As many of you who have been following Breaking The Brand (and now Nature Needs More) know, I have previously expressed my concern about the lack of ability (or willingness) of the large conservation organisations to challenge the current, rhino horn pro-trade agenda.

Pro-trade advocates are happily stepping in to the void left by large conservation in this regard. They have created and honed simple, catchy messages that give the uninformed public the impression that current conservation efforts tackling the illegal wildlife trade are failing (which is largely correct) and that only allowing people to make money from exploiting them, if it pays it says approach, can ‘save’ them (which is a blatant lie).

In recent times, pro-trade groups wanting to sell rhino horn have stepped in to the conservation leadership void and managed to push through domestic trade laws in South Africa; now they are advertising a rhino horn auction without any permit system for a domestic trade being in place. In doing this they are pushing & testing the boundaries and assessing the level & nature of the push back.

So, the question is, if large conservation agencies are accepting farming as conservation, is what is being farmed still wildlife? Is it conservation to farm wildlife?

Elephant in the room 1: Does Farming = Conservation?

In my eyes, it does not. This is a critical consideration, as it underlies the whole premise of most of the large conservation sector – the support of the ‘sustainable use’ model. For example, in a recent blog about the upcoming rhino horn auction in South Africa: https://www.savetherhino.org/rhino_info/thorny_issues/john_humes_proposed_rhino_horn_auction SRI states “In principle, Save the Rhino supports sustainable use”. They are not the only conservation organisation to make such statement; which is the reason for my question: does farming = conservation?

If we take a look at images of rhino farming, we see rhinos feeding from troughs as you would expect farm animals like cattle to do. Yet we never refer to cattle farming as ‘cow conservation’, do we? So why should rhino farming be considered conservation? How can something that is explicitly designed to support human needs – farming – be classed as wildlife conservation, which surely is about animal needs? And if ‘sustainable use’ is NOT supposed to be farming, then what is sustainable use of rhinos?

The problem is that we tend to accept common terms, like ‘sustainable use’, which have been hammered down our throats for decades, without thinking about the what this ‘really’ means and the actual implications for a particular species. Conservation tries to sidestep the issue by using sanitized or vague terms, such as sustainable use. We need to challenge the conservation bodies, that supposedly look after the interests of wildlife, to stop using the term and spell out what they really mean in each instance; trophy hunting, farming etc

Elephant in the room 2: Farming = Trade = Understanding Customer Desire

Now if conservation organisations hold the belief that Farming = Conservation, and are saying, in principle they support sustainable use, then you have to assume they have done the research to back up their support of a system where Farming = Conservation, which in my mind means that they have spoken to the people who are driving the current rhino killing spree to see if they would accept a farmed product as a substitute for the ‘genuine’ wild article.

Before I write more on this, I will firstly link you to previous articles I have written:

- September 2015 blog: Farmed Rhino Horn Not Seen As Substitute Product highlighting horn from a farmed rhino will not help solve the rhino poaching crisis, as it is not seen as a substitute product by the Vietnamese elite who can afford genuine, wild rhino horn. This may be the reason for the following (from the linked article): When Independent Media visited the property last week close to 100 rhinos could be seen munching from feeding troughs in an area the size of a large soccer pitch……. [Hume] also bristles at suggestions that his rhino ranch is little more than a semi-industrial cattle farm: https://www.africahunting.com/threads/meet-the-world%E2%80%99s-largest-rhino-breeder.36099/ There seems to have been a lot of images of this high density, supplementary feeding in recent years.

- June 2016 blog: Smart Trade – NO, Foolish Assumptions – YES highlighting the significant assumptions in the pro-trade business plan (if it can be called that); this document can be found on the pro-trade website: http://www.rhinoalive.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Michael-Eustace-Smart-Trade.pdf together with their statement that it provides the evidence they can supply the market. To-date, other than the odd comment, I haven’t seen much evidence of large conservation groups challenging the pro-trade assumptions made in this document.

- April 2017 blog: A Load Of Bollocks highlights published research, that concluded that users would accept horn from a farmed rhino, is invalid if the people surveyed have such low incomes levels that they can’t actually afford genuine rhino horn.This is like basing sales projections of LVMH handbags on interviews with people on welfare – it’s simply rubbish science.

