Demand Reduction: A Comparative Difference To Education And Awareness-Raising

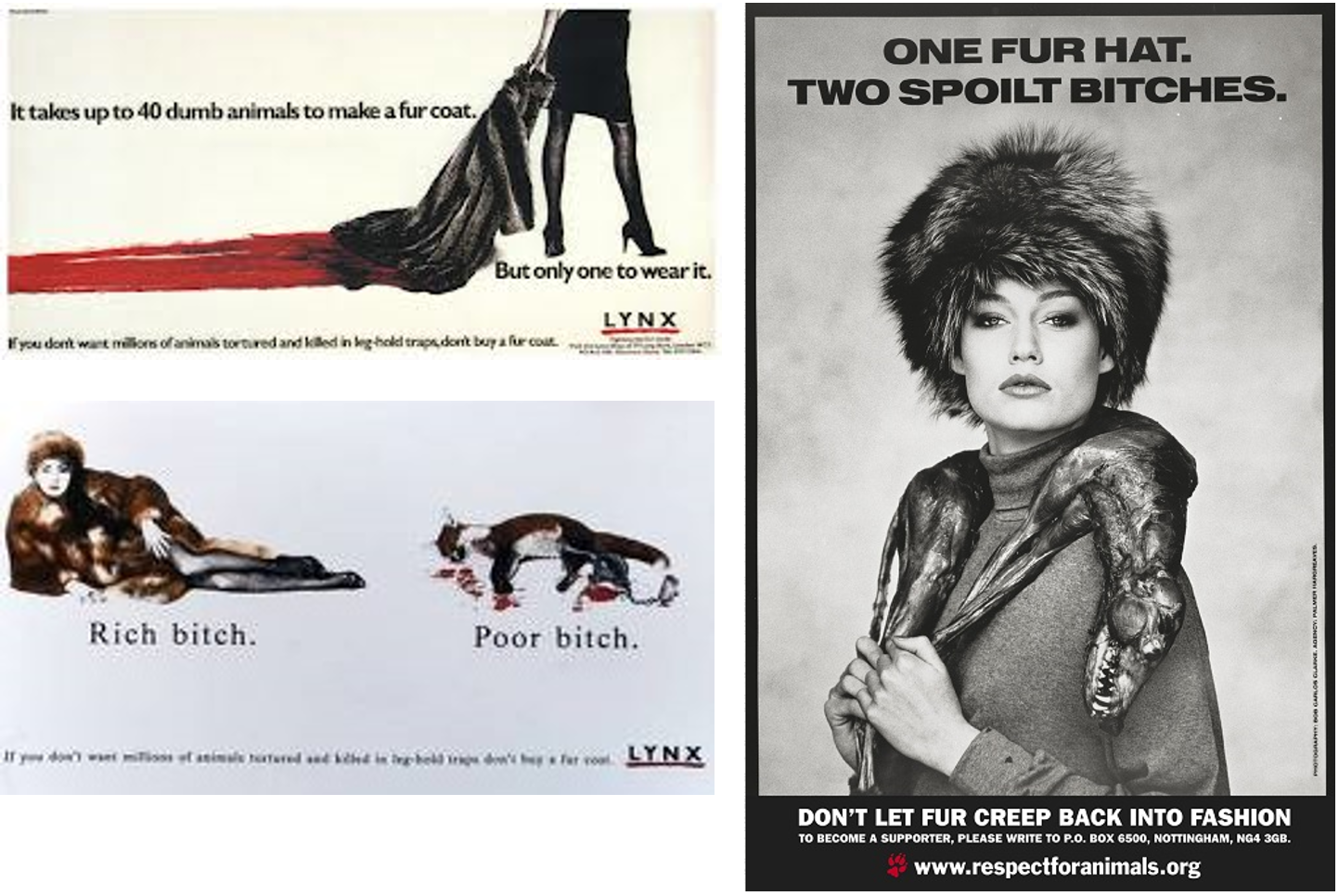

Over the years there have been examples of demand reduction campaigns that have changed consumer purchasing decisions and behaviour very quickly. The most broadly recognisable are the anti-smoking campaigns. These graphic campaigns were mostly run on health anxiety, once the link between smoking and cancer had been firmly established both scientifically and in the public’s mind. From a wildlife conservation perspective, maybe the best known is the 1980s Lynx (now Respect for Animals) ‘Dumb Animal’ anti-fur billboard and cinema advertising campaign. These campaigns also used graphic images, but they were based on status anxiety, not health anxiety.

