It is no secret that the South African Government has approved the submission to the next CITES conference, scheduled to take place in 2016 in South Africa, to introduce a regulated international trade in rhino horn. Backing this approach are a number of pro-trade lobby groups. Even through the commonly held belief is that it is unlikely to be permitted, pro-trade trade groups will spend the time leading up to the October 2016 conference trying to prove that a legalised trade in rhino horn is the only way to save the animal.

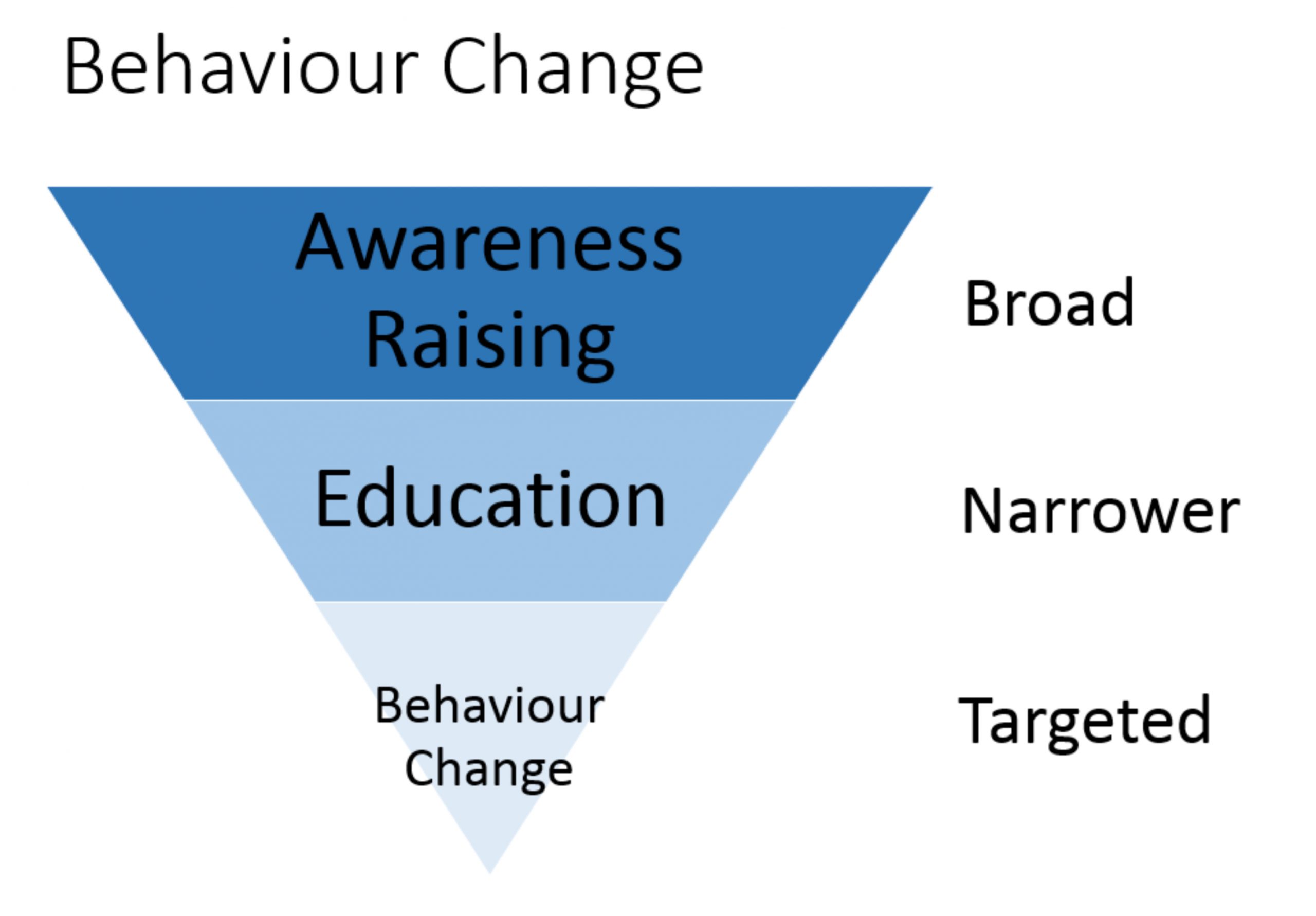

One of the final things to stand in their way is a successful demand reduction approach to stop rhino poaching. The conservation industry has an 18 month time window to demonstrate the effectiveness of demand reduction strategies. The problem is that the conservation industry doesn’t have extensive experience in researching, designing and producing demand reduction initiatives. Over the years they have run:

- Fantastic awareness raising advertising campaigns

- Good quality education strategies

Currently too many awareness raising and education strategies are being packaged and sold to the public as demand reduction and they are not. If this is not recognised it has the potential to provide the pro-trade lobby with ‘evidence’ that demand reduction strategies haven’t worked to save the rhino. It is imperative that the conservation industry in its naivety of what a demand reduction campaign really is doesn’t play into this.

