There is a difference between climate scientists and conservation scientists. The vast majority of actively publishing climate scientists – 97% – agree that humans are causing global warming and climate change. Even for those among us who, after decades, challenge the 97% claim, and undertake their own ‘fact check’, they found the consensus is “shared by 90%–100% of publishing climate scientists” in one survey, while another found it to be 84%.

So, let’s say the ‘overwhelming majority’ of climate scientist agree that humans are causing global warming and climate change and as such they challenge the fossil fuel industry.

The biodiversity equivalent to ‘climate scientists and the fossil fuel industry’ is ‘conservation scientists and the industrial extraction of wild species for profit’, known as the ‘sustainable use’ of wild species. But here is where the comparison ends.

The ‘overwhelming majority’ of climate scientist know that fossil fuel extraction is driving climate change, so they lobby to transform the energy industry and our energy needs. When it comes to conservation scientist the overwhelming majority support ‘sustainable’ use. The big problem is that this is an act of faith, conservation scientists are not actively publishing any proof that this extraction is sustainable. This was clarified (again) earlier this year in a new study, The Positive Impact Of Conservation Action.

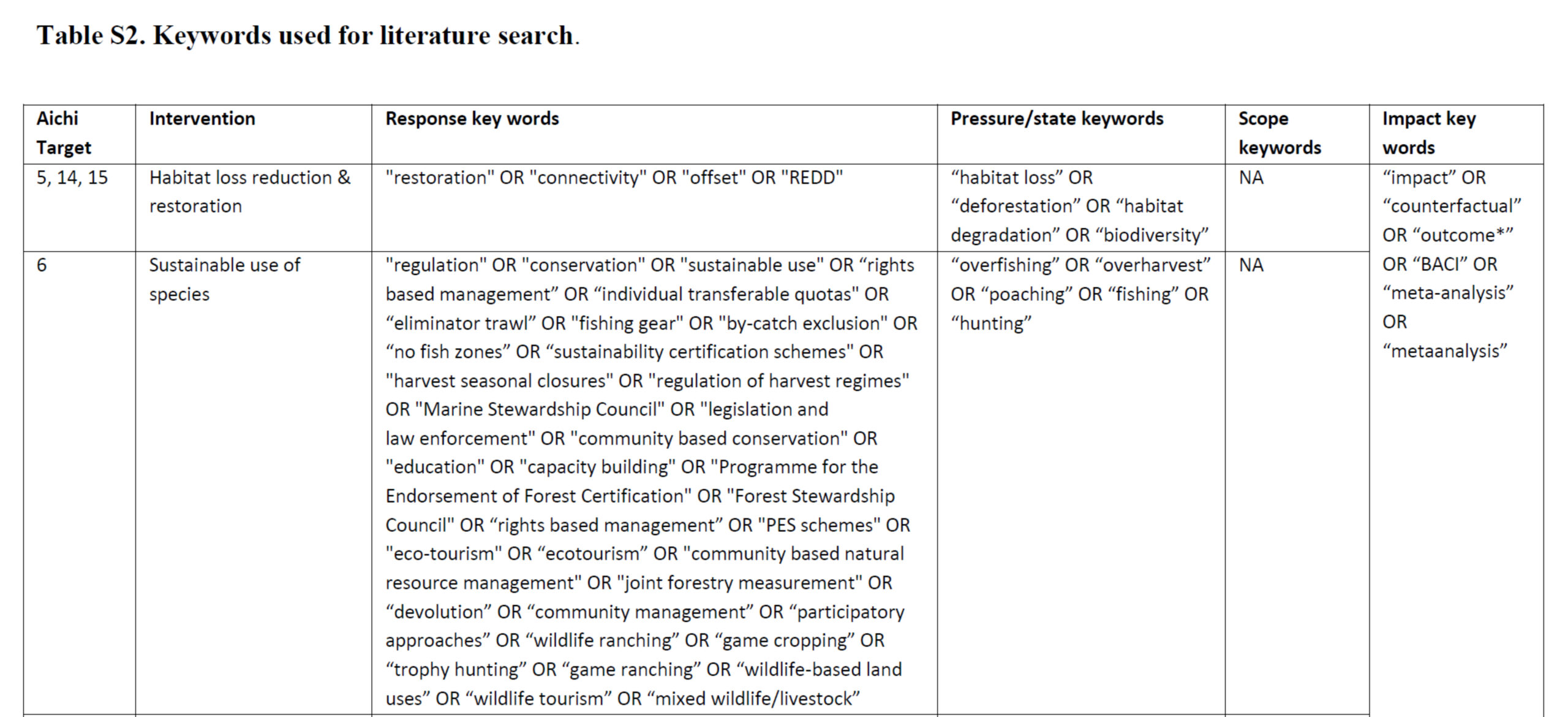

The paper, which had 33 authors, conducted a meta-analysis of scientific studies on the impact of conservation interventions. Starting with a scan of over 30,000 potentially relevant publications, they found 186 studies evaluating the rate-of-change impact of conservation interventions globally over the past century. One type of conservation action they analysed was the sustainable use of species; yet the finding on the impact of sustainable use interventions was ‘inconclusive’. Why?

The major issue was that this meta-analysis could find only 5 publications related to the sustainable use of species that analysed the rate-of-change and a counterfactual to the intervention. This is particularly surprising given several of the authors are big proponents of the sustainable use of wild species. Given how broad the keyword search was in the sustainable use of species category, compared to all the other categories, they tried very hard to find proof, but it simply didn’t exist.

This is not the first meta-analysis to struggle to find any positive (or even neutral) impacts of the sustainable use model. A 2021 publication, (Morton et al.), Impacts Of Wildlife Trade On Terrestrial Biodiversity found a large negative effect of trade on species populations (compared to control populations/sites). They stated, “We examined 1,807 peer-reviewed articles and >200 TRAFFIC reports yet found no support for a quantified, existing sustainable trade”. As with the recently published paper, whilst they had different selection criteria, they had similar problems finding suitable studies to include at all.