Key to their effectiveness is that they focus on the actual user of the product, the ‘rich bitch’, not the animal. The consequences for the animal are mostly implied by the use of blood in the ads. They thus conflated a supposedly desirable social status good, the fur coat, with an undesirable social identity, that of a murderer.

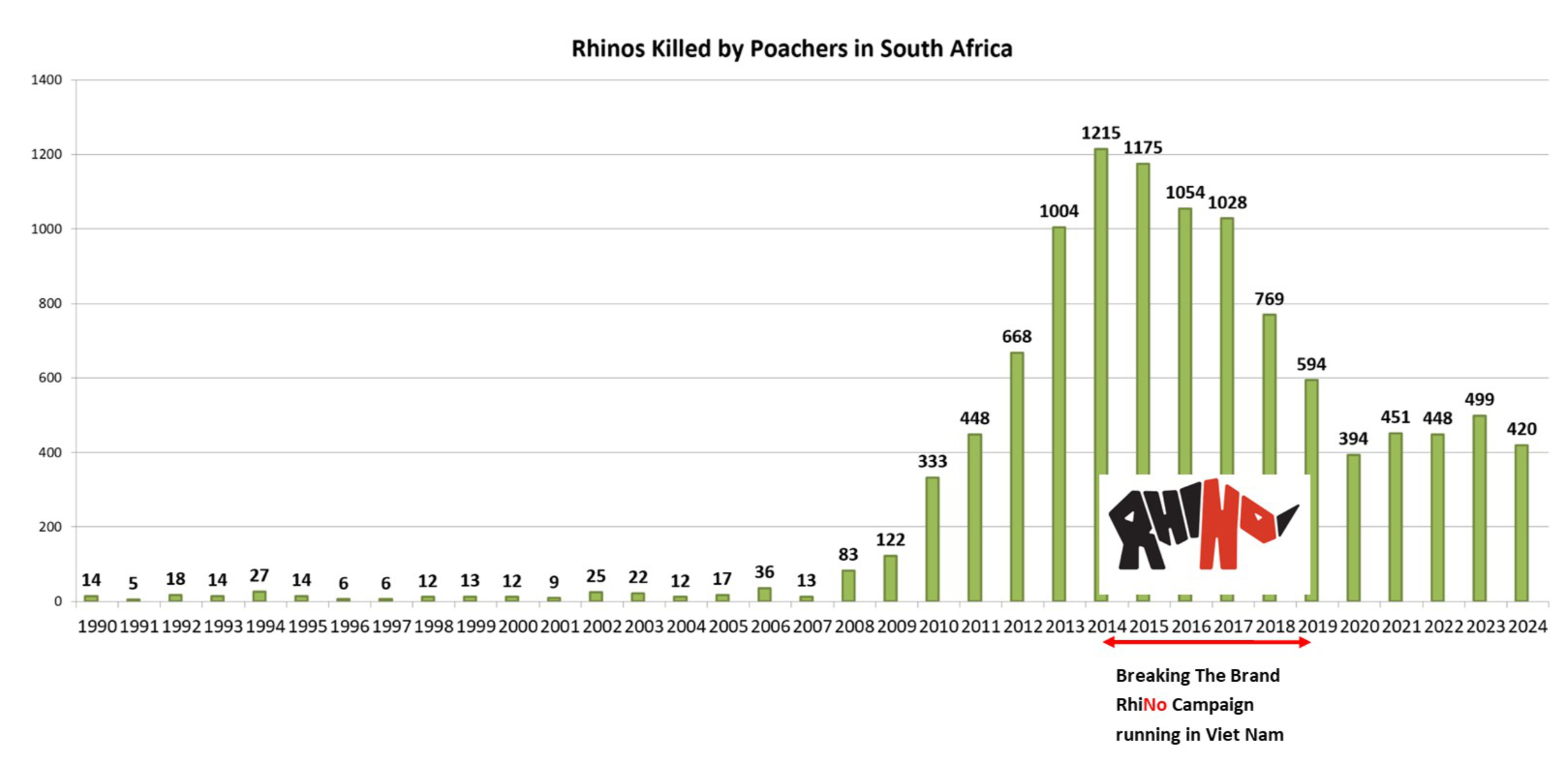

At the start of our Breaking The Brand (to stop the demand for rhino horn) demand reduction campaigns in 2012, key was to understand why Lynx’s ‘Dumb Animal’ campaign, which was acknowledged as being highly successful, has been so rarely copied by the conservation sector. We developed the simple model in the image below to show the difference between awareness raising, education and demand reduction campaigns.

