In 2017, I wrote an article, Want To Know Why Conservation is Failing? Read On. In the article I quoted Vikram Mansharamani, a lecturer who teaches “students to use multiple perspectives in making tough decisions”. Mansharamani uses the analogy, if we think in terms of a forest, organisations around the world have come to value expertise and, in so doing, have created a collection of individuals studying bark. There are many who have deeply studied its nooks, grooves, colouration, and texture. Few have developed the understanding that the bark is merely the outermost layer of a tree. Fewer still understand the tree is embedded in a forest. This analogy regularly springs to mind as I read policy recommendation documents created by the conservation sector.

And so again this is the case as I read WCS’s Recommendations regarding CITES Standing Committee 78 agenda items. Specifically, WCS’s statement on traceability in the World Wildlife Trade Report section, “Furthermore, the introduction of concepts such as traceability confuse the core mandates of CITES with specific approaches that may only be outlined in CITES resolutions.”, continuing, “that time would be better spent assessing progress towards the delivery of the negotiated CITES Strategic Vision.”.

Let me repeat that “the introduction of concepts such as traceability confuse the core mandates of CITES”. So, should we take statements on sustainability and legality of the use of wild species in trade simply on blind faith? As both the World Wildlife Trade Report and the CITES Strategic Vision document where mentioned, what is the difference between them?

The CITES Strategic Vision talks about making all trade sustainable and legal, in line with the KNGBF. The CITES inaugural World Wildlife Trade Report, launched in 2019, talks about sustainability, legality and traceability. While I am no fan of the CITES World Wildlife Trade Report, at least it does acknowledge that CITES is a trade convention.

Adding traceability is a requirement for supply chain transparency, and not something that ‘confuses the core mandate’ of CITES. How can there be proof of sustainability, legality and indeed safety without traceability? You simply can’t have one without the other. Without traceability there is no audit trail, there is no supply chain transparency and because the CITES trade data is of such poor quality there is no proof of the sustainability statements luxury brands make in their glossy reports.

It is the growing demand for proof of sustainability and legality that is the problem for many organisations who have simply relied on blind faith in the system to-date. Even with their evidence-based mantra, for the legal trade they have been willing to sidestep George Henry Lewes recommendation of, “We must never assume that which is incapable of proof”. The sad thing is that with a very limited investment into traceability, CITES trade could take one step closer to being much more transparent. Some believe this hasn’t been done in the two decades it has been discussed, because too many stakeholders want to maintain plausible deniability on the scale of the legal trade in CITES listed species.

But now that there is a growing acceptance that traceability is necessary, it needs to be funded. So, let’s be honest, this whole argument comes about because of the limiting belief that CITES related funding can only come from governments and will not increase.

As one retired FWS representative said recently, “many people don’t realize that CITES is designed to facilitate legal trade”.

Within trade, traceability is a business responsibility, and businesses need to be held to accountable for traceability. The tragedy is that for the last 50 years, business has been allowed to take an all profit, no responsibility approach which has led to overextraction, overproduction and overconsumption. It is long overdue that their lack of care in ensuring their offtake of endangered species is proven to be sustainable and legal has a negative impact on their brand and share price.

For decades, as populations of wild species have plummeted, business funds have been used for advertising and marketing, driving up the desire for goods manufactured using endangered, rare and exotic species. It should not come as a surprise that the legal trade in wild species is a key driver of biodiversity loss. The reason it has reached the crisis stage is because there has been no traceability, and in turn, no proof of sustainability and no proof that the raw materials used in manufacturing were legally sourced or within quota limits.

In the section on the World Wildlife Trade Report, WCS further voices the concern that, “For example, using phrases such as “socio-economic impacts” could result in a vast compilation of unstandardized data or inputs”. This is again disingenuous. Why would WCS have a problem with a ‘vast compilation of unstandardised data’ given the organisation, along with others, has accepted CITES trade data that relies on a 50-year-old paper trade permit process, which is wide open to fraudulent use, because terms such as ‘various’, ‘unspecified’, ‘unknown’ and ‘specimens’ are allowed and because any process of transcribing from paper is always error-prone.