To make matters worse, CITES instigated a massive IPBES report, Assessment Report on the Sustainable Use of Wild Species, which analysed over 6,000 studies. Unfortunately for CITES this report found the same problem that Morton et al. pointed out – international trade is linked with overexploitation and the massive growth in international trade has driven the increase in unsustainable use.

In emails with the corresponding author of The Positive Impact Of Conservation Action, regarding any insights as to why only 5 publications related to the sustainable use of species were available for the meta-analysis, the response was:

Looking at our database, we had over 30 [sustainable use] papers drop out because they did not meet one or more of those criteria. The two biggest reasons studies were:

- There were not at least two data points in each of the intervention and counterfactual (or at least 3 datapoints for before-vs-after study designs) that would allow us to calculate a rate of change in the intervention and in the counterfactual. As stated in the paper, we used rate of change to create a standardized variable and effect size that would allow comparison of such a heterogenous set of papers across many categories of intervention and dependent variables.

- Dependent variables did not represent biodiversity at the species, ecosystem or genetic levels which is what we were aiming to measure in terms of conservation impact. For example, they were measuring things like movement of fishing vessels or human community attitudes/behavior.

I do not think it is the case that there are no studies into sustainable use interventions; I just think most studies have not been done in a way that would allow for the evaluation of the impact of conservation efforts on biodiversity over time.

I found this closing statement by the corresponding author of the paper curious. Paraphrasing, “There have been studies of sustainable use interventions, they just have not been done in a way that allows the evaluation of the impact on biodiversity over time.” Curious because the principle of sustainability is all about impact over time, as outlined in the definition by the US EPA.

So why are climate and conservation scientists different? The lack of suitable studies into sustainable use needs to be seen in relation to the centrality of the ‘sustainable use’ mantra within CITES, the IUCN and the CBD. The idea that sustainable use is a valid conservation intervention and ‘works’, is both an implicit and explicit assumption underpinning CITES and the wider conservation world.

