Having followed the rhino horn trade debate since 2012 and been actively involved in demand reduction campaigns between 2013 and 2019, I have been struggling about how to recognise World Rhino Day 2024, or even if indeed I would.

While Nature Needs More hasn’t completely shelved the idea of doing more rhino horn demand reduction adverts in the future, we would only re-launch the campaign if the push to legalise the international trade in horn is once and for all taken off the table. To do anything else would be futile, like Sisyphus for eternity rolling an immense boulder up a hill for it to roll back down every time it neared the top.

Hence this is likely my last World Rhino Day blog, so please bear with me as it is long. From now on I might dust it off every year and post it again, to see if anything has improved the plight of the rhino.

Since I have been watching the space, nothing has shifted the dial to save rhinos. Over the years, there have been glimpses of hope, that have all too quickly wilted as a result of the conflicting interests of some stakeholders. Undoubtedly, one key reason for the lack of progress is that NGOs and academics have accepted (or been bullied into) an incrementalist approach. This may be OK if it was the 1970s but it isn’t, and tipping points are on the horizon.

Just one part of the incrementalist approach is for generation-after-generation of young conservationists to do the same research over-and-over again. I look forward to a time when this cycle is broken. In the same way, pilot projects are repeated every few years; and even if proven effective, they are never scaled and are just left to wilt.

Another part of this incrementalism is conservation’s lack of willingness to come out of its rabbit hole and make insightful, intuitive links from research in other sectors, for instance the health, luxury and advertising industries. While I will explain this with rhino examples, because it is World Rhino Day, I could just as easily used elephants, pangolins, sharks, pythons, crocodiles or macaques – basically any number of species.

If it takes 13 years to NOT make any useful progress for one of the most iconic species, then what chance do the other 1 million species at risk of extinction have? The scale of the inertia is quite staggering.

Rhino Horn Trade Debate#

The South African (SA) Government is pro-trade, but it can’t really move on this until it proves to the world that the legal trade of rhino horn can be managed without further endangering the species. Together, the SA government or pro-trade private rhino owners have proposed scenario after scenario aiming to demonstrate trade can work, ranging from:

- Flood the market (too few rhinos left),

- One off sale of stockpiled horn (one off sales of ivory stockpile proved that this doesn’t stop elephant poaching, 2017),

- Restricted supply cartel-like model (this would keep the price fixed and high, so still lucrative for poachers, 2016),

- Legalise domestic trade in South Africa and sell locally (who cares if it is smuggled out of the country once we have made our money, 2017),

- Online Auction of rhino horn in South Africa (multilingual website in English, Mandarin and Vietnamese even though if you buy horn, it couldn’t leave the country!, 2017),

- Cryptocurrency ‘RhinoCoin’ (why legitimise strategies used by wildlife traffickers?, 2021),

- Rhino horn medial tourism (pushing the ridiculous notion that people in Asia don’t evolve, 2015)

The SA Government has its own example of going around in circles, with several enquiries into the trade of rhino horn over the years. In all this time it hasn’t been able prove to the global community that an international legal trade in rhino horn can work, even with the support of neutered conservation agencies. While in South Africa in 2015 meeting with representatives of the rhino horn no-trade and pro-trade camps, I was told that no international conservation agency working in the country was going to oppose the SA government’s desire to sell rhino horn. If they did their licence to do research in country could be revoked (so they would lose international donations) together with significant levels of SA government grants.

Given the SA Government’s desire to supply, the mixed messages this sent to demand side countries resulted in Nature Needs More stepping off the rhino horn merry go round in 2019. But over the last 5 years we have monitored the debate, as it continues to go nowhere, and rhinos continue to be killed.

One interesting period was during the pandemic, which saw a reduced interest in wildlife consumption in key destination countries. There were significant price drops in the value of rhino horn, and not increases as it became harder to find. So, it was very interesting that a publication of the Wildlife Justice Commission during this period stated, “up to one-third of rhino horns seized globally may have originated from legal horn stockpiles”. With just a slight modification to The Salesman’s Mantra, you could say that, “Sales tricks are what you use to sell something to someone who isn’t interested in a product any longer”.

One of the bright moments in recent years was when John Hume’s rhinos were sold to African Parks to be used for rewilding. But this was tempered by the knowledge that the result of this sale meant a massive amount of cash was available to lobby for an international horn trade. Hume’s horn stockpile was not included in the sale; in the end it was the horn Hume wanted, not the rhinos given the costs of security.