When I asked Save the Rhino the question about what they believe in regard to the users’ desire for a farmed vs wild product, the response was “we have not been involved in conducting any formal research in the area of what consumers say they would and wouldn’t purchase”. I would say that, if they believe that they need definitive research before they would be able to make a comment on this, then why hasn’t the leading rhino charity in the world commissioned such research? Why did they, and others, leave the field to South African and Vietnamese to commission flawed research via the ITC (point 3 above)?

I believe there is sufficient evidence highlighting that the Vietnamese elite want ‘wild’ to warrant a comment. Rebecca Drury of FFI published work on this in 2009 and a paper published last year, with a very similar focus and findings to Rebecca’s earlier work: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0134787 In the conclusion, this paper states: “For a ‘super-elite’ segment of Vietnamese society, whose members consume wild sourced animals to convey status and wealth, farmed sourced wild meat is not an appropriate substitute as it lacks the product characteristics needed to symbolically convey status and wealth-expense and rarity. Indeed, it is possible that the availability of substitutes in the market is causing these consumers to place increased emphasis on finding the rarer, wild specimens to assert inter-group differences in status and face. Where combined with a willingness and ability to pay rising prices, this could incentivize the exploitation of the last rare, wild individuals of farmed species or alternatively, shift demand to those species whose biology precludes their being farmed.”

There are a few things to point out with this:

- If NGOs want an evidence based approach, then my question is, why have they not done this research over the last 7 years as the poaching crisis took hold?

- I am not sure why conservation groups can’t make an intuitive link from the research in to the wild meat restaurant trade in Viet Nam; the elite customers they researched, who want wild sourced meat, are the same elite users group who buy rhino horn. As I have mentioned previously, we need leaders with strategic intuition in the conservation sector, who can make insightful leaps.

- In the end, they need to remember that significant number of high status males will not be interviewed in such a way that their answers about their illegal use of rhino horn can be recorded for scientific research and publication. It would be like asking top-level businessmen and public servants in the West/English speaking countries to talk about their levels of cocaine use, for scientific research and publication.

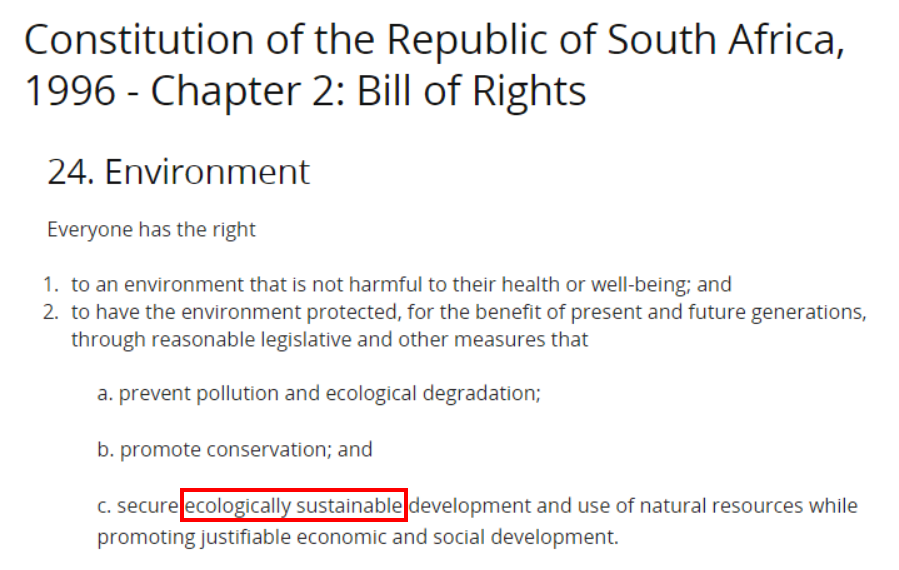

- They ignore the Rio precautionary principle: Importantly, Principle 15 of the 1992 Rio Declaration sets out the Precautionary Approach “where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.

If you really want to know if the is a basis for supporting rhino farming (irrespective of its desirability or validity as a ‘conservation’ measure), then you have to start with consumer research first; and accept that you most likely need experienced cultural anthropologist for this type of research. Similarly, the users weren’t mentioned in a submission to CITES CoP17, African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade, by key rhino NGOs. When I have discussed this preference for wild horn with individuals working a key wildlife trade agency, I was told that an opinion on an a ‘legal’ trade is not within their mandate, so they didn’t make it part of their consumer research. Surely, what is right for the animal should be the priority, not the scope of an organisations mandate?