Most global conservation organisations support the sustainable use of species model.

Nature Needs More has extensively analysed CITES trade data and papers that use the CITES trade database and other data sources (like UN Comtrade and LEMIS), since 2016. What we found is that there is simply No Evidence that any trade under CITES can be considered sustainable because the data are of such poor quality that nothing can be reconciled. Imports cannot be reconciled with exports or CITES data with customs data or CITES data with LEMIS data etc. Not even for some of the most valuable trades where individual specimen are both tagged and should be easily counted – like crocodile skins or live macaques.

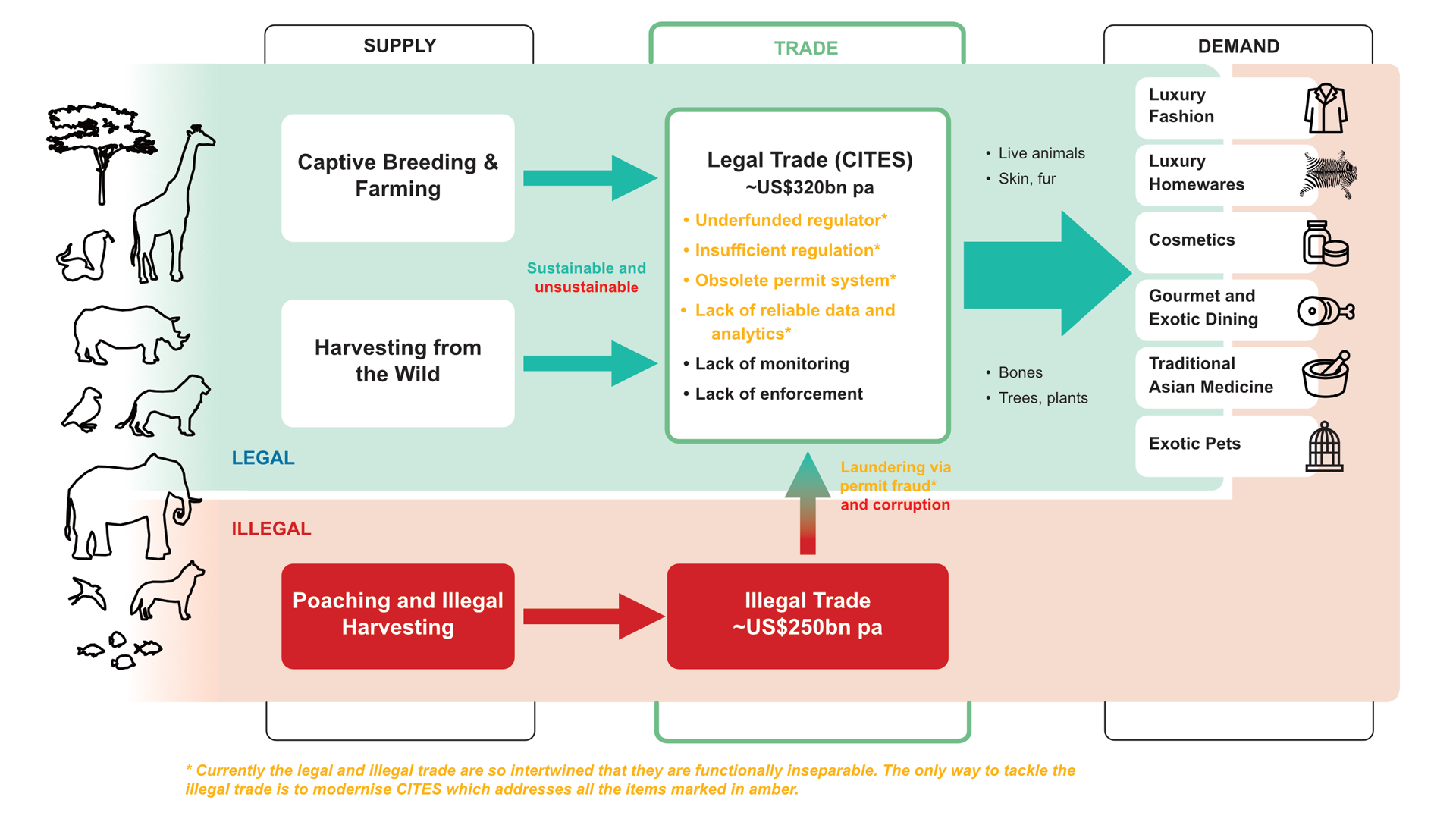

Therefore, it is necessary to ask the question, if the lack of studies into the effect of sustainable use actions is either deliberate or ‘convenient neglect’, as is the lack of comprehensive, consistent and reconcilable trade data. Is the global conservation industry, NGOs and IGOs, enabling companies to maintain plausible deniability on the industrial scale of the of their use of wild species that is driving biodiversity loss? The void created by the lack of quality supply chain data is certainly enabling the overselling of sustainability and greenwashing. The landmark May 2019 IPBES report into the global extinction crisis confirmed that direct exploitation for trade is the most important driver of decline and extinction risk for marine species and the second most important driver for terrestrial and freshwater species. After seafood, fashion and furniture and the biggest users of wild species. The countries profiting the most from this trade are those within Europe, North America, China/Hong Kong and Japan.

No conservation scientist should downplay the fact that this recent meta-analysis couldn’t find more than 5 studies with at least two data points in each of the intervention and counterfactual (or at least 3 datapoints for before-vs-after study designs) that would allow you to calculate a rate of change in the intervention and in the counterfactual. That is really not a high bar for looking at the biodiversity impact of a conservation action.

CITES lists over 40,000 species, with new listings coming spread out over time and with sufficient lead time for new listings/trade quota coming into effect to make it easy to study before/after scenarios. Yet that hasn’t been happening and that ought to be of major concern to anyone involved in the conservation of species traded internationally.

