A recent article in the Daily Maverick put all the same old pro-trade spin on opening the international trade in rhino horn. While there are plenty of counter arguments, again they have also been discussed for more than a decade, again-and-again.

So, with this response, I will only clear up one of the misleading statements. The article implied that multi-millions of dollars has been spend over the last decade on rhino horn demand reduction campaigns and “the demand for rhino horn seems not to respond” to these activities. I have heard and read these statements many times in the media.

Having volunteered my time to work on rhino horn demand reduction strategies, under the banner Breaking The Brand (to stop the demand), from 2013 until the last campaign in late 2018, it is necessary to challenge the misinformation and disinformation about demand reduction.

In a July 2014 article, I asked the question, Should We Legalise Trade OR Focus On Demand Reduction? I asked this question early because you can’t do both, it is an ‘either or’ strategy. Demand reduction can’t decisively work while the commercial opportunity of trade remains on the table because you simply can’t have mixed messages. Some pro-trade supporters were obviously concerned about the increased interest in demand reduction at the time and the implications it had for their pro-international trade agenda.

In a January 2015 I wrote, Poor Quality Demand Reduction Campaigns and Strategies Will Provide Ammunition for Pro-Trade Lobby Groups, highlighting that, “Currently too many awareness raising and education strategies are being packaged and sold to the public as demand reduction and they are not.”, continuing, “In recent months we have seen projects targeting primary and secondary school children in Asia being called demand reduction campaigns. They may, through education, ensure that these children don’t become the next generation of users in 20 years’ time, but they are not demand reduction campaigns.”.

To clarify the difference between awareness-raising, education and demand reduction, I created this model:

To be clear, a good quality demand reduction campaign elicits an emotional response in the current user groups to such a level that it triggers them to stop using rhino horn in a timeframe that is useful to save the rhino from extinction on the wild. The ‘current user groups’, defined in the model, are those who are wealthy enough to afford genuine rhino horn. When I did my initial research, between 2012 and 2014, from the beginning I only found two triggers that would stop genuine buyers using rhino horn:

- If there was a risk to their reputation – if buying rhino triggered reputation/status anxiety

- If there was a risk to their health – if consuming rhino horn triggered health anxiety

That was it, reputation/status anxiety and health anxiety, nothing more. In addition, there was significant evidence that much of the rhino horn on the Vietnamese market was fake. The beliefs and desires of the people who can’t afford genuine rhino horn are completely irrelevant to a well-crafted demand reduction campaign.

