It is time for conservation organisations to stop lending their brands to industry greenwashing. There are many examples of this, but since it is in the news, let’s focus on the illegal online trade in endangered species.

Launched in 2018, the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online has three conservation organisations, WWF, TRAFFIC and IFAW, who are stated to be the convenors of the coalition. The group includes Facebook (Meta), Google, ebay, Etsy, Instagram, Microsoft, TikTok, Alibaba and many more:

Early after its launch, the coalition stated its goal was to cut the illegal online trade by 80% by 2020.

Their 2021 progress report states that, as a group, they removed 11 million posts and listings of illegal wildlife for sale but did not say what percentage of the total illegal online trade that amounts to. WWF and TRAFFIC love their ‘evidence-based’ approach mantra, using it to try to differentiate themselves from the small, often volunteer run, organisations that have evolved to step into the leadership void on the trade in endangered species, and ‘genuinely’ speak truth to power.

If we apply the yardstick of an evidence-based approach to the 2021 progress report, does the report stand up? – Well, no. Aside from the number of removed posts provided without context, it highlights the number of staff who received training, the number of listings reported by citizens and the ‘number of impressions’ of the user awareness campaigns. There is zero information on how these measures are in any way connected to ‘cutting the illegal online trade by 80%’.

So, it should come as no surprise that the global campaign group Avaaz reported that they found tiger cubs, leopards, ocelots, African grey parrots and the world’s smallest monkey, the pygmy marmoset, among the endangered animals for sale on Facebook pages and public groups. “Traffickers do not shy away from listing their goods for sale in public groups, nor from including their phone numbers in their posts,” said Ruth Delbaere, senior legal campaigner at Avaaz. “On Facebook wildlife trafficking takes place in broad daylight.”

This lack of secrecy suggests the trade on Facebook remains largely risk-free, thanks to the anonymity Facebook offers to sellers and buyers. The traffickers are so unconcerned that they openly named their Facebook pages, such as one called “Wildlife Trade, Pangolin Scale & Rhino Horn” which invited bidders on their animals and posted a photo of a pangolin in a cage. Again, let’s compare this to the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online 2021 progress report, which states:

It seems that Pangolin Scale & Rhino Horn weren’t a part of these 2,500 known search terms!

In another example of just how easy it is to buy endangered species illegally online, VICE World News’ own investigation found it took them less than 24 hours to order an endangered tiger on Facebook.

The ease of wildlife trafficking online led Raúl Grijalva, Democratic congressman and chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources to say “Not only does Facebook know that wildlife trafficking is thriving on their platform – they have known about it for years. Yet, they continue to blatantly ignore the problem – or worse – enable it, violating even their own self-professed stand against criminal activity and physical harm to animals.”.

And it isn’t only Facebook, as it isn’t hard to find images or videos of the illegal pet trade on TikTok or Instagram or rhino horn and elephant ivory beads on Etsy.

All this leads to the question, should global conservation organisations such as WWF, IFAW and TRAFFIC, lend their brands so easily to business?

WWF, in particular, has a history of ‘partnering’ with industry, providing an air of legitimacy to initiatives. Yet for decades no real progress has been made in slowing the wildlife trade, in fact it has been going in the opposite direction.

The 2017 World Customs Union Illegal Trade Report estimated the profit from the illegal trade in flora and fauna to be between US$91- 258 billion per year. The report stated that according to the United Nations Environment Programme, this trade is growing at 2-3 times the pace of the global economy. Where is the evidence to show that conservation organisations, from WWF to the IUCN, ‘partnering’ business is driving down the illegal trade?

The industrial scale of biodiversity loss means ALL forms of greenwashing must be interrogated and exposed.

What is the point of the conservation convenors setting a clear, measurable goal – reducing the illegal online trade in wildlife by 80% by 2020 – then providing no useful reporting on the progress towards the goal? Has the illegal online trade in endangered species been reduced at all? Maybe it has even increased? We are left guessing because of the frankly useless information being reported. It is yet another case of too much noise and too little substance.

So back to my earlier question, is it time for conservation organisations to stop lending their brands to industry greenwashing? They are lucky that currently too few people are paying attention and questioning conservation’s complicit behaviour in greenwashing. But this will change.