Hume started breeding rhinos in 1992, just 12 months after the one of the final acts of the Apartheid government. In June 1991, the Game Theft Act was passed permitting landowners to have ownership rights over wildlife within fenced areas. The Act made South Africa one of a few countries globally where wildlife can be privately owned. After 30 years, the Hume family sits on a massive stockpile of rhino horn, as does the SA government.

The Current State Of Play Of The Rhino Horn Trade Debate#

The merry-go-round continues with the new draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy of the SA government. When it comes to rhinos, the SA government proposes setting up “health clinics to administer traditional remedies using rhino horn for health tourists from the Far East”. The medical tourism fallacy was proposed previously in the run up to South Africa hosting CITES CoP 17, in 2016. It was rejected then and had been taken off the table for a while, but the never-ending desire to turn rhino horn into dollars means that any half-baked idea will be resurrected if it makes an argument for legalising the trade.

The fact that the SA government and private rhino owners are sitting on an enormous stockpile of rhino horns from (legal) dehorning means that the government is constantly pushing the boundaries to try and circumvent the international trade ban for rhino horn, in place since 1977. After successfully overturning the domestic trade ban for raw rhino horn in South Africa in 2017, pro-trade private owners have now managed to lobby the government to include a potential trade in processed horn as part of a larger draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy. The name says it all, really, but in case of any doubt: “the stated purpose of the NBES is to optimize biodiversity-based business potentials and contribute to economic growth while maintaining the ecological integrity of the biodiversity resource base for thriving people and nature.”

The NBES talks explicitly about creating a market for medical tourism from the “Far East” to South Africa so that tourists can buy powdered rhino horn for personal consumption, and also states they should also be able to buy horn carvings.

Of course, this means overturning the existing ban on the sale of processed rhino horn in South Africa and it will guarantee a run-in with CITES as the ‘personal effects’ exemption under CITES does not apply to Appendix I listed species. There is always the possibility that, as with elephants, SA will try to move its white rhinos to Appendix II. This type of split listing for elephants, with some countries having a species on Appendix I while others have it on Appendix II, has caused significant tensions. Either way, ensuring the legality of supply of powdered horn or small carvings will be impossible without expensive DNA testing, that no one will be willing to pay for.

So, the government will do what everybody does when it comes to conservation – look the other way and keep going on about the economic benefits. This is not conjecture, it has already happened as a result of the South African governments legislation to allow a domestic trade in rhino horn in 2017. At the time, Izak du Toit, one of the Hume teams legal representatives working on overturning the domestic ban on rhino horn, said, “We would sell [rhino horn] to the poachers to prevent them from killing rhinos” and acknowledged that rhino horn will have to be smuggled from South Africa to Asia in order to find a market.

The economic benefits in the draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy are simply the potential windfall for the pro-trade owners of private horn stockpiles, nothing else. The government does their bidding and conservation agencies protest a bit but lack the courage to confront the system that continuously comes up with ever new ‘innovative’ ways to sell off nature and make some people rich(er).

Simultaneously the SA environment ministry is preparing a plan to submit to national cabinet with the aim that “conditions are met for legal international trade in rhino horn from protected wild rhinoceros, for conservation purposes, to be promoted”. Once such a plan has been approved nationally it would then need to be taken to a CITES Conference of the Parties. For ‘optics’, the plan will talk extensively about the supposed ‘conservation purpose’ of dehorning rhinos and selling stockpiles and won’t mention any of the evidence that legalising the trade will inevitably boost demand. Just one reason being, if trade is made legal, horn can be legally marketed and advertised. All you need to do is compare smoking rates in countries where cigarettes can still be legally advertised to countries where such advertisements are prohibited. This isn’t rocket science.

And, in all this time those who have the desire to supply have shown very little interest in understanding the consumers or the nature of the demand. Their business plan over the years has never evolved beyond, “Rhino horn and these other products are status goods, they are prestige goods. What they are used for is hardly relevant. The fact is that people are willing to pay extremely, extraordinary high prices for them”.

They have ignored that the users aren’t interested in chemically treated, stockpiled horn.

They have ignored the fact the users aren’t interested in farmed horn, which is even more apparent now with the fact that poaching of Asian rhinos has risen significantly.