Large conservation organisations run fantastic awareness raising campaigns and good quality education campaigns but largely avoided demand reduction.

Even now, more than a decade later, too many awareness raising and education campaigns are simply being re-badged and sold to the public (and donors) as demand reduction, and they are not.

As early as January 2015 we warned the conservation sector that poor quality demand reduction campaigns would provide the pro-trade lobby with ‘evidence’ that demand reduction strategies haven’t worked to save the rhino, something pro-trade groups have certainly used in the intervening years.

Distinct from awareness raising and education campaigns, what the Lynx campaign showed was that knowing and undermining the identity of the target group triggers emotions that can change purchasing behaviour. This has been known by the advertising industry and marketing departments of companies for over a century. Luxury companies have perfected it to drive up the desire for unnecessary goods and services.

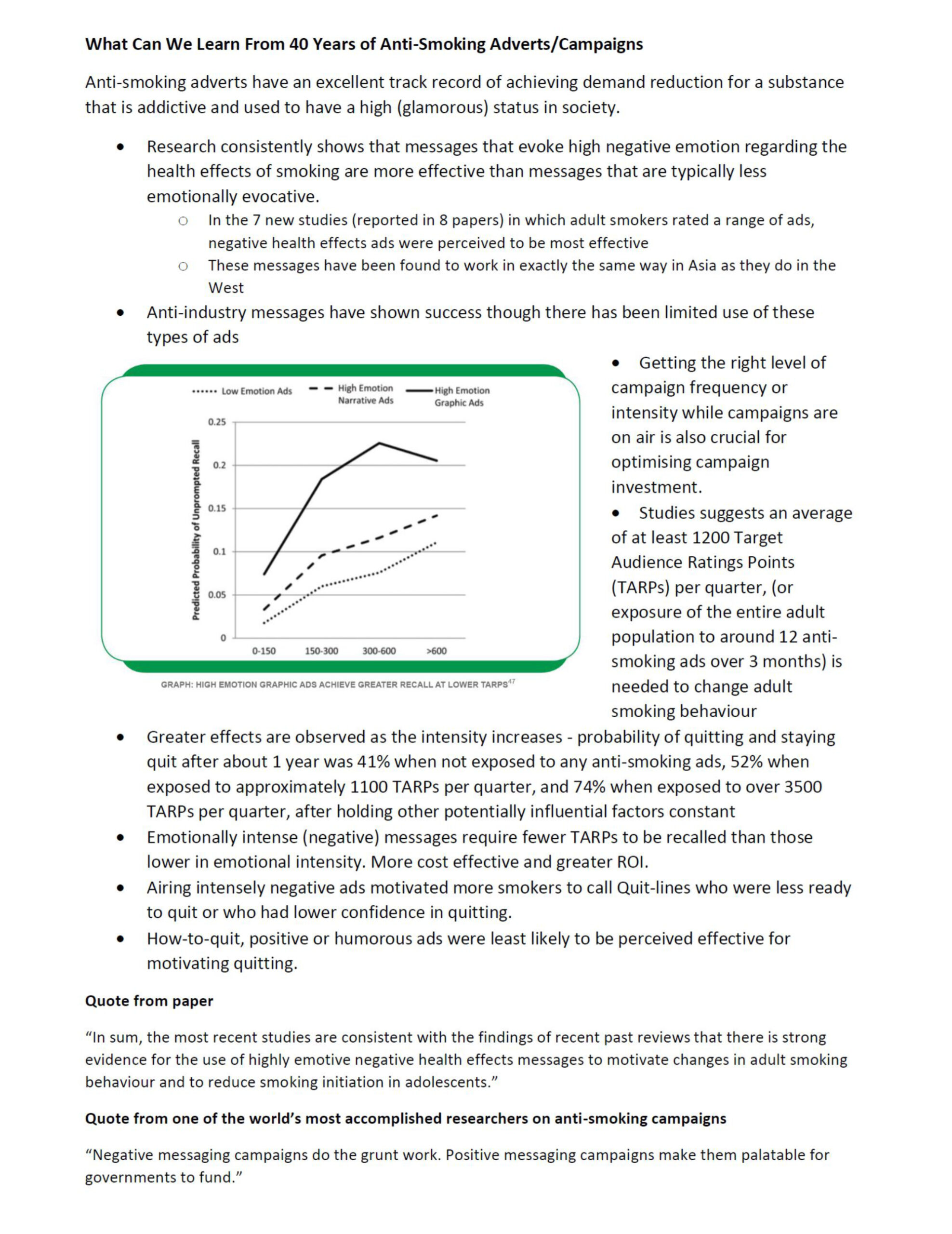

The anti-smoking, drink-driving and workplace safety campaigns perfected this in the other direction, to stop the target group undertaking risky behaviour.

