door to plenty of scams, pyramid schemes and fraud. Cryptocurrencies are not actually currencies, since they are not legal tender (you can’t pay your taxes with them). They are just digital ‘tokens’. What makes them interesting to people is that because they can ‘invest’ in these tokens, they are prepared to pay real money for them (this is the same as with any in-game currency). In reality, they are simply objects of speculation.

In addition, the exchanges that convert cryptocurrency for real money are also completely unregulated and subject to frequent hacks, where all ‘wallets’ are stolen. Lack of regulation means that sometimes they are stolen by the creators of the exchange. Both the speculation and the lack of regulation and oversight make cryptocurrencies extremely volatile; their value fluctuate wildly.

Given all this, I come back to why would conservation charities accept and promote a system that is designed for secrecy, lack of regulation, fraud and untraceable ownership? Indeed, why would you legitimize the very strategies used by wildlife traffickers? Why, on top of that, would you support cryptocurrencies that drive fossil fuel use and CO2 emissions through their massive energy use (which comes mostly from cheap coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel)?

Two examples that are red flags and linked to the legal wildlife trade:

1. Back to El Salvador. In recent days, El Salvador President Nayib Bukele said, ‘It’s game over for the dollar, Bitcoin is the future’, pushing back on those who have raised questions about El Salvador’s decision of making Bitcoin legal tender.

At the same time, El Salvador is the world’s largest exporter of live animals into the legal trade. The legal trade is regulated by CITES through a (mostly) paper-based permit system that already makes it laughably easy to launder illegal wildlife into the legal marketplace.

So, when the world’s largest exporter of endangered and exotic live animals adopts Bitcoin as legal tender, it will make it even easier to corrupt the legal trade system and will enable the illegal trade to flourish in the country and through its borders.

2. Modernising the CITES trade permit and database. There has been some push from agencies interested in the legal trade in endangered species to move the CITES permit system onto blockchain, including from The World Trade Organisation. This is completely unnecessary and a distraction from getting rapid adoption of the eCITES BaseSolution, which is based on a QR Code system to verify permits. The eCITES BaseSolution already allows real-time permit verification anywhere in the world with a smartphone. This is particularly beneficial in developing countries, given the low infrastructure costs of using QR codes and smartphone technology. In addition, its centralised structure is much better suited to CITES permitting (with a centralised rule base). Centralisation in this case enables greater levels of scrutiny and transparency, which is what is desperately needed for the legal trade in endangered species. The risk that eCITES permits and reports are tampered with is relatively low given that it is hosted by UNCTAD and UNCTAD follows the full UN cybersecurity guidelines.

A final worrying trend is that Bitcoin is much more popular with people in the 18-34 age group, covering Gen Z and the millennials. This group is keenly aware of climate change and the potential repercussions for them in the near future. So why would they think of Bitcoin as a ‘financial innovation’ and ‘an asset’? This lack of curiosity about Bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies more broadly, is extremely worrying; the fact that it is not an asset (with any intrinsic value or return) and not a currency is not exactly hidden from the public. There have also been countless articles about the energy use and CO2 emissions associated with Bitcoin.

If the age group that will soon inherit the disastrous consequences of our overconsuming Western lifestyle cannot make the simplest link between Bitcoin and its environmental consequences, that is pretty tragic. Especially since Bitcoin is DESIGNED to use ever more energy as it becomes more popular (at least until all Bitcoins have been mined)!

In one recent survey, 42% of those in the 18-34 age group said they are likely to buy Bitcoin within the next 5 years. With 90% of all possible Bitcoin having already been mined, only around 2million remain. To slow down mining, the mathematical problem the miners have to solve gets ever more difficult, requiring more computing power and more energy. Projections show this will reach 300 TWh by 2024.

This sort of disconnect, between watching the climate and biodiversity disasters unfold and making decisions to make it worse is quite staggering. You can’t worry about the environment and then buy cryptocurrency! It is the same disconnect observed between getting anxious and depressed about the pandemic and not making the link to the legal trade in endangered species and then jumping online to get your dopamine fix from buying more stuff.

This compartmentalised approach to thinking, the inability to consider the consequences outside your immediate field of expertise and the lack of breadth of perspective is extremely worrying given the lack of time left to implement effective solutions. The world has ignored the climate and biodiversity crisis for far too long to now rely on such narrow thinking and shallow solutions.

The lockdowns and the slower pace of the last two years have, in theory, provided more of us the time to invest in understanding both political and corporate agendas and power plays. Organisations dealing with the climate crisis and extinction crisis need the strategic intuition to recognise (covert) agendas and deal with them surgically. They need to be able to influence stakeholders to tackle systemic priorities, not symptoms, no matter how difficult.

Seeing climate activists ignoring the growing legitimacy of cryptocurrencies and worse still, some conservation agencies actively asking for crypto donations is truly dispiriting given this need for strategic thinking and systemic change. I sincerely hope that the conservation sector will be smart enough to dump cryptocurrency donations quickly and stop prioritising donations, ‘by any means’, over the need to get real results for wildlife and the natural world.