Given how long CITES has been around and how large the international wildlife trade has become over the last 40 years, the lack of studies into the conservation impact of ‘sustainable use’ is a rather damming indictment of conservation science. A 2016 European Parliament Report states. “The wildlife trade is one of the most lucrative trades in the world. The LEGAL trade into the EU alone is worth EUR 100 billion [US$112 billion] annually”. The silence of the conservation industry on the legal trade and the lack of proof its sustainable is deafening.

At least climate scientists have been willing to go where the data leads them and acknowledge that climate change is accelerating and to point out significant gaps in their data and models. Nothing of the sort has happened in conservation science or in CITES.

Thankfully, conservation organisations and academia have been monitoring the decline of species for decades, even if they have been unwilling to link this to trade. This has made it hard for business to use the same disinformation and propaganda they have used to delay climate action. In the case of biodiversity loss, they can’t “reposition biodiversity loss as a theory, not a fact” or pay for advertorials on the “weak” evidence, “nonexistent” proof.

Instead for the last two decades or more luxury industries, including fashion, furniture, beauty, jewellery and wellbeing, have published glossy sustainability reports. In addition, companies and industries have paid for sustainability advertorials and supported the rise of sustainability directors, managers, officers, editors and journalists. All this noise has provided no proof to their statements on the use of wild species as the ‘raw materials’ for their products. Their meaningless sustainability statements have gone unchallenged by corporate conservation and all but a handful of academics. While climate scientist challenged the misinformation published by fossil fuel companies, this same misinformation by the companies who use wild species in their opaque supply chains has flown under the radar.

The 2019 IPBES report confirmed trade was a key driver of biodiversity loss and highlighted 1 million species are at risk of extinction in the near and not too distant future. This didn’t lead to a shift in research on the impacts of trade or ‘sustainable use’. Conservation scientists appear more than happy to carry on with their faith in the sustainable use mantra, probably because they are cognisant of who provides their funding and what these funders believe.

