Two tragic things happened in the last month and taken together they highlight the lack of courage global conservation organisations and academics have shown in both exposing, and trying to fix, the structural weaknesses of the system that regulates the global, industrial trade in over 40,000 endangered and exotic species.

First, in a submission document to CITES CoP20, the organisation’s leadership acknowledges, “The current mode of work is no longer viable”, continuing, “The time for action is now, to safeguard the Convention’s integrity and effectiveness”. A concern that Nature Needs More contacted the CITES leadership about in 2018.

The second is that well-known global conservation organisations have lent their brands to help small, private sector entities step into the void created by decades of undermining the CITES regulator. Too many voluntary monitoring and certification schemes have been created in recent years, instead of better improving and better resourcing mandated regulation. Privatised voluntary governance undermines the ability to hold both businesses and governments to account for their desire for ‘growth and profits at any cost’; this ideology is the primary driver of biodiversity loss. These private voluntary schemes are a gift to companies who can cherry pick what they disclose to create the perception of supply chain transparency and sustainability.

Why would seemingly well-respected conservation organisations sell out the CITES regulator to support business greenwashing? For this, such organisations should be professionally ashamed and will never be able to apologise enough for their legacies of selling out wild species, once the scandal of the unchecked legal trade in endangered and exotic species is finally exposed.

Over decades academics and conservation bodies have ignored how the CITES needed to evolve to respond to changing trade conditions and ensure it remained effective in regulating the high volumes of commercial trade, valued at hundreds of billions of dollars annually. In backing voluntary governance schemes, they have sold out the one organisation that has a chance of saving the little that is left, just at the point it is openly asking for help.

CITES CoP20 is taking place in convention’s 50th year of coming into force. This should bring a level of scrutiny of the type, “After 50 years, has the CITES worked?”. Maybe it was with this in mind that the CITES leadership have admitted the regulator can no longer cope, in their submission with the misleading title, Enhancing the work and efficiency of the Convention through the permanent committees.

Admitting that the CITES regulator can’t cope is the simple and honest reality of a system set up to manage a few hundred species whose model didn’t evolve when the listings reached several thousand. Add to this, since the 1980s, like all other business regulators, the CITES has been undermined and impoverished. Big brand conservation hasn’t exposed this crisis or held any of the stakeholders to account.

The fact that the CITES leadership have made this admission should be positive. It opens the door for those who, for whatever reason, have shown a deep discomfort in exposing the weaknesses of the current system to step up and help with the needed modernisation. To instead focus their efforts on collaborating in private, voluntary governance schemes is spineless.

Over recent years, Nature Needs More has lobbied for the funds to modernise CITES and particularly the first step of a global roll out of electronic permitting. On several occasions I have had philanthropists say, “we can build a system, we know people in Silicon Valley”. My response each time was that the system is already built, we don’t need a private sector, decentralised system we simply need to roll out ASYCUDA eCITES to the 100+ countries that use the ASYCUDA customs system. Wealthy countries can create there own “single window” system, if they feel that they need it, but then they must cover the costs of ensuring their custom-built system is and remains interoperable with the central CITES system.

But a centrally monitored and managed permit system, created by a regulator, is not what people want to hear because it doesn’t fit with how they have been indoctrinated into free market ideology and the belief that private entities can do things better than government. There are numerous examples disproving this, from the privatised water management in the UK to the middle-men profiting from the pre-authorisation process for Medicare in the USA and the many useless carbon credit schemes.

But at some point, we must talk about the role of corporate conservation, particularly those in the executive roles, in actively supporting greenwashing of the legal trade in wild species. Their clinical sidestepping of the legal trade, to focus solely on trafficking, has mislead the public about the fact that the key regulator hasn’t received the investments and upgrades needed to monitor this trade, which is at least 10 times larger than the illicit trade. The CITES trade system lives in a 1970s pre-digital world, wide open to fraudulent use, to manage one of the most lucrative trades in the world.

By ignoring what is needed to ensure that the CITES regulator can do its job, while in parallel lending their brands to private entities who can never do what a modernised CITES regulator would be capable of, they continue to silently implement the free market ideology’s bidding. As one person said recently, when deciding they could no longer work in the system creating the harm, “No job is entirely ‘harmless’ but there is a threshold of how much harm one is willing to accept in exchange for a paycheck. It’s an individual decision”.

When we are collectively ready to admit that the scale of biodiversity loss is a global business scandal, and only mandated government regulation and a modernised CITES can curb this unchecked excess, then can we acknowledge the most important document submitted to CITES CoP20 is one that admits, “The current situation [in the CITES] has brought us to a critical point, where addressing the increasing demands and expectations of every issue simultaneously has already gone beyond the capability of the Convention’s operational framework. The current mode of work is no longer viable or sustainable.”.

If this is not addressed, the document states, “we may have expanded beyond capacity [to deliver] the official mandate of the convention, which is to regulate trade in species and focus on topics for which no other appropriate competent bodies exist.”, continuing, “Urgent action is therefore required to ensure that the essential function of the Convention remains effective into the future”.