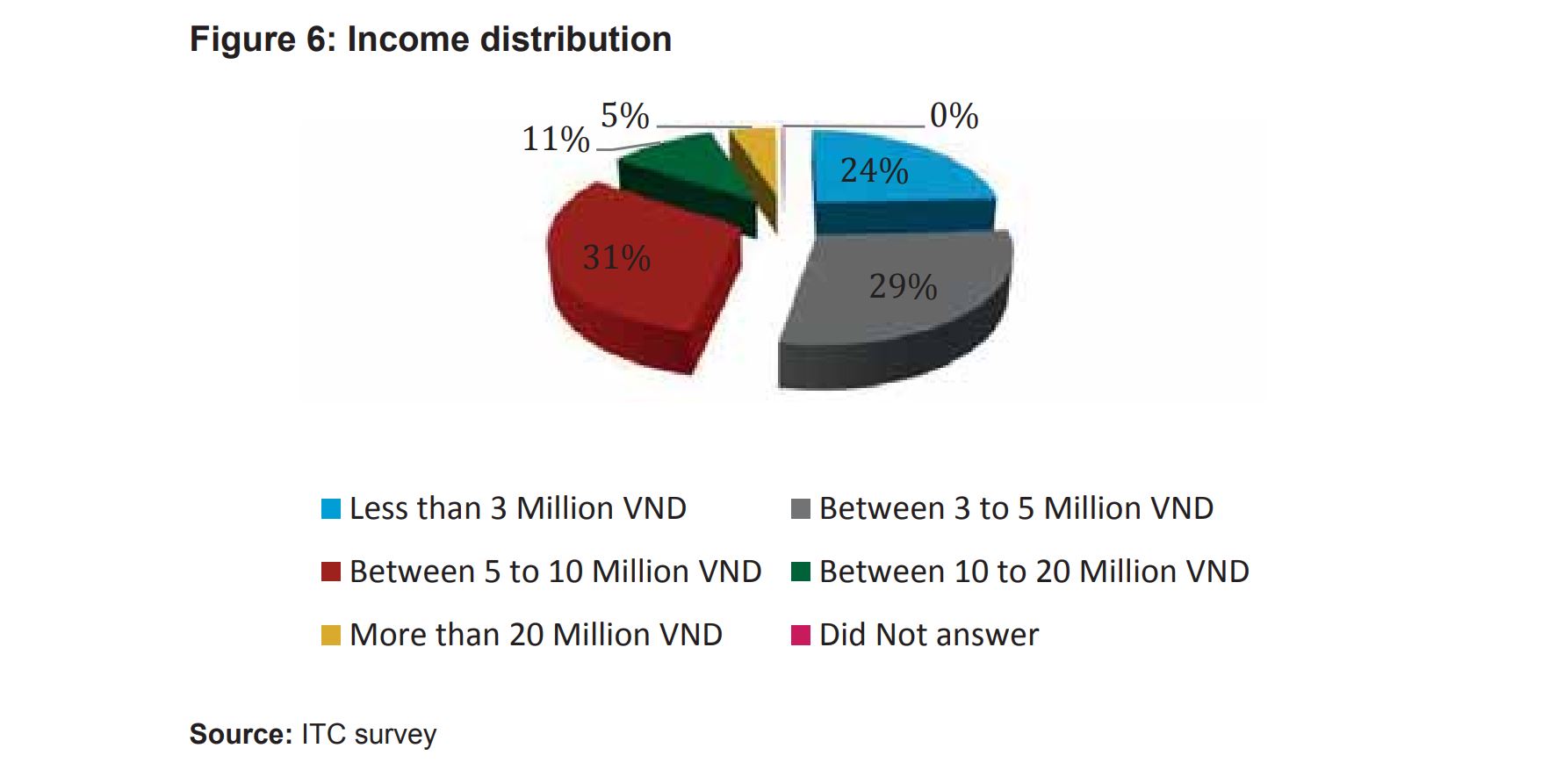

I stress this because over the years there have been several surveys purporting to interview rhino horn users in Viet Nam, where the stated salary of the group surveyed means that they can’t possibly afford genuine rhino horn. Maybe the most shockingly ignorant was a 2017 report published by the Geneva based International Trade Centre, which stated its findings are based on a survey of 1,000 people in Viet Nam. The paper claims (page 54) that the price of illegally poached rhino horn [in Viet Nam at the time of the research] is US$8,400/100g. This needs to be compared to the monthly income of the 1,000 people surveyed (page 12):

The exchange rate at the time meant: 20 Million VND/Month = US$882/Month

All the ITC could honestly say is that some of the 50 people in the top income bracket surveyed MAY have had a sufficiently high disposable income to afford genuine rhino horn. The reality was that the authors didn’t prove they surveyed anyone earning a sufficiently high monthly income to guarantee they were (consistently) buying genuine rhino horn in relevant quantities.

You can’t make decisions on the right strategy based on raw data which isn’t relevant to the debate you are supposedly trying to inform. This is equivalent to LVMH interviewing welfare recipients to determine its future product range.

Just as with this ITC report, I have heard statements from conservation about being fully committed to providing objective, science-based evidence in crafting demand reduction projects. To test this in February 2016 I published How Much Is Spent On Rhino Horn Demand Reduction Campaigns?, filtering the rhino horn campaigns running at the time through the comparative model I had created. In parallel, after reading through reports, websites and articles, I estimated the levels of funding going to awareness raising campaigns, compared to education and finally demand reduction campaigns. In this 2016 article, I also linked to a segment where Pelham Jones, chairman of the Private Rhino Owners Association (PROA) and pro-trade states “Despite billions being spent on an annual basis to collapse the illegal demand, it is not working.” – sound familiar? Despite the billions Jones stated, and now Wiltshire reiterates, in the recent Daily Maverick article, I found no evidence that anything other than pocket change was being spent on ‘genuine’ demand reduction campaigns; and not much has changed since 2016. The conservation sector must take some responsibility for providing the pro-trade groups with this level of ammunition through badly designed demand reduction campaigns or as a result of simply stating that their campaigns were demand reduction when in reality they should have been classified as awareness-raising.

