Reading news reports recently, there appears to have been a step up in rhino poaching in South Africa in the last few months

Pro-trade groups are trying to attribute this to ‘poaching syndicates reacting to the threat of a potential legal trade in rhino horn’ (see red box). There is no evidence to back up this statement. This is pure conjecture to support their desire for a legal international trade; in the last few months the domestic trade in rhino horn has been legalised in South Africa, which I have commented on previously.

Equally you could say that this step change in rhino poaching levels in the last few months could be a result of ‘poaching syndicates preparing for the opportunity to launder illegally poached rhino horn into the recently agreed South African legal domestic marketplace’. Before I explore this in more detail, let’s look back at the history of rhino poaching from 1990 onward.

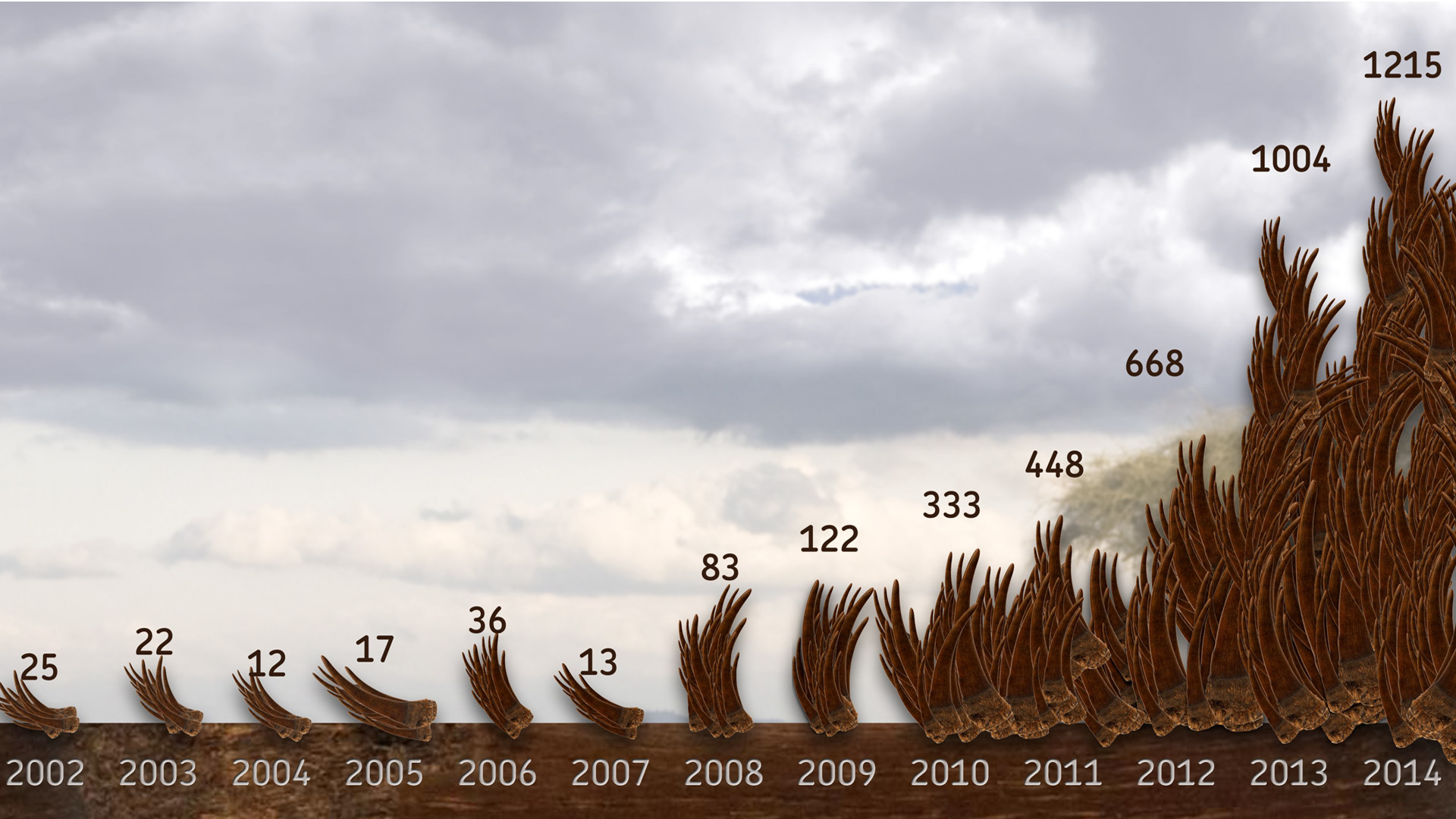

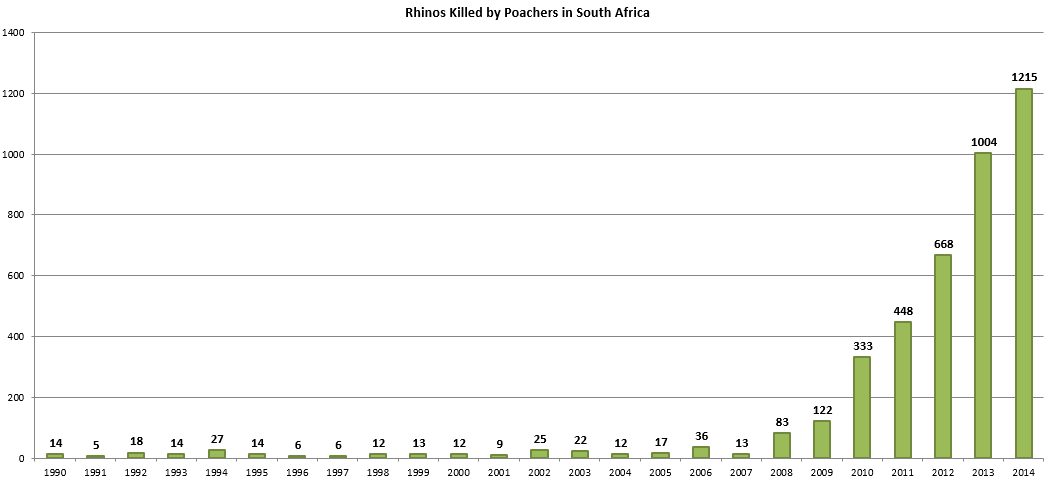

Timeframe 1: 1990 – 2014

After the efforts put in place to tackle the rhino wars of the 70s and 80s, when the Yemen was seen as the primary driver of poaching, there were nearly 20 years of very little poaching activity.

The pro-trade groups choose to ignore this extended period, when rhino populations recovered in range countries including South Africa. The South African records show that from 1990 until 2007 there was minimal rhino poaching activity. The pro-trade people have never ever been pushed to justify their statement that a trade ban hasn’t worked, when it clearly did for nearly 20 years.

So, what happened around 2007? We can’t say for certain, there are some rumours that it was triggered by stories in Viet Nam that rhino horn had cured cancer in a former politician. The politician has never been found or named. In all likelihood, this story was designed and manufactured by traffickers who realised how comparably safe it is to get rich from dealing in wildlife and as such decided to create new markets. Remember the Salesman’s Mantra: “Sales tricks are what you use to sell something to someone who doesn’t even know they want it.”