To be effective, a demand reduction campaign needs to create an immediate change in behaviour in the current groups of people purchasing and using genuine rhino horn. In recent months we have seen projects targeting primary and secondary school children in Asia being called demand reduction campaigns. They may, through education, ensure that these children don’t become the next generation of users in 20 years’ time, but they are not demand reduction campaigns.

To reiterate, demand reduction requires directly targeting the current users of genuine rhino horn and in such a way that a behaviour change will result within 6-12 months. A good example from another industry is the plain packaging of cigarettes introduced in Australia in December 2012 – it targets the uptake of cigarette smoking by young people, which many prior studies had shown to be heavily influenced by branding.

In addition, the conservation industry has committed itself to a focus on higher values when seeking behaviour change, as outlined in the Common Cause framework. This is correct in the sense that when we are looking for long-term, sustainable behaviour change we cannot rely on fear, greed or ego. At the same time this approach presumes that the users of illegal wildlife products are open to such an approach and that they share a set of higher values that a campaign can appeal to.

The problem is, this isn’t necessarily the case, as outlined in Values Development, Behaviour Change and Conservation. Instead, the commitment should be to using the most effective strategy to save the animal in question, which means understanding the underlying motivations of the users and targeting the demand based on those insights.

Some agencies are starting and have ‘dipped their toe in the water’ of social psychology and behavioural economics. But there is still the belief that all messages should be positive, that messages shouldn’t upset people and they should appeal to people’s higher values. The assumption is that people learn and change when they are positively engaged. This pervasive mindset will limit the effectiveness of demand reduction campaigns.