Tragically and tellingly, it seems like the CITES leadership knew that its courageous admission would not lead to the type of support that it truly needs. It pre-empted the lack of adequate response by proposing the use of a “prioritisation matrix” and to explore “innovative ways” to, “focus to the core work [and] enabling us to use our scarce resources more effectively”.

The reality is that the limited funds and energy will become even more focused than they already are on iconic species, at the expense of the less sexy but often more exploited ones. Similarly, funds and energy would also continue to be focused on the countries and regions who shout the loudest. A ‘prioritisation matrix’ and ‘innovative ways to use scarce resources’ is the last thing the CITES needs!

In the document, the CITES leadership states, “The time for action is now, to safeguard the Convention’s integrity and effectiveness”. I agree with this statement and commend the CITES team for documenting it.

After examining CITES in detail since 2017, we concluded that the convention in its current form had become unworkable. Not just because it lists over 40,000 species, but because the model of regulation underpinning it (negative listing – trade until there is proof that trade is unsustainable) cannot work in an era of rapid biodiversity loss and over 1 million species threatened with extinction. We detailed pragmatic and real solutions (in the linked reports) on how to modernise the CITES so it can cope with current and future global trade volumes.

If we collectively agree with the landmark 2019 IPBES Global Assessment report, which confirmed that trade is the biggest extinction risk for marine species and the second biggest risk for terrestrial and freshwater species, then we either need to ban trade or invest in a modern regulator that can transparently validate that all trade is legal and sustainable. And let’s remember, this is Target 5 – all trade is sustainable, legal and safe by 2030 – of the KMGBF (CBD), which all countries in the world bar the USA have signed on to. Under the current system of extraction, monitoring and regulation, Nature Needs More can with 100% certainly say that there is no chance of achieving Target 5 by its goal date of 2030.

This is even more certain if global conservation brands put their names behind small, private entities and ignore this admission from the CITES leadership. CITES will simply continue to wither away, while unsustainable exploitation – some might say looting – of the little that is left continues. This is tragic because of what is pointed out in the document, “that the CITES [focuses] on topics for which no other appropriate competent bodies exist”, which is true. It isn’t only international organisations, like the WTO or the CBD, who can’t do what the CITES can, neither can small private entities.