In the early stages of Breaking the Brand, interviewing one of the world’s most accomplished behaviour change experts, from the anti-smoking field, they stated, “Negative messaging campaigns do the grunt work. Positive messaging campaigns make them palatable for (government) donors to fund”.

As a starting point, a good insight into how to create a demand reduction campaign can be found in second episode of the 2014 BBC 2 ‘The Men who Made Us Spend’ program.

But, it is also important to acknowledge that demand reduction campaigns have limitations.

Limitation 1: Individual Action v. Government Action

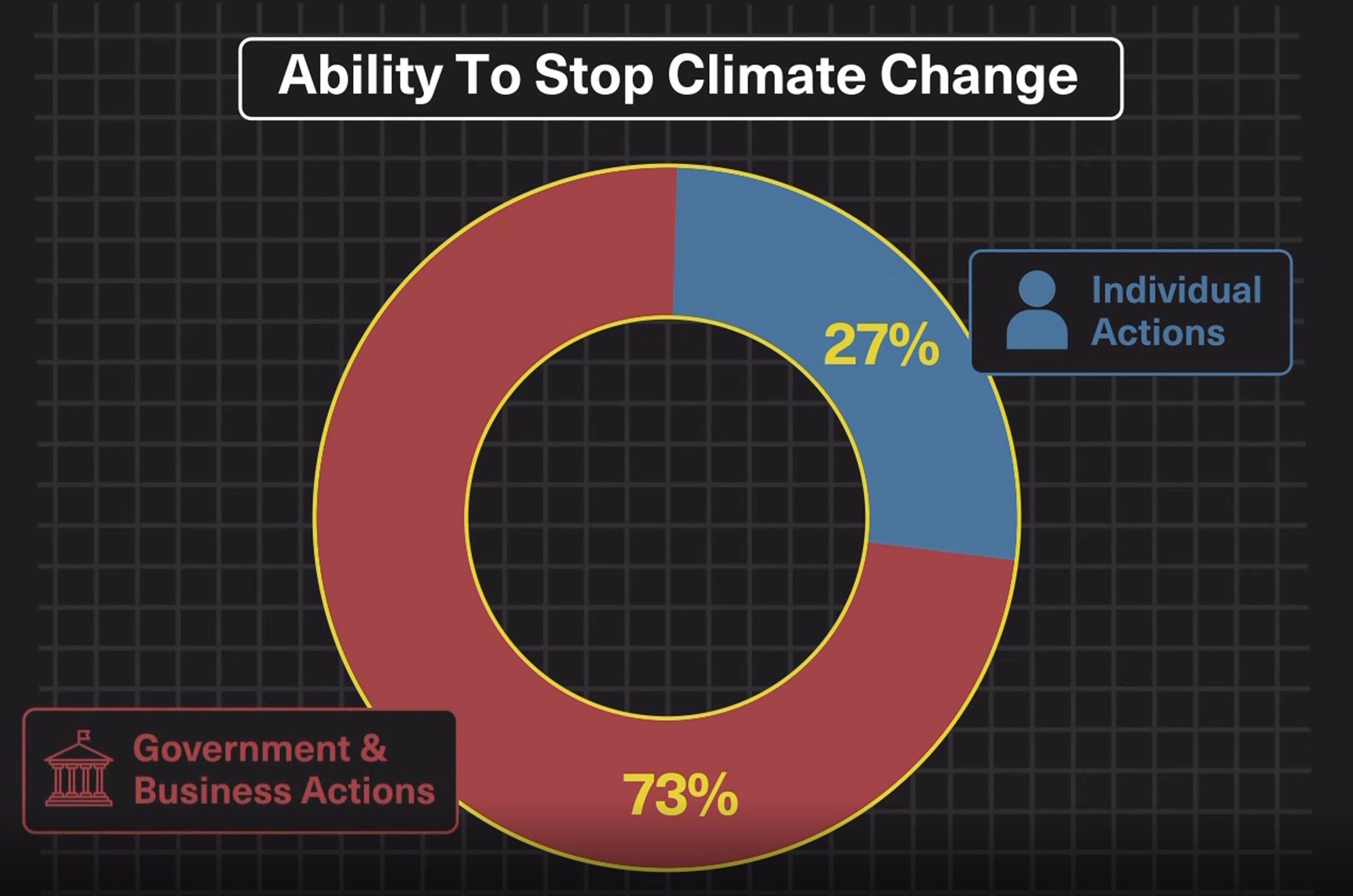

While consumer demand reduction campaigns are needed, it is critical to be clear about what they can and can’t achieve. For climate change, this was well covered in Channel 4’s, 2023 series, The Great Climate Fight.

