In August 2017, Nature Needs More facilitated our first Conservation Lab. We were delighted to be able to contribute to a project being driven by Donalea Patman, Founder of For the Love of Wildlife, in her work to close the Australian domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn.

Little did we know at the time that this would start Nature Needs More investigating the lack of transparency and monitoring in the legal trade of animals and their body parts. It appears that it is not only the illegal trade that is huge problem, but also the lack of proper regulation, traceability, transparency and enforcement in the legal trade in wildlife creates no end of problems for threatened or endangered species.

For CITES (or any) system to be relevant in preventing illegal trade, the legal trade monitoring system needs to be completely transparent and provide the ability to track individual items from origin to destination, without any loopholes, gaps or opportunities to launder illegal items into the legal trade system or marketplace. This is evidently not the case, and it is not restricted to ‘poor’ countries.

Re-Cap: Australian Test Case

In Australia, a very rich country, the lack of investment committed to fulfil its CITES signatory obligations was laid bare as a result of For the Love of Wildlife’s #NoDomesticTrade project. To explain, let’s consider one example: Analysis of trade in Elephantidae specimens between Australia and UK from 2010 to 2016 using the CITES Trade Database. At the most recent date of exporting data from the CITES database on 30 May 2018:

- The number of Elephantidae ‘specimens’ exported from the UK to Australia amounted to 2,953 ‘units’

- In the same timeframe the number of Elephantidae ‘specimens’ recorded as imported in to Australia from the UK equalled 3 ‘units’

- A discrepancy of 2,950 ‘units’.

How are we supposed to reconcile and monitor trade with such flawed data? Any permit system that is this useless is counterproductive – it creates the illusion of traceability and control, whilst in reality offering nothing.

In addition, the Australian domestic market is completely unregulated and once items have entered into the country they can be traded freely without any restrictions. The government is relying on self-regulation and ethical behaviour of the local antiques industry. Undercover filming by Donalea Patman and FLOW volunteers, undertaken at businesses in nearly every state and territory, captured video evidence of the unethical practices in the antiques market in relation to ivory, including footage of retailers advising customers on how to take the items out of the country illegally (click in images to see the video in full).

|

|

Submissions to the Australian Joint Parliamentary Committee on Law Enforcement on policing the trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn demonstrated that there was no real way of knowing the true scale of the legal trade in Australia or the extent that illegal items were laundered in to the local marketplace. So, what happens when you scale this up to look at the legal trade in wildlife and their body parts on a global level?

Global Trade

First, as a reminder, CITES has had over 40 years, as the key agency and facilitator of trade in fauna and flora, to evolve and perfect a system critical to conserving wildlife. Instead the system appears antiquated, not transparent, not consistent and not fit for purpose. Similarly, there is little evidence the signatories to CITES have been willing to invest in improving the system over this extended timeframe, despite the current industrial-scale poaching crisis. It seems like CITES is suffocating, and as a result ineffective, under the scale of the legal trade.

The legal trade in wildlife is worth US$320Billion per annum and currently 35,000 species of both flora and fauna are listed for either exclusion from trade or trade restrictions. Given the scale of the trade that needs monitoring and its financial value the annual budget to CITES to administer the global trade system is a paltry US$6Million.

Let me just summarise that for clarity:

- Value of legal trade is US$320Billion per annum

- Number of species listed for monitoring (either exclusion from trade or trade restrictions) is approximatly 35,000

- Annual budget for CITES Administration is US$6Million

While I am no fan of CITES and I would much prefer a conservation body rather than a trade body to be the key facilitator for our wildlife, if we have to have it this way then we need a massive and well targeted investment to overcome the deficiencies of this antiquated system.

Equally, as I wrote in a blog: A Message To The Australian Antiques & Auction House Industry if the Australian antiques/auction house industry wants to maintain a partial domestic trade in ivory and rhino horn and the Australian Federal Government enables this, then the antiques industry should agree to pay for the monitoring, policing and prosecution costs associated with keeping the trade open. These costs are incurred solely for their benefit. In scaling this up, then shouldn’t any business that wants to trade in animals or their body parts pay a levy to a central body that uses the funds raised to monitor both the legal and illegal trade? This levy should be paid at each stage of the supply chain. We cannot expect to privatise all the profits from the trade without raising sufficient revenue for an effective monitoring and control mechanism. The current situation simply enables trade but fails almost completely when it comes to enforcing trade restrictions imposed by CITES.

In addition to the limited funds to administer the CITES monitoring system, the permit system is still largely paper-based, with an e-permits being discussed since 2010 but with little progress. With CITES lacking the funds to help poorer countries implement such a system this means that most of the exporting countries still use a paper-based system which does not integrate with customs systems, and hence makes traceability and auditing impossible, particularly given the volume of trade.

We know the total legal trade in wildlife is worth US$320billion per annum, which is a mindboggling scale. In order to illustrate what this looks like in practice, it is worth looking at the example of just once species and its value to the legal marketplace.

Just One Product: Python Skin

The harvesting of wild pythons has been ongoing for more than eight decades.

The harvesting of wild pythons has been ongoing for more than eight decades.

As a 2013 article in The Ecologist: What Price That Snakeskin Handbag? states:“The European fashion industry accounts for 96% of the python skin market, with the main importers being Italy, France and Spain. The leading manufacturers and retailers of python skins are the designer brands Hermes, Gucci and Prada….It is a highly profitable trade, with the value of the python skin market estimated to be over £625 million (US$1 billion).”

At CITES 16th Conference of the Parties (CoP16; Bangkok 2013), concerns were raised by several CITES signatory countries regarding the conservation impacts of trade on wild snake populations and the need for greater monitoring and transparency: Traceability Systems for a Sustainable international trade in South-East Asian Python Skins.

In November 2013 the Python Conservation Partnership was established; a collaboration between Kering, the International Trade Centre (ITC) and the Boa and Python Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The objective of the collaboration is to improve sustainability of the python skin trade, conduct research and make recommendations to improve sustainability and transparency amongst other things. In 2014 it published a report Assessment of Python Breeding Farms Supplying the International High-end Leather Industry

While the report concludes that commercial farming of pythons for their skins appears to be biologically and economically feasible, it acknowledges that absence of strong regulatory measures, monitoring and enforcement means captive breeding farms for pythons can be used to launder illegally collected or traded animals and skins; giving examples such as:

Despite large exports of python skins from Lao PDR with a CITES source code C [captively bred], this study found no evidence that python farming is currently taking place [in the country].”, and

“Python skin exports using a CITES source code “C” from countries other than China, Thailand and Viet Nam (e.g., Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos PDR and Malaysia) should be treated with caution until improved data on farms, management and monitoring systems are in place to verify captive production capacities.

There is certainly reason for concern about the scale of illegal poaching of pythons. In 2016, Chinese authorities recovered a massive haul of 68,000 smuggled python skins worth $48 million and was described as the “largest-ever python skin smuggling case.”

It is maybe as a result of monitoring and the potential for laundering that in 2017 Kering announced it was setting up a python farm in Thailand. In a 2017 Guardian article Kering states its farm would begin producing adult skins in 2018, with provision of “a significant number” expected by 2020. [Though] Kering said it did not expect to stop sourcing skins from the wild under the convention on international trade in endangered species (CITES) scheme.

Given the scale of the apparent inadequacies in the CITES trade permit system already discussed and the lack of traceability of individual skins from the source, this means from a fashion industry viewpoint we must then question the use of the CITES framework as a way to justify harvesting snakes from the wild and a way to monitor trade in python skins. This is exactly the same situation as questioning the use of the CITES framework used by antique retailers to justify the continued trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn.

In summary, the lack of transparency highlighted, for just one animal body part, python skin

- 96% of python skins are used in the European fashion market

- In 2013 the value of the python skin market was estimated to be over US$1 billion

- Whole countries have been found to be exporting pythons with a CITES source code C [captively bred] when there is no evidence that python farming is currently taking place anywhere in the country

- This has enabled large scale laundering of illegal python skins in to the legal marketplace, just one seizure of illegal python skins in China in 2016 having an estimated worth of US$48 Million

- Oh yes, and the annual budget to CITES to administer this monitoring system for not just 1 species, but all 35,000 is US$6Million

But this example is just for one product, what happens when you scale these problems up to the global fashion industry?

Just One Industry: Luxury Retail

Before we explore the mechanism the luxury retail industry has in place to transparently monitor its use of animal body parts, lets first look at the total value of the industry:

- In 2016 worldwide luxury retail sales was valued at US$1.25Trillion

- The personal luxury goods market valued at US$289Billion.

- This equated to a market growth of 191% between 1995 and 2016

The last decade has seen an exponential rise in the dialogue and activity regarding sustainable fashion, which has included the luxury end of retail. This has led to a growing movement of sustainably focused consumers and new business opportunities. At the same time there is still too little clarity around the definition of sustainable and this lack of transparency is at best leaving customers confused and, in some instances, has enabled businesses to ‘greenwash’ their merchandise.

Collaborations and frameworks are evolving to bring clarity to this rapidly evolving sustainable fashion agenda. One such collaboration is the Global Fashion Agenda which was founded in 2016. One of the Global Fashion Agenda’s strategic partners is the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, founded in 2009, which has developed the Higg Index, defined on its website as: The Higg Index is a suite of tools that enables brands, retailers, and facilities of all sizes — at every stage in their sustainability journey — to accurately measure and score a company or product’s sustainability performance.

So what evidence is there that wildlife is being factored in to the sustainable fashion strategy to ensure that any legal trade for the luxury or sustainable fashion market does not allow for the laundering of animal body parts from an illegally poached wild cohort?

Publications arising from the Global Fashion Agenda collaboration include the Pulse of the Fashion Industry Report. In the 2017 report, the word ‘wildlife’ features only once and in the 2018 report the word ‘wildlife’ is not mentioned at all.

Publications arising from the Global Fashion Agenda collaboration include the Pulse of the Fashion Industry Report. In the 2017 report, the word ‘wildlife’ features only once and in the 2018 report the word ‘wildlife’ is not mentioned at all.

A second publication is the recently launched CEO Agenda 2018 which discusses the opportunity and need for change. It highlights 1. That there is only a small group of “sustainability champions”, accounting for only 3% of the total market in terms of value and 2. A worrying level of inertia, with a significant percentage of the industry having not taken action on sustainability at all.

The CEO Agenda 2018 highlights 3 core priorities for immediate change, the first being Supply Chain Traceability, which is where the legal supply chain of wildlife products should also sit and, in doing so, integrate with the CITES permit system. But given the long-standing issues with CITES permits as already mentioned, can and is this happening?

In addition to industry and product specific solutions, there needs to be investment in CITES work on e-permits and integration with customs systems, which would close most of the current glaring loopholes in the wildlife trade and supply chains. These are not changes that can be brought about by one industry or industry sector on their own. While there are a couple of wildlife NGOs who are members of the Sustainable Apparel Association, none are directly responsible for monitoring the legal and illegal wildlife trade.

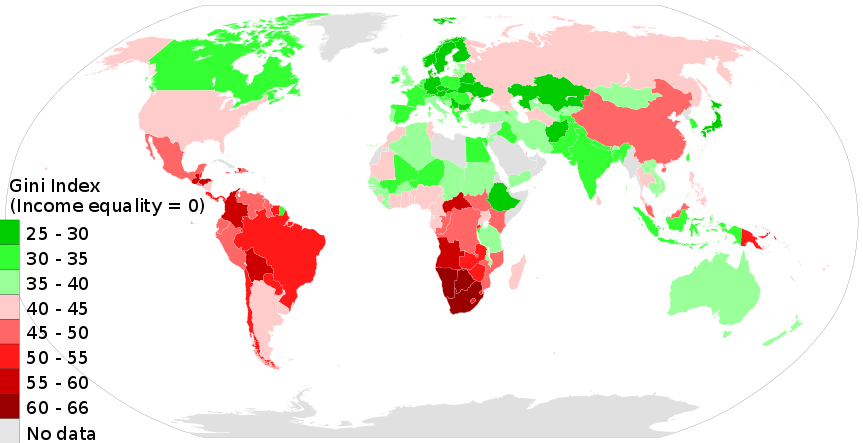

All this considered, at some point we will have to tackle the dominant global mindset and system that has enabled this situation to be reached. A report by Oxfam highlights that the wealthiest 42 people in the world own the same amount as the bottom half of the world’s population, 3,500,000,000 people; 42 people compared to 3.5 billion! After decades of seeing free-trade as the panacea and tax-minimisations techniques, for companies and wealthy individuals, being over generalised as a benefit to all (raising all boats), we are left with a denuded natural world and increasingly unequal societies, as shown by the Gini Coefficient.

Given all this, can we turn the corner and rebuild a transparent, more equal and sustainable system for everyone, not only humans?

The Dominant Economic System

Given how neoliberal, financialised capitalism has taken over in the last 40 years, we shouldn’t be surprised that there has been such a lack of investment in transparency. It stems from the top, with companies and individuals being able to legally hide their earning and wealth.

A string of scandals in recent times, triggered by the likes of the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers, is thankfully leading to greater scrutiny of the systems that have been legally created to facilitate what many see as injustice and inequality. I was invited to speak recently at a conference highlighting the need for change. In the audience were people working in areas of domestic and family violence, the refugee crisis, the epidemic of bullying in schools, chronic health pandemics, including mental health issues. When I put up my last slide, stating something I genuinely believe, a couple of hundred heads nodded in unison. In speaking to people during the break, they had applied this sentiment to their own cause and it resonated.

A recent article in The Guardian may offer some hope: UK tax avoiders face being blocked from honours list The article states “Tax avoiders are being shunned for knighthoods and other honours as authorities clamp down on rewarding people with “poor tax behaviour”.

Well good, it’s a start. But society and nature needs more.