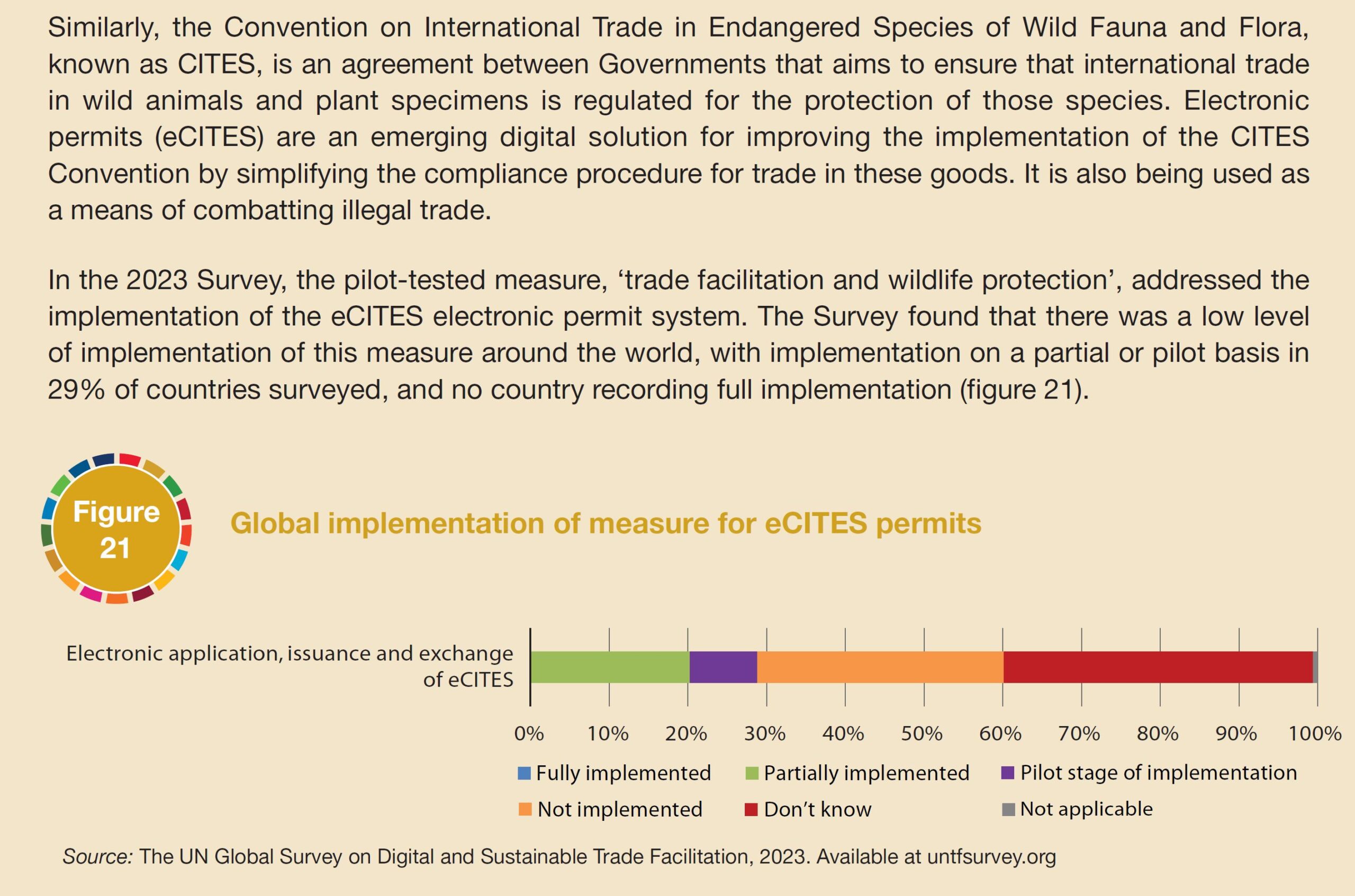

The option of moving to a modern, digital trade permit system has been on the table since 2002 and available as an off-the-shelf solution for several years. Why isn’t WCS advocating for eCITES, which would force consistency and standardisation, in data and inputs, in in real time?

What is unstated in these recommendations, as with many others from establishment conservation organisations, is that they want CITES to stay within its self-imposed, narrow constraints of listing proposals and NDFs. These narrow constraints almost always coincide with the activities conservation organisations get funding to do. All too often, such self-serving arguments smack of protecting revenue streams, not of a desire to truly improve CITES trade regulation. 50 years of staying withing these self-imposed constraints have provided zero evidence that trade is sustainable and/or legal.

It isn’t unusual to see contradictions in these policy documents and this one is not different. When it comes to traceability, the document states, “Furthermore, the introduction of concepts such as traceability confuse the core mandates of CITES with specific approaches that may only be outlined in CITES resolutions.”. Yet in the section about OneHealth, the WCS recommendations advocate to go beyond those same ‘core mandates’, “International wildlife trade is one of these factors, and of course all international wildlife trade (other than that from areas beyond national jurisdiction) begins domestically. As such, these issues are highly relevant from a CITES perspective.” Domestic trade is outside the remit of CITES, not just its ‘core mandates’, and has only been addressed in CITES resolutions.

If these recommendations are more about ongoing access to funding rather than better regulating the wildlife trade, this would be a sad indictment of the state of the conservation sector.

Because we can get funding for doing NDFs we support these actions but we can’t get funding for traceability, so we see it as a distraction – “the introduction of concepts such as traceability confuse”. If this is the case, it would be because of their inability to see the solution to the CITES funding problem lies outside the self-imposed, narrow mandate.

While the policy document discusses collaboration with a number of UN bodies, namely UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime), UNTOC (UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, UNCAC (UN Convention against Corruption), it leaves out UNCTAD (UN Trade and Development). UNCTAD partnered CITES to develop an off the shelf CITES electronic permit system. In UNTAD’s last UN Global Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation report, it acknowledged the slow pace of modernisation of the CITES trade facilitation system:

The primary objective of CITES is to regulate the legal trade of a growing number of endangered and exotic species. As such, traceability is and should be a ‘core’ part of its function. Trade is conducted by business and much of CITES trade is for the luxury sector that literally has tonnes of money.

The logical step would be to advocate for companies selling the end products to pay their fair share and no longer accept the ‘all profit, no responsibility’ behaviour of business. Have we have ended up in this situation because the establishment conservation organisations are more interested in getting business sponsorship than holding business to account?

Business can and should pay for traceability. Nature Needs More outlined in detail how a business contribution can help Fix the CITES Funding Crisis. This can be done in the current CITES model without the need to change the articles of the convention.

The so-called evidence-base of the legal wildlife trade needs be urgently fact-checked. Only with good quality traceability is that possible. Why do establishment conservation organisations see this as confusing?