Andrew Parker, then CEO of Sabi Sand, stated in a 2013 CNN interview “I think they [criminal syndicates] caught us napping, quite honestly, we were caught unprepared”. Which is true, it wasn’t until several years later that efforts to tackle the poaching crisis were significantly ramped up. It took until 2012 to conclude that Viet Nam was the key driver behind the new poaching spree.

Certainly, the term demand reduction has only entered conservation vocabulary in the last few years. This slowness to fully understand the scale of the new rhino poaching crisis meant that by the end of 2014 there were huge concerns that the exponential growth in rhino poaching couldn’t be stopped.

Timeframe 2: 2015 – 2016

While 2015 was still a record year for rhino poaching when you sum up all the range country losses, the rate of rhino poaching in South Africa had slowed. When the official South African figures came in, at the end of 2016, there was another slight reduction. While there is understandable scepticism of the figures reported by the South African government, if you apply an exponential fit to the losses between 2001 and 2014, South Africa was heading toward 2000 rhinos being poached in 2016. Now the government can hide some losses to drought and natural causes, but it would be difficult to hide 1000 rhinos lost to poachers!

So, the exponential rise in poaching has been halted, most likely through a combination of massively increased protection measures, law enforcement and tackling desire on the demand side. It was looking very promising until the South African government caved in to a reversal of its domestic trade ban by the Supreme Court, on purely technical grounds, and decided to legalise the domestic trade instead.

Timeframe 3: March 2017 Onward

What are the implications of creating a legal domestic trade in South Africa and does legalising trade reduce illegal poaching and black-market activity?