As a result of this finding, in September 2016, I wrote It Is Time For Large Conservation & Donors To Take Demand Reduction Seriously.

While global conservation brands were receiving funds to help educate the broader sector about demand reduction strategies, after doing all this work, many went on to produce the same types of adverts they have done for decades. These adverts do not resonate with the users, but the conservation sector and donors like them; so who are the adverts being produced for? As one anti-smoking campaigner told me, “The tough, confronting campaigns do the grunt work of stopping smoking, the positive/nice to look at campaigns keep the donors happy.”.

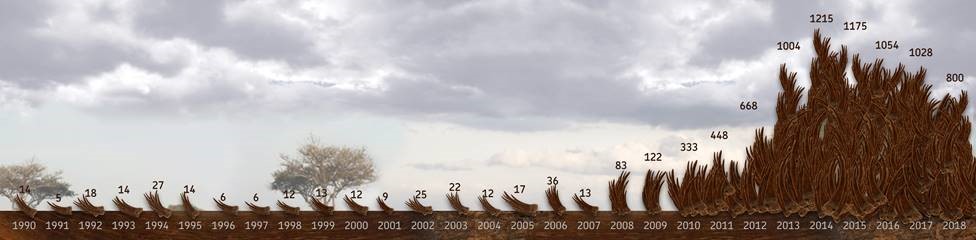

Even with the relatively small amount of funding that went to genuine demand reduction campaigns, there was anecdotal evidence that this was contributing to a reduced desire for rhino horn. Together with security in range countries, campaigns in demand side countries were helping to reduce poaching levels.

Possibly the most insidious misinformation campaign about demand-side countries, by those pushing for trade, is that people in China, and Asia more broadly, can’t change; a frankly ridiculous statements implying that because the Chinese and people of SE Asia have used rhino horn in the past then, obviously, they will ALWAYS use rhino horn.

In case you need an example which clearly demonstrates what happens when a society stops tolerating a behaviour that has been practiced for centuries let’s look at Lotus Feet – the practice of foot binding which is thought to have started in the 10th century. Foot binding became popular as a means of displaying status and was also considered as a symbol of beauty in Chinese culture. Foot binding was outlawed in China over a 100 years ago, following almost a thousand years of the practice; one of the concerns in China was that foot binding may have been seen as a symbol of China’s backwardness.

A decade ago, Jo Farrell, award-winning photographer and cultural anthropologist, tracked down the few remaining women, all in old age, and photographed them for her book Living History: Bound Feet Women of China.

It is insulting for the pro-rhino-horn-trade group to say the people of China and SE Asia can’t change their behaviour. If we applied the same ‘people can’t change’ principle to South Africa then the country would still have an Apartheid Government, Nelson Mandela would have died in jail and there would be no ‘born free’ generations.

How behaviours become entrenched and also how they change is based on just three things. Which behaviours are rewarded, which are punished, and which are tolerated. What is tolerated is the most insidious.

Once society stopped tolerating foot binding it was stopped. Once society stops tolerating the commercialisation of wildlife and the natural world, we might have a chance to save the little that is left. Over a decade of watching the rhino horn pro-trade/no-trade stalemate and the poverty of discussion surrounding it, I’m not holding my breath that we can change our relationship with nature in time to save ourselves. If we can’t do it for the wildlife icons – the rhinos, elephants, tigers, lions, sharks – what chance have the reptiles, amphibians and the million species at risk of extinction as highlighted in the 2019 IPBES report?

What has become very clear is that people don’t understand the difference between a crisis and a collapse. Ecosystem collapse is caused by the wealthy countries’ over-consumption of the natural world and that means we need to reduce demand. To be a true demand reduction campaign, that means targeting the primary users (those wealthy enough to afford luxury fashion, furniture, seafood, pets etc.) and doing it in a timeframe that saves us all from extinction.