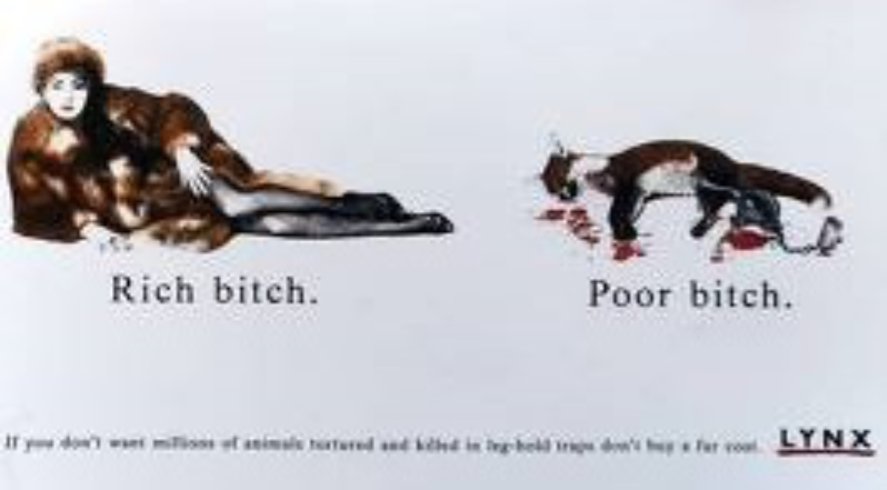

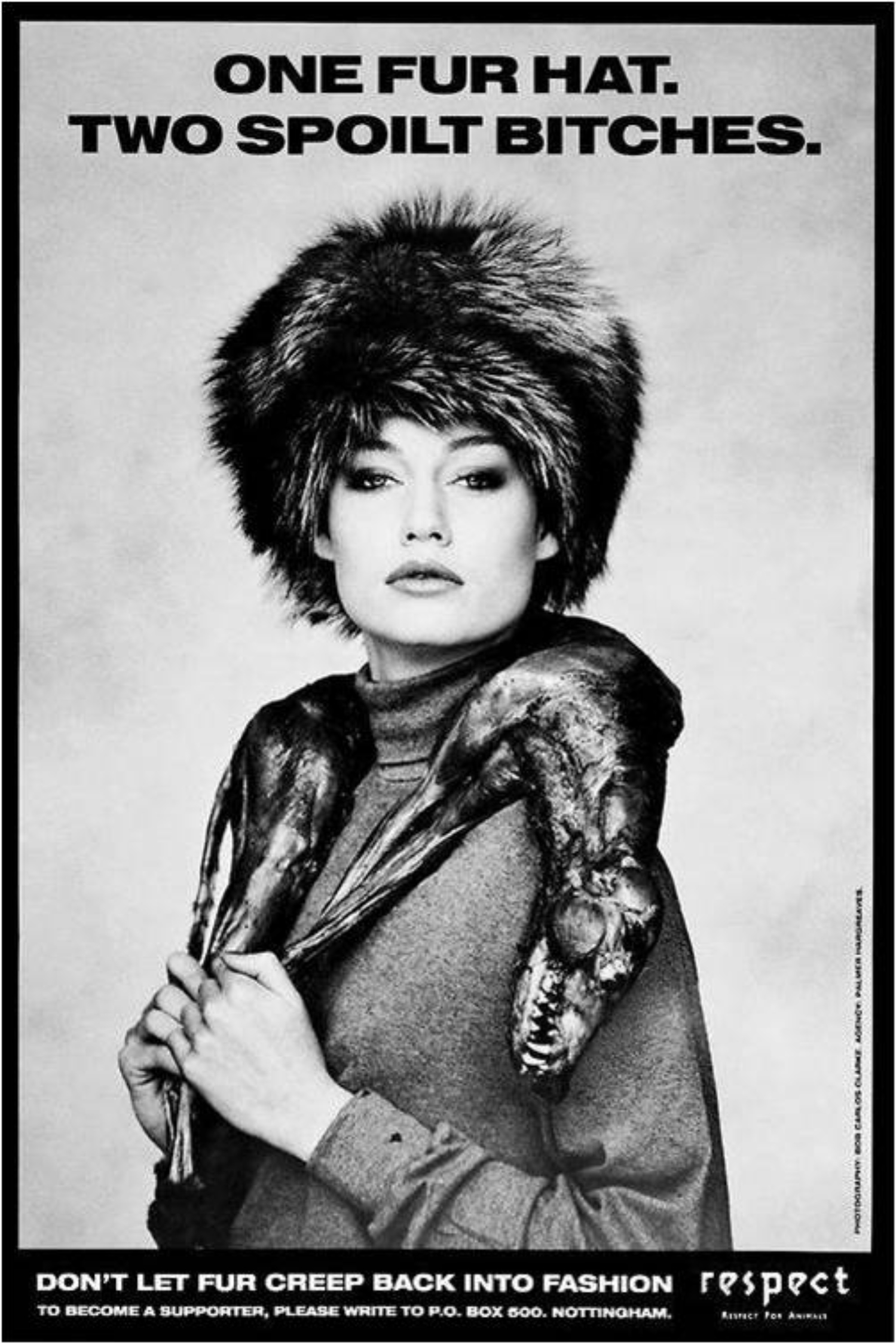

I still believe that one of the most effective demand reduction campaigns I have seen was the Lynx (now Respect for Animals) anti-fur campaign of the 1980s. It would not pass the higher values test set out in the Common Cause report and handbook. Instead, it goes after the person’s ego, an approach explicitly ruled out by the Common Cause framework. Yet the campaign was highly successful, even in the long term.

In reality, for behaviour change messages to be effective with the actual user they need to elicit an immediate emotional response in the person; to do this they are generally controversial.

The Lynx campaign was using social psychology intuitively and before most of the science was fully established. These campaigns were targeted for being sexist, which they are not. They simply target the people wearing fur coats and, in the main, they were women.

As you can see from the posters, this campaign does not appeal to a higher set of values, instead it directly undermines the person’s ego and elicits pain and insecurity. The visuals show people representative of the core user group – wealthy women wearing fur.

The pain is linked to being called a ‘dumb animal’, a ‘rich bitch’ and ‘spoilt bitch’. The insecurity comes from the fear of being rejected by your peer group or the group you aspire to, who have stopped wearing fur.

The background behind the model used here is explained in: https://natureneedsmore.org/by-harnessing-humans-reptilian-brain-we-have-a-chance-to-save-the-rhino/

The anti-fur campaign of the 1980s worked quickly and decisively. What is surprising is that in the intervening years, as the demand for fur has begun to rise, this type of strategy was not adopted by the large conservation organisations that have significant resources. Again it is the small organisations, such as Respect for Animals, who have revived this type of approach.

Even historical campaigns such as the murderous millinery campaign which targeted the ‘plume boom’ driving exotic birds to extinction used images that triggered the fear of being rejected by the fashionable ladies of the time who had stopped wearing hats with exotic feathers and frowned on women who continued to do so. Today this means that a lot of exotic bird species are still in existence that were on the verge of extinction for a useless fashion trend.

So what does this all mean for the rhino? It means that at some point in the not too distant future we should expect the pro-trade lobby to say ‘Look at how much money has been spent on demand reduction and what is the result?’ If 95% of what has been spent has gone to campaigns that shouldn’t be termed demand reduction or are ‘too nice’ because they only appeal to a higher set of values the users don’t share, this could provide the pro-trade lobby with ammunition to push for a legalisation of trade.

It is time for the conservation industry to educate itself about what really constitutes a demand reduction campaign and be courageous to create the campaign that will achieve the necessary behaviour change in the current user groups, even if it doesn’t sit comfortably with their beliefs and values.

In addition the conservation industry doesn’t want to upset the sensitivities of its donors. So in turn it is imperative that donors are similarly educated and emotionally resilient to support a campaign that triggers their personal discomfort, but will actually work with the users targeted.

These are the views of writer: Dr. Lynn Johnson, Founder, Breaking the Brand