Zimbabwe has indicated that it is planning to present a case to CITES, CoP19 in Panama later this year, to allow (another) one-off sale of its ivory stockpile. The country is also rallying its allies (Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia) to support the push to open up the ivory trade. This, together with a recent image of Japan’s ambassador to Zimbabwe photographed holding a large elephant tusk in Harare, has understandably caused concern for those opposed to such one-off sales.

Nature Needs More believes that CITES should be a conservation-based convention, where the precautionary principle is used (in the form of a reverse listing process) as a basis for making any decisions about the legal trade. For now we have to accept that the agreed CITES ideology is a trade-based, with signatory governments and corporate conservation organisations alike supporting the unproven but ‘so called’ sustainable use model. Under the current model all trade is accepted and the burden of proof to demonstrate that trade is negatively effecting a species in the main relies on donations from philanthropists.

It is in businesses interest to invest in the illusion of sustainability and too many conservation stakeholders have unquestionably backed the sustainable use model. While they parrot their mantra of an evidence-based approach to conservation, they provide no evidence of what constitutes a sustainable off-take. As a result, we investigate Zimbabwe’s request for more trade in ivory under the currently accepted trade ideology. Even using the accepted model there is significant evidence to show why this one-off sale should not be allowed.

An analysis of the trade in ‘Elephantidae’ specimens (which covers everything – ivory, skins, feet, ears, trophies etc) from Zimbabwe to a number of countries worldwide, show the most basic reconciliations cannot be made. The trade information investigated covers the period 2010 to 2019. This time frame was used because over this decade poaching of African elephants was happening at an industrial scale, with reports stating an elephant was killed once every 15 minutes.

In Zimbabwe, elephant herds were being killed by cyanide poisoning as they went to drink at waterholes and cyanide was also found infused into oranges, left for elephants to eat.

So given the global attention that the industrial scale slaughter of elephants was receiving during this time, you would believe that any nation (exporters or importers) who want the legal trade in elephant body parts to remain would be diligent in doing everything they needed to do to prove that no illegally sourced elephant body parts were entering the legal supply chain. So let’s check!