The research presented clarified that the collective action of individuals could amount to 27% of what is needed to overcome the current trajectory. In the end, government mandated regulation and legislation are required to tackle the climate crisis.

Since the 1980s, when governments worldwide started to dismantle regulators, one of the strategies used to make people believe that this was OK was to say that individual consumer choice could keep business in check and also drive any change needed. This is frankly ridiculous.

Individual purchasing actions (from changing light bulbs to installing rooftop solar) can only take us part of the way. Mandated government regulations and legislation are needed to drive real change. Why?

We have irrefutable evidence that most investors want share price growth and profit growth at all costs. To ensure that executive management plays along with their desire to put profit and stock price above other considerations, such as protecting the environment, they have linked executive remuneration to profit and stock price performance with the primary vehicle being executive stock options.

By making both executive salaries and stock options hugely attractive to the managers most driven by greed and status, they set a process in motion that resulted in shareholder primacy.

We have been sold the mantra that as consumers we have a choice, and indeed we do. But too much of the responsibility of ethical purchasing has been dumped on the individual consumer. Consumers should not be required to attempt due diligence while at the same time the budgets of regulators are cut, and the corporate governance bar is set incredibly low. Even if customers are prepared to do due diligence, this is an almost impossible task, given the lack of transparency of supply chains.

Individual consumer action can only do so much in a system where mandated, government regulation (and legislation) has been minimised and left to voluntary industry self-regulation, voluntary company self-regulation and voluntary executive self-regulation.

A 30-year plus debate of shareholder capitalism vs. stakeholder capitalism has changed nothing. Shareholders won and will keep winning in the absence of mandated and enforced government regulation. But, growing public awareness of biodiversity loss means businesses are also aware that they need to do something – anything – to prepare for when their years of greenwashing are going to be challenged. This is the point we are at, with the creation of a plethora of phantom solutions (offsets, credits, certifications, ESGs etc) to avoid the scale of government intervention needed to properly regulate the business of biomass extraction.

Demand reduction campaigns to reduce the individual’s desire to consume can’t compete with the funding available to drive up the desire to supply for profit.

Limitation 2: The Desire to Supply (For Profit)

The funding for a demand reduction campaign is pocket change when compared with the budgets of companies who invest to drive up desire (lobbying, marketing, advertising, product placement etc).

Luxury companies command marketing and advertising budgets in the billions. A 2020 report published by Badvertising, acknowledged that while “many industries have been recognised as directly and indirectly causing ecological degradation, so far the advertising industry has largely escaped accountability”. Yet we seem no closer to seeing PR and advertising firms being willing to end their relationships with their luxury industry clients.

On the contrary, global advertising spend continues to rise and is projected to reach over US$1 TRILLION dollars by 2026! The luxury industry is one of the major advertisers; on average, they divert 8% of their turnover into funding advertising initiatives.

Of course, the push to increase consumption extends beyond advertising and marketing. It is inherent to much of the social media and entertainment industries. Hence counting advertising dollars alone does not reflect the true scale of ‘content creation’ to boost consumption

Business also wields influence over the ads that their ‘media partners’ will actually publish. There is no way to guarantee that a publisher or social media company will run demand reduction ads that directly target the products or brand of their biggest advertisers. Again, the fact that all media are privately owned limits the potential for even running demand reduction campaigns, or even articles on the legal trade in wild species.

For example, the major expense of the Breaking The Brand (to stop the demand for rhino horn) campaigns came with the decision to pay commercial rates for the adverts to ensure that they were in the part of the magazine or newspaper that was read.

Accepting pro-bono advertising will put an ad in a location that gets low readership or foot traffic. Paying commercial rates didn’t stop some magazines from refusing to run the Breaking The Brand campaign adverts.

Even with the option of running demand reduction campaigns in the media, they cannot compete with industry advertising to drive up demand.