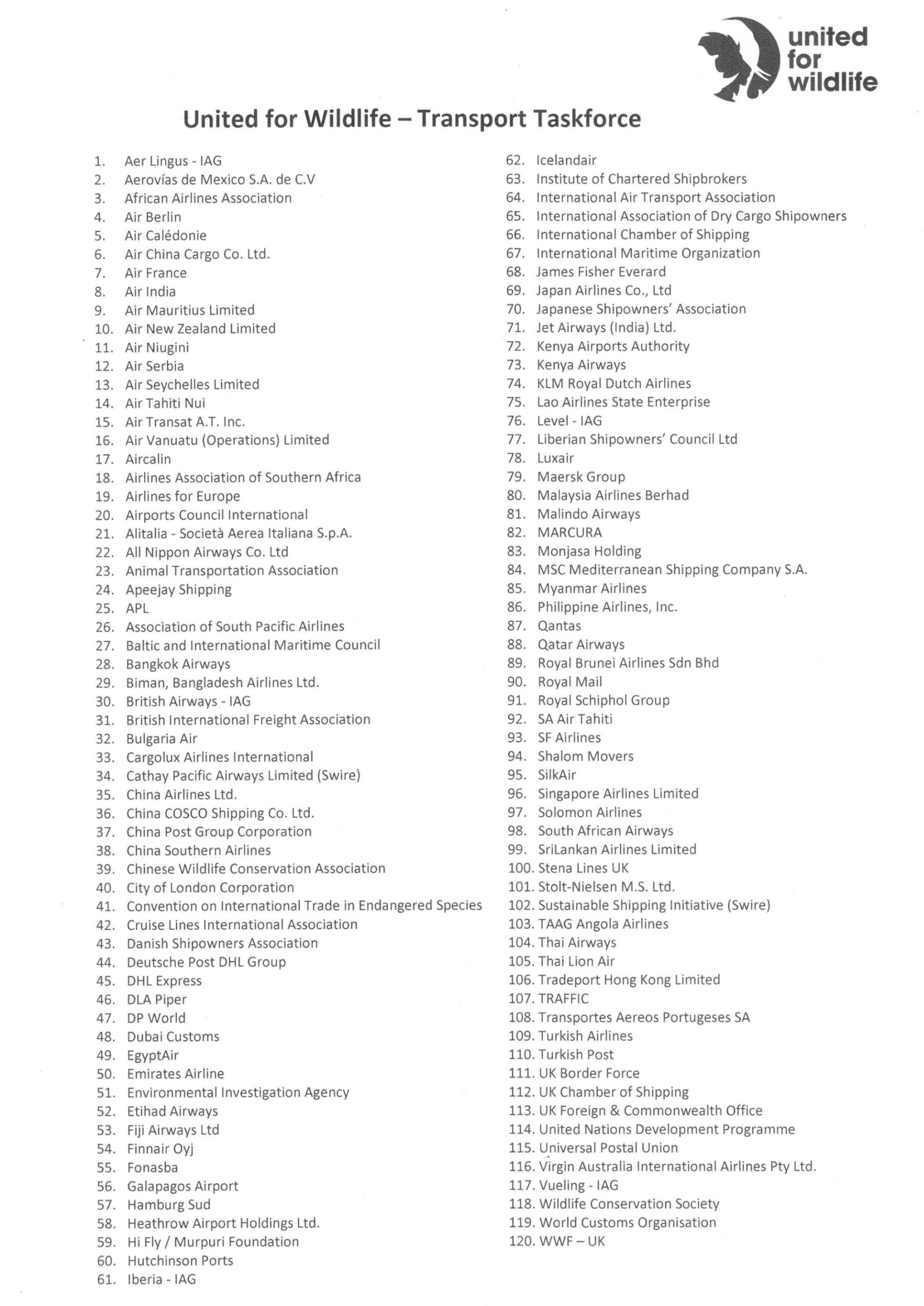

Maybe the reason conservation NGOs and academics feel they have a licence to perpetuate the illusion that the legal trade system is working is because it has been overlooked by key influencers. It is disappointing that Prince William’s conservation charity United for Wildlife, and its chairman, former conservative UK government cabinet minister William Hague, ignore all the problems with the CITES in the work of the Transport Taskforce, whose declaration states, “We, as Members of the Taskforce, will not knowingly facilitate or tolerate the carriage of wildlife products, where trade in those products is contrary to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wildlife Fauna and Flora (CITES)”.

Prior to the global pandemic, Nature Needs More wrote to Prince William, sending a copy of the letter to Hague. In the letter we write, “We wanted to bring these legal loopholes to your attention, as the Transport Taskforce could play a role in influencing CITES and its signatory countries to move to an electronic permit system, which can be integrated with customs; this has been discussed for nearly a decade. While the current, paper-based system remains in place, any work the Transport Taskforce undertakes is limited by this obsolete trade monitoring system and can only scratch the surface of the issue”.

Sadly, there was no response and, to-date, many of the countries covered by the airlines and shipping companies who were a part of this 120-member Taskforce still use the 1970s CITES paper permits, including the UK. Everything in the Transport Taskforce Preamble, from, “timely information” to “enhance[ing] data systems” and “develop[ing] a secure, harmonised system”, ignores the well know problems of CITES trade data – the system that doesn’t know what it doesn’t know.

By ignoring the upgrade the CITES system needs, they closed their eyes to their own declaration, “We will not knowingly facilitate or tolerate…”. And now the likes of United for Wildlife have chosen to back small private entities to monitor the global supply chains for endangered and exotic species.

Given how stuck the conservation sector seems, it came as no surprise to read an article on the RUSI website, Evolve or Perish? Global Action on Illegal Wildlife Trade, stating, “Over a decade, our collective endeavours have driven IWT up policy agendas and established a burgeoning global counter-IWT funding and implementation architecture. Enabling large-scale programming worldwide, such a radical transformation in thinking and action around a single crime has seen few parallels across other illicit markets. Tangible results have been seen for some species, resulting from supply and demand-side action. Yet fundamental challenges remain: 10 years since global signatories first gathered in London, and despite the scale of investment, our collective impact on the overarching threat has been limited”.

This failure was predictable, because any thinking that didn’t involve tackling the problems with the legal trade system was not a “radical transformation in thinking and action”.

So, what is likely to happen now that the CITES leadership have courageously acknowledged that they can’t cope with the workload, given the lack of resources? Instead of genuinely modernising and adequately resourcing the global regulator – “for which no other appropriate competent bodies exist” – most likely is that CITES signatory countries will agree to curtail the workload of the Secretariat and permanent committees by ‘prioritising’ away items.

That reading is of course highly subjective, by focussing on the articles of the convention (which were drafted in the late 1960s), an outdated listing mechanism, and an inability to consider the commercial realities of the massive international trade in wild species, run by giant corporations, will mean that CITES will wither away instead of reforming itself to address the issues that underpin its failure – lack of funding, no direct regulation of business, and the wrong choice of regulatory model (negative listing instead of positive listing).

What has happened here is wrong. The people who made the decision to impoverish the regulator, and those who have fallen into line with this, have created a shocking and shameful legacy; they should be professionally ashamed.

When this global business scandal is finally put under the spotlight, it must be called out for what happened, wild species were the collateral damage to enable corporate and investor greed. Between 1975 and 1981, a system was tested to see if it could corral this greed, by 1981 it was clear it couldn’t.

When global conservation players ignored this, they made the decision to unleash an unchecked monster, with an all profit, no responsibility approach. In doing this, they must take responsibility for all that has been lost to unchecked overexploitation since 1981. The question is, with the CITES courageous plea for support, can these conservation organisations and academics finally tap into the courage they obviously need to help fix the system?