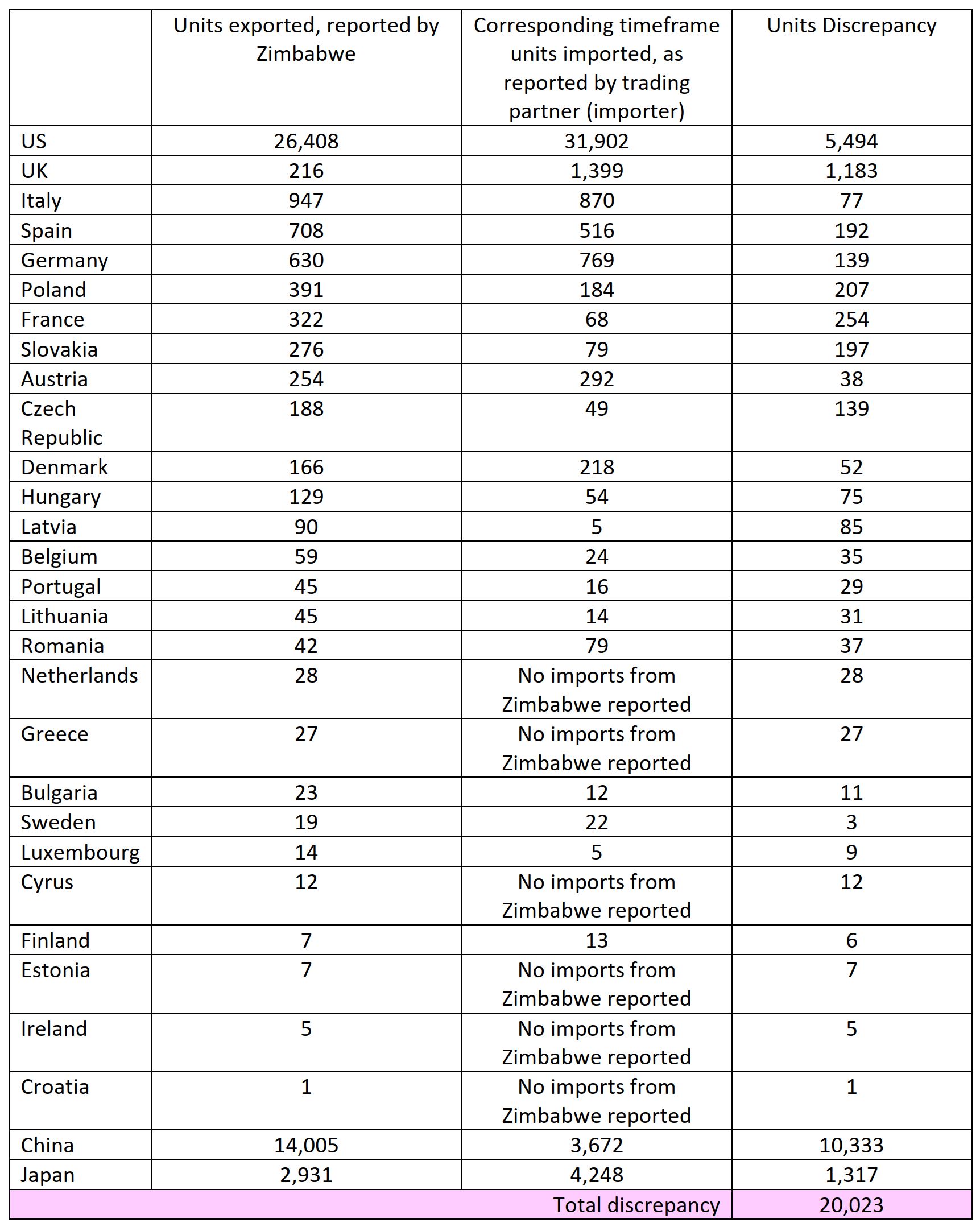

For the time frame 2010 to 2019, can export and import data be reconciled? The table below details the number of ‘Elephantidae’ specimens Zimbabwe’s CITES trade export permits show the country exported and details how much Zimbabwe stated it was sending to each of the countries listed. For the same time frame, the corresponding import data, from each country, shows the number of ‘Elephantidae’ specimens the country reports to have imported from Zimbabwe.

There is a discrepancy of 20,023 units of ‘Elephantidae’ specimens. So where did those missing 20,023 units of Elephantidae specimens go?