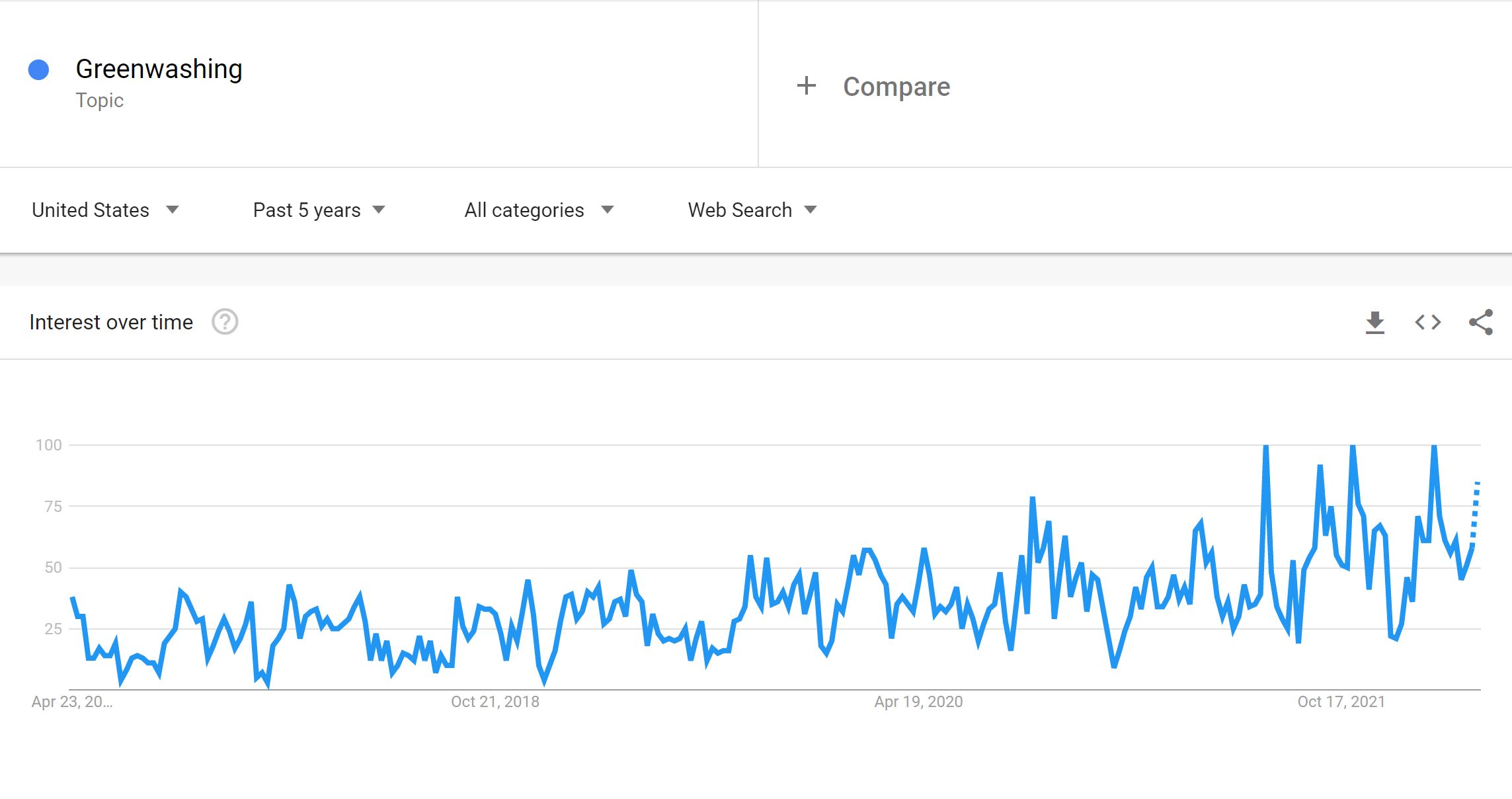

Ironically, according to Google Trends, over the last 5 years the searches and discussions on the topic of ‘greenwashing’ are consistently growing in popularity, including the topic of environmental and social corporate governance (ESGs):

The scrutiny of companies ESG statements is increasing. With too many ESG claims simply not stacking up there is a growing chorus of concern over greenwashing, as worry over biointegrity (and climate change) intensifies.

The UN has made it clear that there are only 10 years left to save the world’s biodiversity from mass extinction. Undoubtedly some of the people working in corporate conservation, who have made the decision to collaborate with businesses and industries on these poorly designed and ineffective projects will be long retired by 2030, their reputations saved. But for those who will be working in the conservation sector beyond 2030, ask yourself, can you really use a plausible deniability strategy when you are challenged about not speaking truth to power and lending your personal brand to companies and industries to help greenwash their activities which have driven the extinction crisis?

When the time comes, human nature will mean that people will look for someone to blame. Consumers will want to pretend “we didn’t know”, to absolve themselves. They will say that they trusted the large conservation organisations and they are ‘shocked’ that they were complicit in misrepresenting the ecological impact of the brand, product or company/industry initiative.

As they look for ways to feel better about their own consumption behaviour that has contributed to the extinction crisis, they will say that historic greenwashing practices undermined their attempts to make their consuming behaviour, their lives and their homes more sustainable to prevent biodiversity loss and environmental damage.

To large conservation, you may have 10 years to prepare your case for plausible deniability.