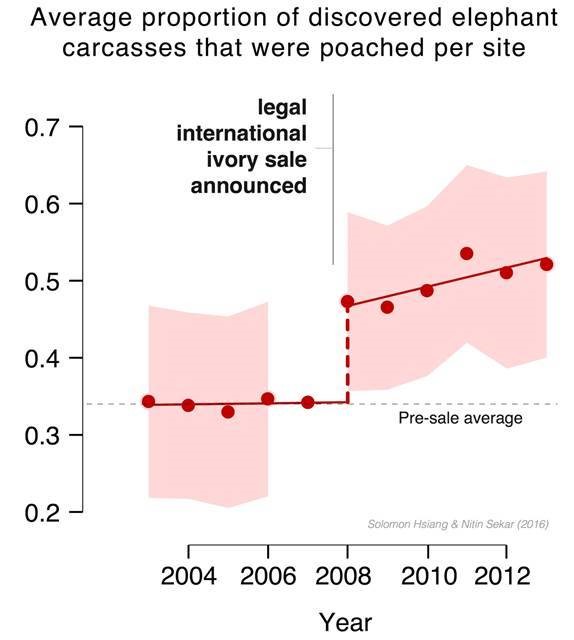

This question was previously asked in relation to the impact of the one-off sales of the ivory stockpile in 2008 on elephant poaching.

As the paper highlights, the monitoring of elephant poaching, pre and post the one-off sale of the ivory stockpile, ‘provided an opportunity to evaluate the first major global legalization experiment in an internationally banned market, where a monitoring system established before the experiment enables us to observe the behaviour of illegal suppliers before and after. International trade of ivory was banned in 1989, with global elephant poaching data collected by field researchers since 2003. A one-time legal sale of ivory stocks in 2008 was designed as an experiment, but its global impact has not been evaluated.’

As the paper highlights, the monitoring of elephant poaching, pre and post the one-off sale of the ivory stockpile, ‘provided an opportunity to evaluate the first major global legalization experiment in an internationally banned market, where a monitoring system established before the experiment enables us to observe the behaviour of illegal suppliers before and after.

International trade of ivory was banned in 1989, with global elephant poaching data collected by field researchers since 2003. A one-time legal sale of ivory stocks in 2008 was designed as an experiment, but its global impact has not been evaluated.’

Evidence from paper would indicate the announcement of legal sales actually triggered an increase in poaching activity.

Before this analysis was published the assumption had been that poaching didn’t increase as a result of the one-off legal sale, but all prior analysis only looked at trends and not the raw data. In reality, there was a clear, statistically significant step change increase (discontinuity) in elephant poaching in 2008 and it fully correlates with the timing (announcement) of the one-off sale. I have highlighted the abstract and would recommend that those interested read the paper’s conclusion.

In hazarding a guess as to why this happened, given the sale was widely published in the lead up, I would say new syndicates would have been formed to take advantage of the opportunity of laundering illegal ivory in to the legal one-off sale.

Once these new syndicates/channels were developed, they simply stayed in business after the sale occurred and weren’t dismantled.

That would be my guess, based on commercial experience, but again this is conjecture, given there is no specific analysis of why this sudden increase in poaching occurred.

Conclusion

We have a clear historical example for a similar illegal wildlife product and illegal market in which the announcement of trade legalisation correlates with a significant increase in poaching.

It can therefore be argued that the currently observed increase in rhino poaching in South Africa is a direct result of the announcement of a legal domestic trade in rhino horn in the country.

Poaching syndicates are NOT reacting to the THREAT of a legal market as implied by the pro-trade lobby. They are reacting to the OPPORTUNITY of a legal market – the opportunity to launder illegal horn through the domestic trade and the ability to export horn for ‘personal purposes’.

Summarising:

- The trade ban worked for nearly 2 decades from 1990 to 2007, though the pro-trade groups like to divert people from this fact.

- Even though there was a delay in establishing range country and demand country strategies to counter the new poaching wave, there is evidence that they slowed the growth in rhino poaching in 2015 and 2016.

- The real question is not why the pro-trade lobby makes spurious arguments in support of their personal enrichment agenda. That is to be expected, but:

a) Why do the large conservation agencies let them get away with making crap arguments and are not countering these arguments on the basis of available data and research? It is not hard to see the flaws in their model

b) Why are the large conservation agencies ALWAYS late to the argument? Why do they ALWAYS allow the pro-traders the first-mover advantage? Can they not comprehend that coming second means having to do double the work in convincing the public? Maybe they need to think about their ideology around requiring definitive, hard data which can stifle significant movement or positive action toward saving these iconic species; and all too often the hard data arrives far too late. The elephant research was published in 2016, eight years after the one-off sale in ivory and the step-change in elephant poaching. The rhino may not survive such a delay. Principle 15 of the 1992 Rio Declaration sets out the Precautionary Approach “where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”