Elephant in the room 3: Why is a trade regulation body (CITES) and not a conservation body the primary agency and arbiter in this space?

When I think about this I always go back to one on my earliest managers. Whenever he felt that a decision or process was based on the wrong premise, his response would be “Well that’s a bit arse over tit isn’t it?”.

“CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is an international agreement between governments. Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival.” (from the CITES website)

If you read these two sentences carefully you will recognise that CITES looks at trade first, conservation second. The need for trade is taken for granted, the need for conservation is the afterthought to ‘make the trade sustainable’. Of course, CITES has no actual mechanism for making the trade sustainable or even regulating it. All it has is a system of ‘trade exemptions’ (listing in Appendix 1 and 2) and a permit system for trade. Both tools are crude, flawed and subject to the varying effectiveness of ‘national implementation’ efforts by each of the signatories to the convention. Even advanced economies, such as Australia, do in fact very little when it comes to implementing the convention.

We have had 40 years during which a trade body has been the primary facilitator of ‘conservation’ and we all know the crisis in the natural world has got much worse. Is it not time that an International Nature Custodian body should be given this role?

Elephant in the room 4: Is the CITES database/permit really system fit for purpose?

As some of you may know, I have been supporting a local initiative in Australia (Donalea Patman: http://fortheloveofwildlife.org.au/ ) and New Zealand (Fiona Gordon: https://gordonconsulting.org/completed-projects/ ) pushing for a total ban on the domestic trade for elephant ivory and rhino horn, no matter the age. As part of this project, research was done to assess the number of ‘legal’ elephant ‘products’ (mainly ivory, some skin) exported from the UK to Australia; given the UK was named as the world’s largest exporter of legal ivory: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/aug/10/uk-named-as-worlds-largest-legal-ivory-exporter The result:

- Import and export permit records between countries don’t match: Elephantidae specimens

- UK exports to Australia 2010-16: 2298 ‘units’*,

- Australian import permits from UK: 1 ‘unit’*, covering the same time frame

- A mismatch of 2297 ‘units’.

*Next to no information on what constitutes a ‘unit’.

Even after considering some of the legitimate reasons why they don’t match, such as people getting the permit to export but then trade didn’t happen, this is a BIG discrepancy.

When the local CITES representative was asked about this, we were told “You don’t really need an import permit, it is up to the exporting country to do the due diligence on the country to where the item is being sent.” Back to the elephant in the room, how does this statement make the findings better? It doesn’t prove that there is a way of cross-checking if the exports from the UK to Australia arrived here as the designated destination country.

When speaking to representatives of large conservation organisations about this the response was “Yes, we know it isn’t great, but it is all we have.” But this is not about a mediocre system, it is about a system that certainly appears like it won’t pass the most basic audit, let alone a forensic one; has this been the case since it was set up?

There is a belief from some that this problem with the CITES database/permit system shouldn’t be talked about too loudly, in case the traffickers get wind of its failings. Well, news flash, they know and they are taking advantage of it, this is what we were told by customs and ex-customs representatives who we interviewed as part of the research.