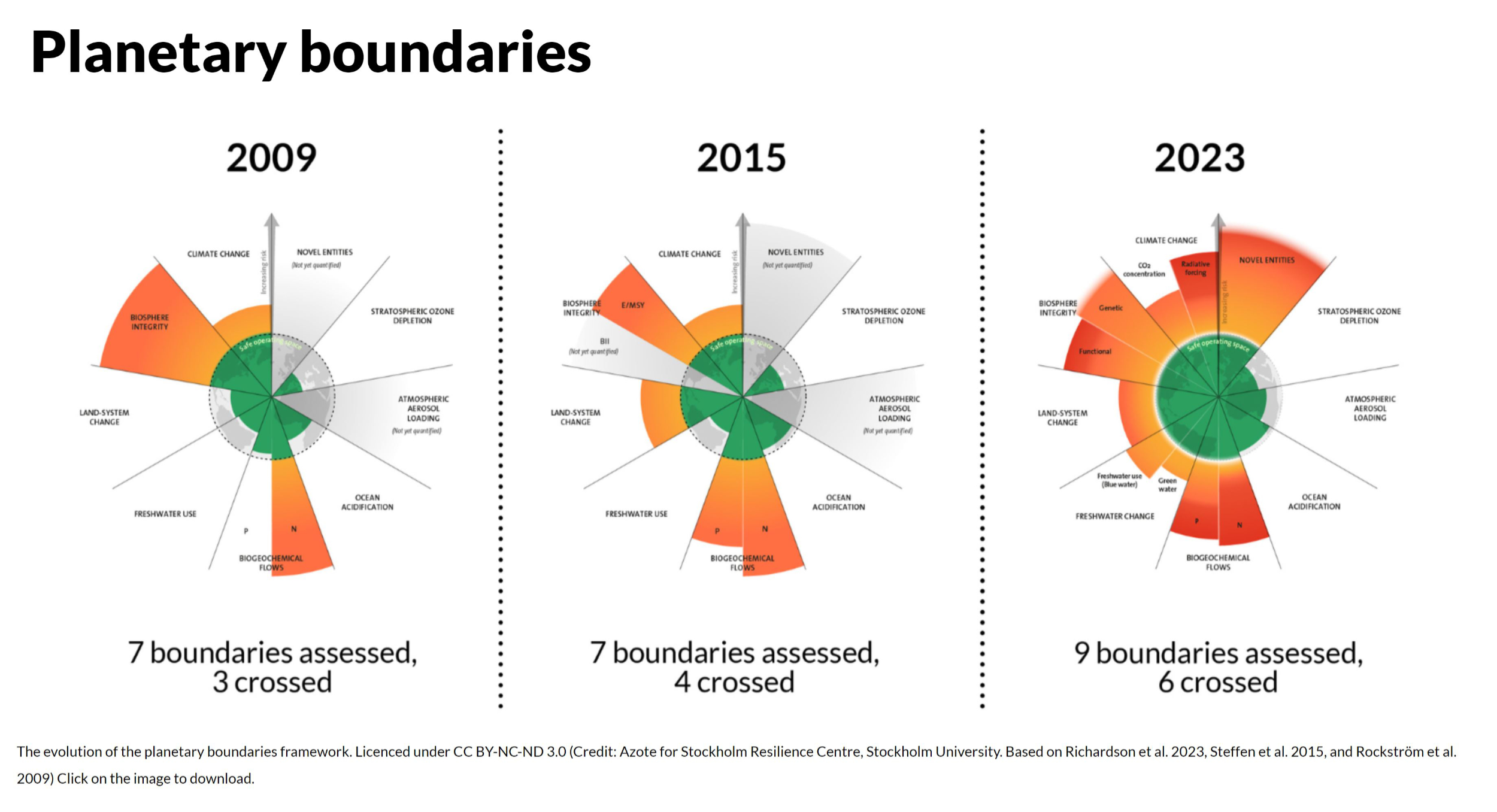

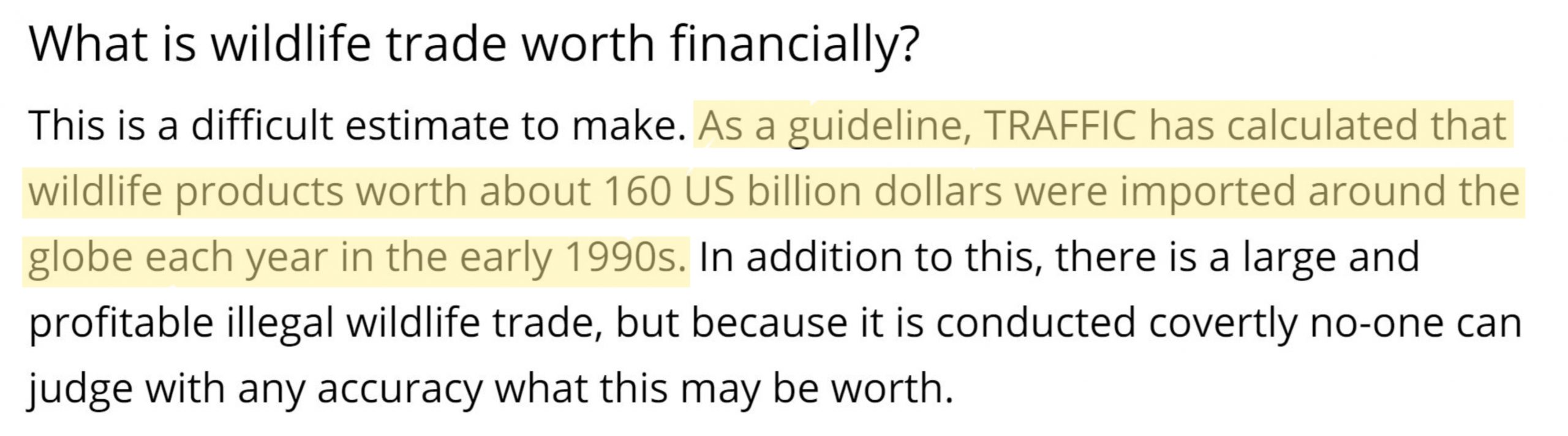

The conservation industry is on borrowed time regarding their avoidance of the legal trade in wild species. While models such as the Planetary Boundaries confirmed the loss of biosphere integrity was already in the in the high-risk zone by 2009, a lack of widespread mainstream media and public interest on this issue has enabled yet another decade of delay on tackling the consequences of the legal trade on biodiversity loss and meant the conservation scientists haven’t needed to ‘speak truth to power’ about this. Just one example of how the legal trade in endangered species has been clinically sidestepped for over 30 years comes from the WWF website. A couple of years ago I asked someone on the WWF leadership team to explain why the WWF’s website, to this day, only quotes a figure of the value of the legal trade from the early 1990s.

How does having information 30 years out-of-date, about the legal trade in endangered species, fulfil WWF’s mantra of an evidence-based approach? Their reply “If you’ve got stats that hold more gravitas pls do send them through”. I can’t agree that there is ANY gravitas in data that is 30 years out-of-date. The self-assured hubris among some global conservation agencies needs a bit of a reality check.

Will capitalists ever voluntarily walk away from “one of the most lucrative trades in the world” unless they are forced to do so? Unlikely! And, if not, who will apply the necessary pressure? Not the conservation industry it seems.

But it isn’t only the conservation industry and scientist who are on borrowed time because of the legal trade in wild species, we all are; biodiversity loss can drive planetary collapse. Which is why Target 5 of the 2030 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework is, “Ensure that the use, harvesting and trade of wild species is sustainable, safe and legal, preventing overexploitation, minimizing impacts on non-target species and ecosystems, and reducing the risk of pathogen spillover, applying the ecosystem approach, while respecting and protecting customary sustainable use by indigenous peoples and local communities”.

As we head to the next round of discussions, at the CDB CoP16 in Columbia later this year, I can 100% state that there is No Chance of achieving Target 5 by 2030. Conservation scientists 50 years of faith in the unproven sustainable use model has made them complicit in this failure.