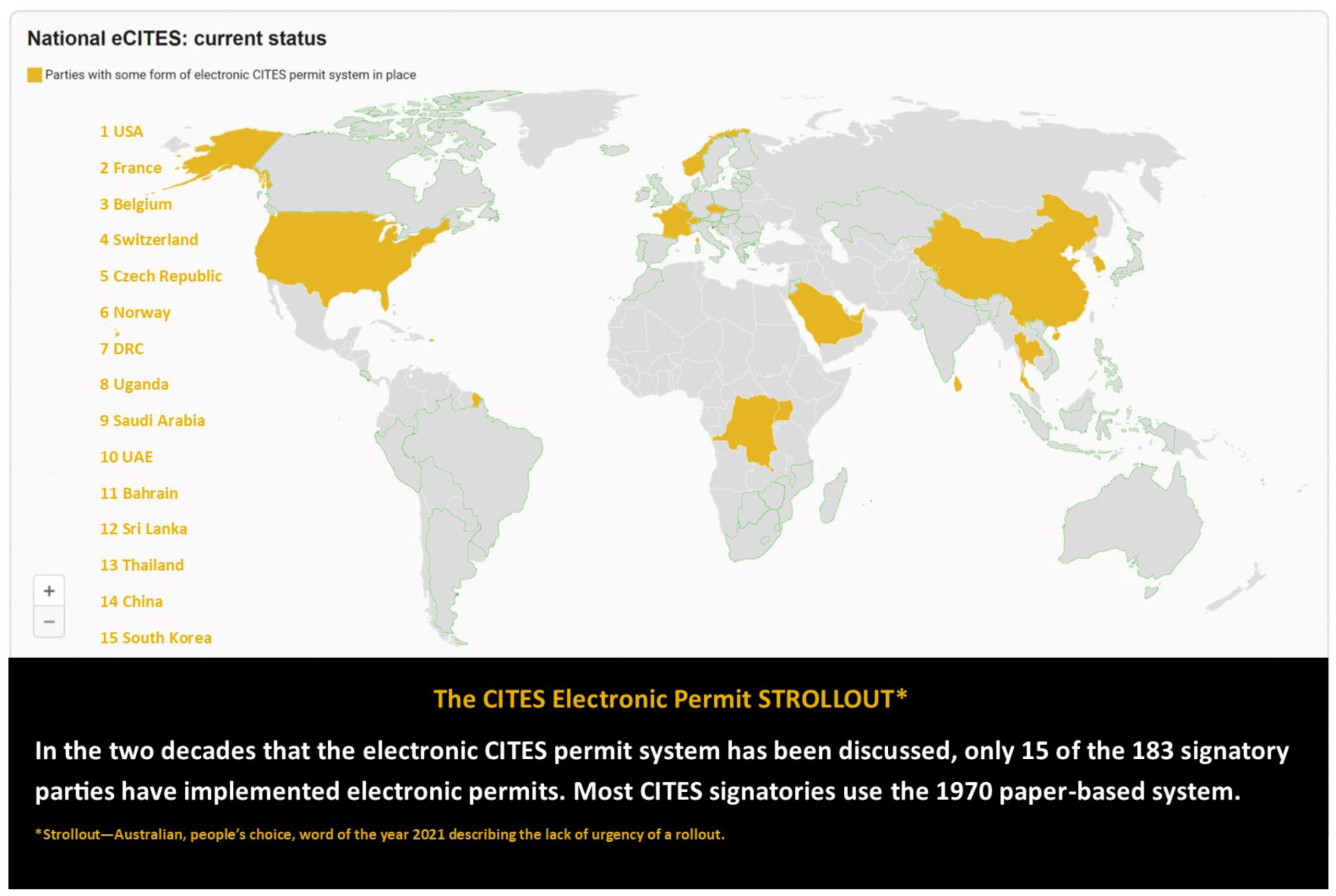

The current CITES, 1970s paper-based system makes even the most basic reconciliation of trade simply impossible. As a result, any country can make claims about sustainability that cannot be proven or disproved. And any country’s claim of having a well-managed legal trade in endangered species cannot be proven or disproved. And, any business can make claims about sustainability that cannot be proven or disproved.

Until this shocking lack of supply chain transparency is decisively tackled, no more trade should be allowed, including ‘one-off’ sales of stockpiles.

Let’s be clear that NONE of the countries indicated in these recent reports, wanting the sale of ivory or ‘hinting’ that they may support the push for this sale, have implemented a CITES electronic permit system. Given this example is about the ivory trade and the key profiteer from this trade is the antiques and auction house industry, the industry body hasn’t rallied its members to put their hands in their very deep and full pockets to provide Zimbabwe with the US$150,000 needed to implement the eCITES Base Solution in the country.

In the two decades it has been discussed, only 15 CITES signatory parties (listed) have implemented an electronic system; a pace we now call the CITES ePermit strollout.

Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Japan while indicating they are planning to move from the paper to an electronic permit system have not provided a timeline for when this will be completed.

Zimbabwe has also sought support from the European Union for this sale of ivory, which is why the trade to the EU was part of this analysis. Only three countries, in the EU-27 block, have implemented CITES electronic permits, France, Belgium and the Czech Republic. In speaking to representatives of some European countries, they handball the fact that nothing has been done domestically back to the EU saying, “the European union is developing an EU permitting system”, implying that this will be done centrally and implicitly absolving member states from doing anything now.

The current trade regulation and monitoring is simply a disgrace, obsolete and not fit for purpose. It provides the loopholes for laundering illegal items into the legal supply chains. Countries pushing for more/new trade in ivory should instead focus on closing these loopholes, not on self-serving attempts to profit from a trade that will also open up new avenues for traffickers.

Are there any signs of hope that the mindset is changing when it comes to the CITES trade and permitting system? Possibly. A paper published in August 2021 titled, Trading Animal Lives: Ten Tricky Issues on the Road to Protecting Commodified Wild Animals; issue 10 explores why a positive list (another term for reverse listing) might work better than a negative one.

It concludes:

“If the burden of proof lies primarily on conservationists to demonstrate that trade is negatively affecting a given species before it is afforded the legal protection required to prevent its extinction, and given the general inadequacy of monitoring, drastic overexploitation may occur long before any checks can be effective…

….At a time of unprecedented human population impact, technological advancement and associated globalization, this situation calls for the application of a positive list, whereby for a species to be listed as saleable the trader must first demonstrate that trade is not detrimental to its conservation. Starting from a presumption of wildlife protection, the onus might more appropriately be put on would-be commoditisers to provide the first evidence of the trade’s sustainability, humaneness, and safety, not vice versa.“

An Australian Update#

In 2019, at CITES CoP18, Australia announced that it would close the domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn in the country. This still has not been done.