The best evidence for this comes from tobacco advertising. In February 2022, Swiss citizens agreed to modify the Swiss Constitution to ban tobacco advertising reaching children and adolescents. Statistics showed that in:

- In 2022, 23.3% of Switzerland’s population (aged 15 and older) used tobacco.

- Compare this to Australia, where advertisements for tobacco products were prohibited in 1973.

- The 2022-23 National Drug Strategy Household Survey in Australia found the smoking rate among adults (aged 18 and over) was 11.1% and the daily smoking rate was 8.8%.

The public health messages to the smoking population in both countries would have been similar. No doubt both countries would have used the decades of in-depth industry research into campaign frequency and intensity – Target Audience Ratings Points (TARPs) – needed to change adult smoking behaviour. Breaking The Brand’s campaign frequency was calculated using this research to achieve the best ROI, given the limited funds we had available.

The significant difference in smoking rates between Switzerland and Australia show the variation in what result can be achieved when the tobacco industry is prohibited from pushing the opposite messages.

This means that demand reduction campaigns may not be sustainable in the face of industry (pro-trade) push back.

Well researched and designed demand reduction campaigns have the potential to trigger behaviour change in consumers and drive down their desire to purchase rare species. But the demand reduction strategy cannot succeed without an equally important sister campaign aimed at driving down the desire to supply. And, where supply is legal, modern and well funded regulators must be in place to monitor, manage and curb commercial exploitation.

Limitation 3: Mixed Messages Maintain the Status Quo (sometimes for decades)

Mixed messages can take many forms and all result in creating inertia. While mixed messages in advertising (such as with tobacco) may be the most obvious, there are numerous ways to slow behaviour change. Industries have learnt to play the long game, for example:

Normalizing and desensitizing key groups: Fur industry’s strategy to nudge designers and consumers back to fur. A National Geographic article reported that, “At the height of the anti-fur movement, fur auction houses started fighting back, by inviting young designers and design students to “flirt with the material early in their careers” said Julie Maria Iversen, of Kopenhagen Fur. The goal was to make fur just another fine fabric. This investment in nudging and desensitising emerging designers worked. “These young designers have helped take the younger consumer on what Iversen calls “the fur journey…..We start with the young consumer buying a fur key ring, then maybe a little later she has more money for a fur bag,” she said. “Eventually she buys a full coat.” It’s “all part of the agenda, to inspire the upcoming generation of women.”

Undermining the science: Done so effectively by the fossil fuels industry. A good summary of this strategy is outlined in the linked Guardian article, The forgotten oil ads that told us climate change was nothing, with adverts starting a early as the 1980s, touting climate denial messages.

Slowing regulatory change: While again you could point to the tobacco and fossil fuel industries, they aren’t alone in this. Take the example of the asbestos industry. When the UK government was looking at developing new asbestos industry legislation in 1969, they invited representatives of the industry to be a part of the discussions. As the BBC investigation Killer Dust highlights, an internal memo at the time indicated that they believed, if they showed a token effort at compliance, “it is conceivable that we can ‘ward off the evil day’ when asbestos can not be economically applied”. It worked, asbestos products were still been sold decades later. In fact women with asbestos-related mesothelioma are in the process of suing big beauty brands claiming that talc-based makeups are the cause of their cancer. A 2024 article outlines, “In 1924, Nellie Kershaw – a Lancashire textile worker – was the first person to have asbestos cited as a cause of death on her death certificate. How can it be that, 100 years on, asbestos has penetrated into our bathrooms and bedrooms?”, the writer continues, “All the lawyers, doctors and people with mesothelioma I talked to want to see cosmetic talc banned; we need a mass national or international campaign to make this happen. In the meantime, we’ll have to learn to scan cosmetics labels in the way many of us now do with food labels.”

The World Health Organisation states, “There is no safe level of exposure to asbestos that can protect you from developing an asbestos-related disease”; this has been known for decades. Yet it is still up to the consumer to “scan the cosmetics label” to manage the risk.

This example again confirms that it is critical to be clear what demand reduction campaigns can and can’t achieve, and know why the market cannot solve major environmental challenges, when in fact only government regulation and legislation can create the needed change.

In the conservation world nowhere is level of inertia clearer than with the rhino horn trade debate. Having investigated the rhino horn trade since 2012 and been actively involved in demand reduction campaigns between 2014 and 2019, the continued push for an international legal trade resulted in Nature Needs More stepping off the rhino horn trade merry-go-round in 2019. While Nature Needs More hasn’t completely shelved the idea of doing more rhino horn demand reduction adverts in the future, we would only re-launch the campaign if the push to legalise the international trade in horn is once and for all taken off the table.