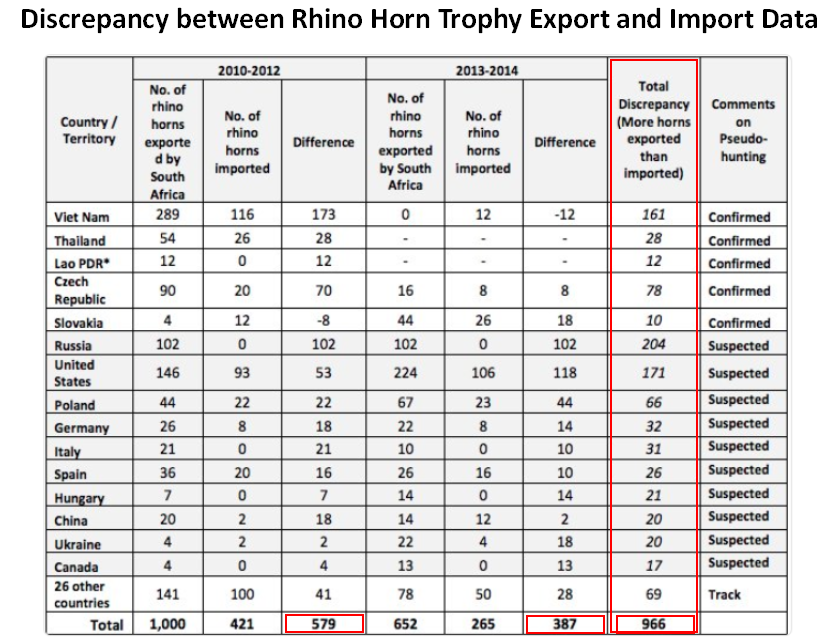

Specifically, for rhino horn, the table shown was introduced at CoP 17 and again the discrepancies highlighted are concerning.

In summary, there is no evidence that CITES have invested into an auditable system of trade that makes it sufficiently difficult for traffickers of illegal wildlife products to rely entirely on smuggling. In addition, there are concerns about the South African Government permit system.

The costs of upgrading to a fully auditable and watertight system of trade and trade permits should be borne by those who want to trade, who benefit from it and who enable it.

Elephant in the room 5: The illusion of CITES signatory responsibility

Australia likes to pride itself in having tough wildlife legislation. In theory, at least, Australian legislation for these types of wildlife crime appear significant: up to 10 years imprisonment or up to an AUD $180K fine. In practice, the situation is quite different. Between 2010 and 2016 nearly 450 seizures of rhino horn and ivory happened at the Australian border. None of these seizures resulted in a fine or prosecution; just a confiscation; this doesn’t even constitute a slap on the wrist.

As a result, we would say that a transparent and honest country scorecard should be implemented, for both signatory and non-signatory countries, one that realistically assesses the ‘genuine’ action a country has taken to address the illegal wildlife trade.

The Australian Commonwealth Government:

- Is a signatory to CITES,

- In February 2014, it also became a signatory to the declaration resulting from the London Conference on the Illegal Wildlife Trade: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/281289/london-wildlife-conference-declaration-140213.pdf

- As recently as July 2017, as part of the G20 it became a signatory to G20 High Level Principles on Combatting Corruption Related to Illegal Trade in Wildlife and Wildlife Products: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/news/pr/2017/2017-g20-acwg-wildlife-en.pdf

Signing up to such agreements, declarations or principles is of little value if no serious actions are taken to address the illegal wildlife trade, not just on our borders, but also the laundering of illegal items into our – still entirely legal and unregulated – domestic trade. Australia has a lot more to do on this front.

In conclusion

There is a herd of elephants in the room!

Elephant in the room 1: Does Farming = Conservation?

Elephant in the room 2: Farming = Trade = Knowing What the Customer Wants

Elephant in the room 3: Why is a trade regulation body (CITES) and not a conservation body the primary agency and arbiter in this space?

Elephant in the room 4: The CITES database/permit system is not fit for purpose

Elephant in the room 5: The illusion of CITES signatory responsibility

As we get closer to the rhino horn auction, we must ask conservation organisations to make clear statements on what they support; do they support farming of rhinos and, as a result, can they clarify how farming = conservation?

As we head towards the 4th International wildlife Trade conference, in the UK in October 2018, do concerned citizens around the world request that:

- Resources are put in to significantly upgrading the CITES database/permit system to bring it up to the standards needed to stand up to a forensic audit and protect wildlife

- A robust signatory score card system is developed that rates a country on the ‘genuine’ actions it is taking to address the illegal wildlife trade, not just on our borders, but also to ensure laundering of illegal items into legal domestic markets is impossible.

- A transition to an International Nature Custodian body, and away from a trade body, being the primary agency and arbiter facilitating decisions on protecting the natural world.

And finally, given all this will take time to implement, do concerned citizens request trade moratoriums be implemented for critical species whiles these are being designed, implemented, tested and confirmed to be fit for purpose. Surely, it’s time to take the protection of wildlife seriously.

These are the views of the author: Dr. Lynn Johnson, Founder, Breaking the Brand and Nature Needs More