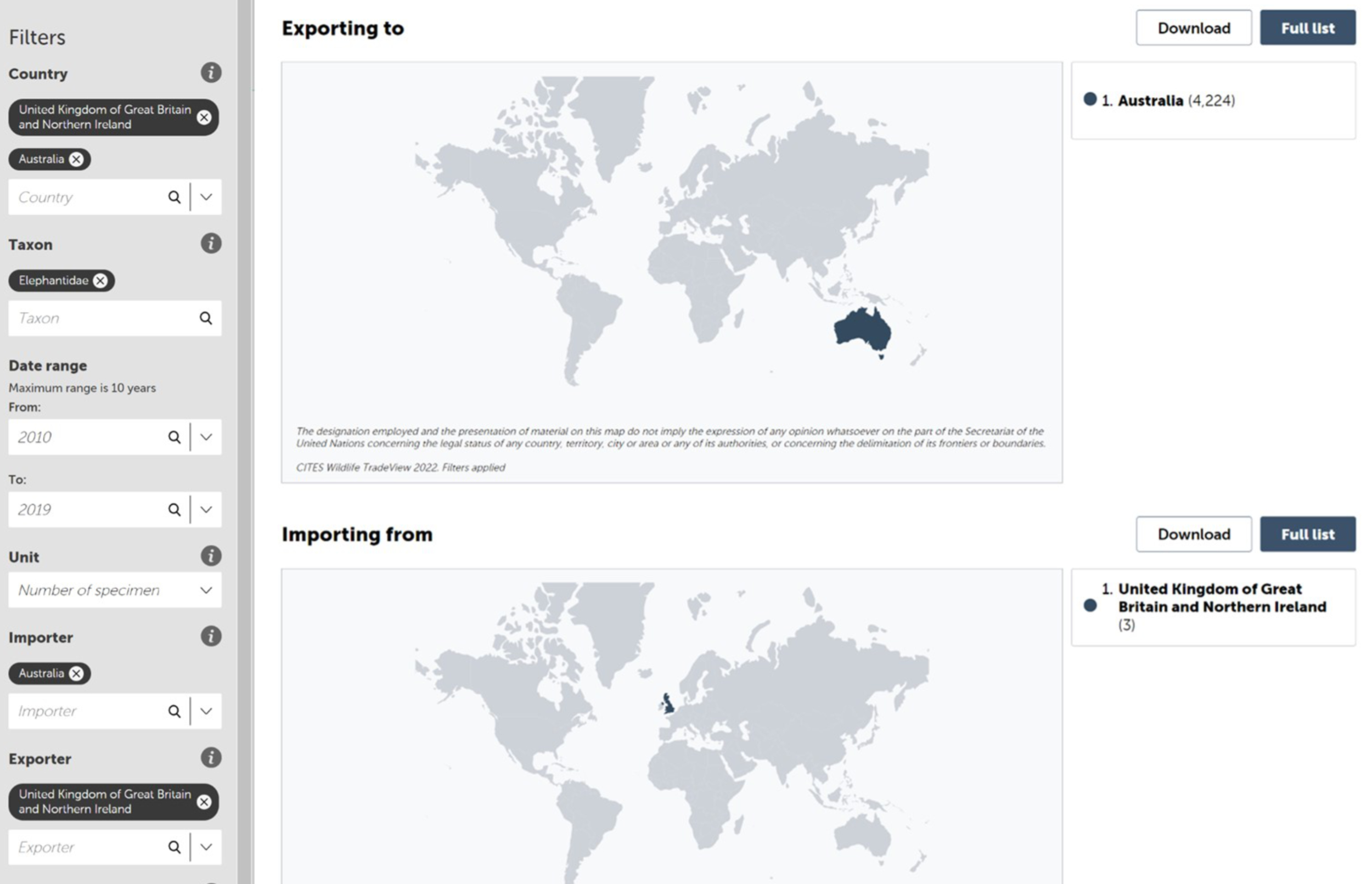

The trade ban was announced after a bipartisan parliamentary committee recommended a national ban on the domestic trade of elephant ivory and rhino horn in 2018. There were many factors presented to the joint parliamentary committee investigating the domestic trade as to why it should be banned. Not least was the inability to reconcile CITES permit export/import data. In 2018, CITES trade data in Elephantidae specimens was presented to the committee. The data highlighted the trade between the UK and Australia from 2010 to 2016.

Since the launch of the CITES Wildlife TradeView website, we expanded the analysis to look at the same trade route from 2010 to 2019.

The discrepancy of 2,950 ‘units’ found in the 2010 – 2016 trade, had grown to 4,221 ‘units’ for the 2010 – 2019 trade.

No one has been able to explain where the missing ‘units’ are, even though Australia is one of the few CITES signatories to have mandatory import permits. Australia must ignore the ongoing lobbying from the antiques and auction house industry and follow through on its 2019 announcement to close the domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn.