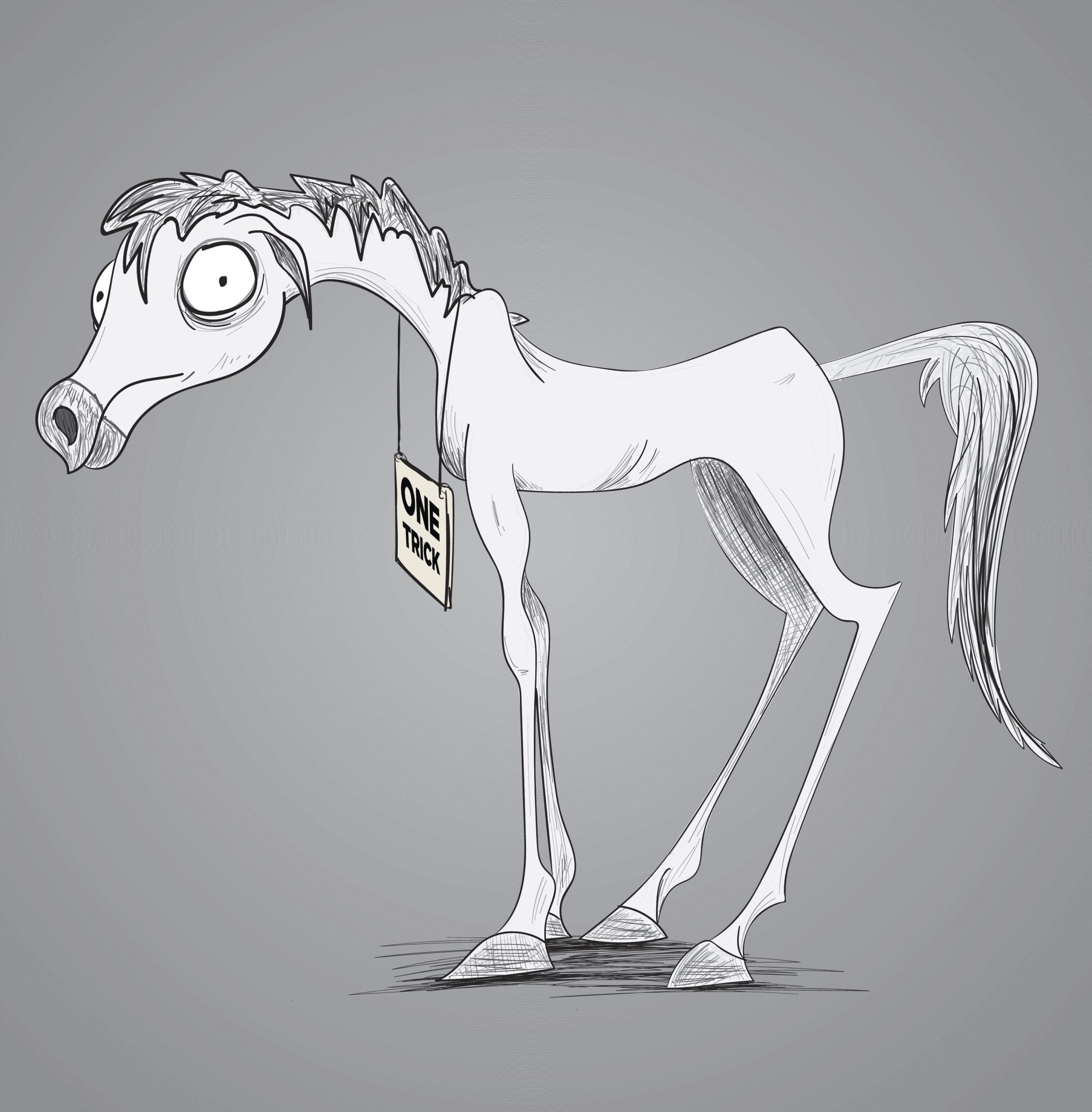

Why one trick pony? Because crocodile farming, in Australia, is the go-to example pro sustainable-use organisations spout to ‘validate’ the sustainable-use model. In articles, at conferences (including CITES CoP18) and in workshops it is the only example regurgitated as the justification of the ideology.

And why do I use the word ideology? Because, as I wrote in a September 2019, after attending CITES CoP18, there is no proof the sustainable-use theory works in practice as there is no useful or reliable trade analytics from 44 years of CITES operation. Sustainable-use is an ideology, not a proven strategy.

In late 2019, work undertaken by world-leading experts in trade analytics confirmed that the CITES trade database is badly designed and an impenetrable data source. The team analysing the CITES trade data agreed that a first step to fixing the problem was for an electronic permit system to be adopted by all Parties.

Given this lack of ‘real’ proof the legal trade can be sustainable, the fallback is to market the success of crocodile farming in Australia; but sustainable-use is just a convenient story that does not withstand scrutiny. CITES lists nearly 36,000 species for trade restrictions, the sustainable-use model cannot be claimed to be valid based solely on the evidence of 1 very wealthy country (Australia) and 2 wildlife populations – freshwater and saltwater crocodiles – farmed in the country.

If CITES, the IUCN and others want to begin to prove that the sustainable-use model is more than an ideology and genuinely valid, they need a lot more evidence. So why not pick the top 50 CITES listed species, by trade value, and provide a decade’s worth of transparent and verifiable trade analytics for each of the 50 species. Surely 50 out of 36,000 is not a big ask! My guess is they couldn’t do this, given the 1970s paper-based system CITES uses, so they rely on just one example and hope they are never questioned. Hence my reference to a One-Trick Pony.

And just to prove the point, an article published on 1 April in response to COVID-19 and the resulting calls for the permanent closing of the wildlife trade, tries to convince us that sustainable-use of a wild species may still be the best way to save them. The example given – yes, you have guessed it – Australian crocodile farming. The author, Dilys Roe, is the chair of the IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group (SULi). It seems even the IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group don’t want to take up the challenge of using any CITES listed species, other than the Australian Crocodile, to validate the sustainable-use model they are supposedly specialists in!

In the article, other than Australian crocodile farming everything else fell into the catch-all statement: “Many other sustainable use schemes have helped conserve species and habitat and support the livelihoods of local people.” But without any data or information to prove the assertion.

CITES, IUCN and any conservation organisation who believes sustainable-use plays a role in reducing biodiversity loss and saving wild species, have reached a point where it is imperative that they decisively prove this theory; particularly given the current work being done to inform the post-2020 global biodiversity framework by parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

Roe’s article states:

“Sustainable use is one of the three key objectives of the CBD,

alongside conservation and equitable benefit-sharing.”

And goes on to explain this, again using the Australian crocodile farming example:

In response [to declining numbers of crocodiles], a new scheme

sought to make crocodiles valuable to local people. It encouraged

them to sell eggs found on their land to newly-created crocodile

farms for rearing and subsequent leather production. Today,

these local people are earning over US$500,000 a year from

the programme

Since there is a dollar figure mentioned, let’s interrogate this in relation to the objective of ‘equitable benefit-sharing’.

Whist researching the value of the global trade in wildlife to the luxury sector, crocodile skin was one species examined. AgriFutures Australia states that Australia accounts for 60% of the global trade in crocodile skins. The main export market for skins are France, Italy, Japan and Singapore. Both LVMH and Hermès own crocodile farms in Australia. (As an interesting aside, the main export markets for crocodile meat are Japan, Malaysia, the USA, Canada and New Zealand).

So, how can we do a back of an envelope calculation to give an insight into this ‘equitable benefit sharing’? Roe’s article has provided the dollar value to local people for collecting eggs from the wild to sell to the farms, namely $500,000 annually. We know from an Ernst & Young report from 2017 that the total values of the crocodile skin trade to Australia is about $150 million, so the ‘equitable benefit sharing’ for local communities, from egg collecting, amounts to 0.33%. Does that seem very equitable to you?

What about the contribution to regulation and monitoring? The Australian Department of The Environment generates about 3,000 CITES export permits each year. As an example, let’s just look at just one 2017 export permit for saltwater crocodile skins exported from Australia to Singapore:

one export permit was for 16,767 units of Crocodylus porosus (saltwater crocodile)

Price of premium crocodile skin is US$9/cm (from 2003 report AgriFutures Australia website), making a 1.5m skin is worth US$1,350 and:

A single shipment of 16,000 skins could be worth US$10-20m depending on size and quality of the skins.

Compared to the value of the shipment:

In summarising then, the ‘equitable benefit-sharing’ amounts to:

| Value of Trade: | Worth about $150 million annually |

| Benefit to the Local Community: |

The annual earnings of local communities for harvesting crocodile eggs for farms amounts to 0.33% of the estimated value of the annual trade |

| Funds Generated by/for Regulation/Monitoring: | Then when you look at money for regulation and monitoring, then the industry contribution can be as low as 0.00044% of the value of the shipment. |

Business and industries are making effectively no contribution to monitoring the trade and this is why Australia may have good laws on paper, but there are no resources to enact them to protect Australian wildlife. This situation has gone on for decades, unquestioned by corporate conservation. I’m not quite seeing the equitable benefit-sharing conservation talks about, even in the example that sustainable-use advocates constantly hold up as the poster child of sustainable-use.

In concluding, I must point to the fact that Roe’s article uses one of the patronising patterns many corporate conservation agencies use when responding to people concerns; stating: “that efforts to reduce the loss of wild species by advocating for their use is counter-intuitive for some people.”

In response, I have to say, I find it counter-intuitive that people employed in these agencies/specialist groups appear to have no understanding of the business and commercial nature of the trade in endangered species. The article points to this lack of critical knowledge when it states: “that to understand sustainable use they need to “ensure there is sound knowledge of the species’ biology and its ecological function”. It does not mention that to complete the understanding there must also be sound knowledge of supply, demand and (legal and illegal) trade data and their impact on the actual (not theoretical) sustainability of the ‘use’.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has shown clearly that the poorly regulated and basically unmonitored legal wildlife trade poses danger to humans and not just to animals. In response IUCN SULi yet again wheeled out the same old one-trick pony, Australian crocodile farms, to ‘prove’ everything is fine and we should go back to ‘normal’, i.e. sticking our collective heads in the sand while wildlife is traded into extinction.

If we rather want to see decisive change and protect ourselves from future zoonotic diseases, then the wildlife trade needs to at a minimum be modernised to be transparent. The latter starts with using electronic permits, traceability from source to destination, industry contributing to the cost of regulation and monitoring and ends with fully incorporating the Precautionary Principle into CITES by moving to a whitelisting model for trade (like we use for pharmaceuticals).

To those who want the legal trade to continue: make it transparent, manage it effectively and decisively prove it works for the natural world and not only for poverty alleviation.