If it takes 13 years to NOT make any useful progress for one of the most iconic species, then what chance do the other 1 million species at risk of extinction have? The scale of the inertia is quite staggering.

Limitation 4: The Limiting Belief To Keep All Messages Positive

The belief in many circles that all messages should be positive, don’t upset people; people only learn and change when they feel positive and are having fun is both naïve and just plain wrong.

If this were true, then from a media perspective why don’t anti-smoking adverts show happy people playing with their children and saying “I have much more energy to play with my kids because I don’t smoke” or road safety adverts with drivers saying “Home again safe and sound because I don’t drink and drive”. Do you think such adverts would reduce the smoking rate or the incidences of drinking and driving? Unlikely!

Discomfort triggers behaviour change.

One of the fastest ways to trigger a behaviour change in the consumer group is for a campaign to eliciting negative emotions, in the moment, with the target group.

There is an over-generalisation of the behaviour change model that states don’t use fear or negative messages as this will stop people engaging.

While this approach is very necessary for campaigns that need to encourage people to go for a health check, especially when they think there is a problem, there is a misguided notion that this type of approach should also be used with people who are not intrinsically motivated to change.

When someone is not intrinsically motivated to change their behaviour, only one option is available to trigger a transformation; make the pain of not changing their behaviour greater than the pain of changing.

That is why one of the world’s most accomplished behaviour change experts, from the anti-smoking field stated, “Negative messaging campaigns do the grunt work. Positive messaging campaigns make them palatable for (government) donors to fund.”

The reality is, some people are motivated into changing their behaviour for positive reasons, but many need to feel discomfort to trigger them into action to do something different. This is used in the media to great effect, in the 1950s Listerine antiseptic adverts – don’t be rejected because of your bad breath.

To drive behaviour change to reduce demand, campaigns need to trigger emotions such as Status Anxiety and Health Anxiety.

Limitation 5: Massive Willpower To ‘Not’ Conform

Social status, identity and self-worth are more-and-more strongly linked to consumption. Most luxury consumers link rarity to higher status. Because basically all of the trade in endangered and wild species is a ‘luxury good’ – fashion, jewellery, fragrance, décor, gourmet food, exotic pets – exploring how to trigger status anxiety is usually a good place to start for any demand reduction campaign.

The paradox is that luxury consumption for status gain is both tribal and competitive. Tribal because meaning is conveyed primarily to the ‘in-group’, with almost everyone wanting to be seen as equal to their rich peers consuming the same ‘luxuries’. But social differentiation inside the group is also sought after, through the relative level of consumption and types of goods, services and experiences purchased.

When thinking about the potential effectiveness of demand reduction in this context, it must be acknowledged that opting out of the current consumption addiction requires both a secure identity and massive willpower to ‘not’ conform. At present, there is no status gain from not consuming these luxuries. On the contrary, not conforming will lead to status loss and potential expulsion from the peer group.

Therefore, demand reduction campaigns in this setting are likely to be ineffective without offering a viable alternative for differentiation and status gain without the risk of being ostracised.

This will require bringing back an old concept from a time when luxury consumption was seen as vulgar – the concept of magnificence.

Magnificence was about gaining status from contributing to society – such as building cathedrals or libraries or other investments that were both a public good and a ‘shrine’ to the donor. This still exists today in diminished form in contributions to the arts and universities, albeit because the donations tend to go to facilities frequented by the rich it is not really a public good.

In relation to the luxury consumption of endangered species we need to pivot to magnificence in the form of restoring nature, investing in rehabilitation and rewilding. Whilst there is public demand, and appreciation in some circles for ‘saving’ the environment, it currently does not present an opportunity for status gain in the circles that consume endangered species. Without this opportunity, there is no chance of stopping consumption via demand reduction campaigns.

The positive messaging to go with demand reduction needs to revolve around the magnificence of those who have made the switch from consumption to contribution. With sustained investment, the time is probably right for a transition back to magnificence.

Limitation 6: The Myth of Needing Species Data

As with all other aspects of conservation, in demand reduction there is a myth of needing more ‘baseline’ data on the target species being consumed before demand reduction campaigns can be created.

So, all too often time is wasted finding out more about the current status of the target species, while little is invested in understanding the underlying self-identity drivers of the key consumer groups.

In the case of demand reduction, the only species we need to understand is the consumer.

The conclusions of the 2019 IPBES report, that trade is the biggest extinction risk for marine species and the second biggest risk for terrestrial and freshwater species, means, when creating demand reduction campaigns for species that are commercially traded, the best strategy to assess the current population status is to assume the worst and put all the effort and responses into campaign action. The scale of the crisis associated with biodiversity loss was acknowledged as early as 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Rio de Janeiro Conference or the Earth Summit.

At the 1992 Earth Summit the Precautionary Principle (Principle 15) adopted stated, “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

Yet, in the intervening 30 years, the conclusion of nearly all conservation research is there is a need to gather more data. It must be acknowledged that this happens because collecting data is the key method for conservation organisation and academics to get funding. Let’s face it, they don’t get funding for rigorously and independently policing commercial sustainability processes and their results. We would probably get better outcomes in tackling biodiversity loss if they did!

For demand reduction and consumer behaviour change the only data needed is the psychological drivers and influences of the key consumer groups. The type of data companies call on marketing and advertising agencies to collect via focus groups, interviews and questionnaires.

Firstly, target the right person and forget the rest who just ‘appear’ to be a part of the same group.

The data gathered will be useless if the wrong target groups are used for interviews and surveys. A good example of this is a paper published by the International Trade Centre in 2017 titled: Demand in Viet Nam for rhinoceros horn used in traditional medicine. The ITC said they conducted a survey of 1,000 consumers of TAM, including 239 people who self-disclosed they used rhino horn.

But when you look salary information collected, and knowing the price of rhino horn in Viet Nam at the time, all the ITC can say is that some of the 50 people in the top income bracket surveyed MAY have a sufficiently high disposable income to afford illegally poached genuine rhino horn.

They can’t prove if they surveyed anyone earning a sufficiently high monthly income to guarantee they were (consistently) buying genuine rhino horn in relevant quantities.

If you just look at the wealthiest monthly income quoted, then a person earning this would need to spend their entire monthly income to buy 10grams of rhino horn! In this instance, the group interviewed is simply not relevant to the issue being investigated. Any conclusions from this research dataset about the rhino horn trade is simply useless. It is the campaign equivalent of LVMH interviewing welfare recipients to make decisions on future advertising campaigns.

Secondly, Beware of Virtue Signalling

Even if the right target group is being interviewed, some will adopt a ‘virtue signalling’ response, not wanting to be perceived as ‘bad’ people or feel guilty or ashamed of their purchasing. Over a decade ago Gao Yufang, researcher and conservationist, made it very clear that, “ivory investors know a lot about ivory, and they know a lot about elephant poaching”, continuing, “They distinguish the different types of ivory—they say it’s yellow, white, or blood ivory. These investors openly say that blood ivory is from [a] poached elephant. And the ivory was got when the elephant was still alive. Of all the kinds of ivory, blood ivory is the most expensive. So they know exactly where the ivory comes from”. This confirms that campaigns created by conservation in the belief that the consumer doesn’t know (elephants are killed to get their ivory) and simply need to be educated, are unlikely to be useful.

In creating a demand reduction campaign, work on the principle that consumers know and they aren’t intrinsically motivated to change.

Model Defining Demand Reduction

To clarify the difference between demand reduction, education and awareness-raising Breaking The Brand created a model in 2014 outlining how we would define each of the different types of campaigns. When you look at campaigns through this filter you can see that very little (and for some species nothing) has been spent on genuine demand reduction campaigns.

While the social validation of running genuine demand reduction campaigns is happening, progress is too slow within the global conservation players. There is a reluctance to cause discomfort in their adverts even when empirical research demonstrates that discomfort can trigger behaviour change in groups that aren’t intrinsically motivated to change.

Demand reduction campaigns can be a part of the strategy to help tackle biodiversity loss but only if large conservation and donors take it seriously. This includes accepting consumer demand reductions limitations, including what is outlined here and, in addition, conservation’s blind faith in the sustainable use model together with the poor quality of trade regulation.

How to Create and Evaluate Demand Reduction Campaigns

There are a number of steps that you should follow when designing a demand reduction campaign for illegal wildlife consumption, these steps are:

- Identify the user groups for each of the different products or different uses

- Find out the true motivations to use the products

- Summarise the patterns

- Derive potential reasons to stop using and calibrate with target group(s)

- Identify the most effective communication channels

- Design campaign messages and test

More tips, tools and ideas to tackle the demand for endangered species can be found also found via BTB Blogs.