They have ignored the fact the while the desire for rhino horn remains, the buyers want horn from a wild rhino. Wild rhinos have status to the wealthy buyers, farmed rhinos don’t. Farmed rhino horn is not seen as a substitute product.

Instead, they have pushed the propaganda that “Because the Chinese and people of SE Asia have used rhino horn in the past then obviously, they will ALWAYS use rhino horn because they are incapable of changing, so the only hope for the rhino is to sell rhino horn to them”. They have chosen to ignore the fact that, as with all peoples’ values, including those in relation wildlife and the natural world, they change over time. If we applied the same ‘people can’t change’ propaganda to South Africa, then the country would still have an apartheid government, Nelson Mandela would have died in jail and there would be no ‘born free’ generations.

People, cultures and societies change all the time, and this change can often be rapid. Such changes could be accelerated if more expertise and funds were directed at developing comprehensive behaviour change/demand reduction strategies for rhino horn, ivory, pangolin etc. Which is why Nature Needs More published demand reduction campaigns for 5 years in the first place.

Innovation and Technology#

As with most of the problems we are collectively facing, there is a belief from many that technology and innovation will save the day. This techno-utopia thinking allows a comforting fantasy in which science, technology and innovation will get the job done and means we don’t have to alter the current global policies enabling industrial overproduction, overextraction from nature, and promoting constant growth in consumption.

Science and technology are not enough. I’m a scientist by training, I love science. I completed my PhD in particle physics in the 1990s, creating a neural network to look for patterns to distinguish quark and gluon jets – complete nerd stuff! When I was approached with a job offer in the City of London, I turned it down. Recognising back then the problems of a financial system unwilling to accept its role in the climate crisis. Science and technology will never be enough to save species unless it can corral or trigger behaviour change in the people driving the extinction crisis. This is particularly important when it can drive change in people who aren’t intrinsically motivated to change.

When I interviewed the primary consumers of rhino all those years ago, to create the pilot demand reduction campaign, I discovered only 2 motivations would stop them using rhino horn:

- Health Anxiety: A perceived negative impact on the health of the user of consuming rhino horn, and

- Status Anxiety: A perceived negative impact on the status of the user (in the eyes of his peers).

The interviews uncovered that these consumers could not be influenced by messages about rhinos or animal welfare. Similarly, they could not be moved by the efficacy or otherwise of medical use, or the comparison of rhino horn to human fingernails or hair. They confirmed that they know it has no medical benefits; when they offer rhino horn to their peer group it is all about power and status. By doing so they are saying, “I am someone that you what to do business with, I am in a powerful position, and I have connections”.

Law enforcement messages don’t work for these men, who stated “I am not worried about prosecution”; they obviously felt they were (and indeed often are) above the law. The interviews confirmed that this key user group was not interested in campaigns that use media celebrities, saying “They are for kids” and “Celebrities can be paid to say anything”. The work clarified that there was no point doing any more research to prove there is no medical benefits to rhino horn or that it is just keratin. The consumers know and the don’t care. Yet this research keeps being done.

These 2013/14 interviews were used to create a model to clarify the difference between awareness-raising, education and demand reduction campaigns.

We defined a demand reduction campaign as one that, “elicits an emotional response in the current user groups to such a level that it triggers them to stop using rhino horn in a timeframe that is useful to save rhinos from extinction in the wild”.

From the interviews with the users, of the two motivations to change, health anxiety was by far the quickest to drive behaviour change. Fear, uncertainty and doubt has been used in the advertising of products for decades – in both getting people to buy products (e.g. mouth wash) and getting people to give up products (e.g. quit smoking).

Decades of evidence from anti-smoking adverts confirmed that, “highly emotive negative health effects messages motivate adults to stop smoking”. In a meeting with one of the worlds most accomplished researchers on anti-smoking campaigns, the ‘discomfort triggers behaviour change’ strategy was reinforced when she confirmed, “Negative messaging campaigns do the grunt work in getting people to quit. Positive messaging campaigns keep the donors happy”.

So, it was great timing that a SA organisation was testing something that could trigger health anxiety, namely infusing rhino horn initially with organophosphates before moving to ectoparasiticides and a red dye. An emotive, negative messaging campaign could be designed to raise the profile horn infusion in Viet Nam.

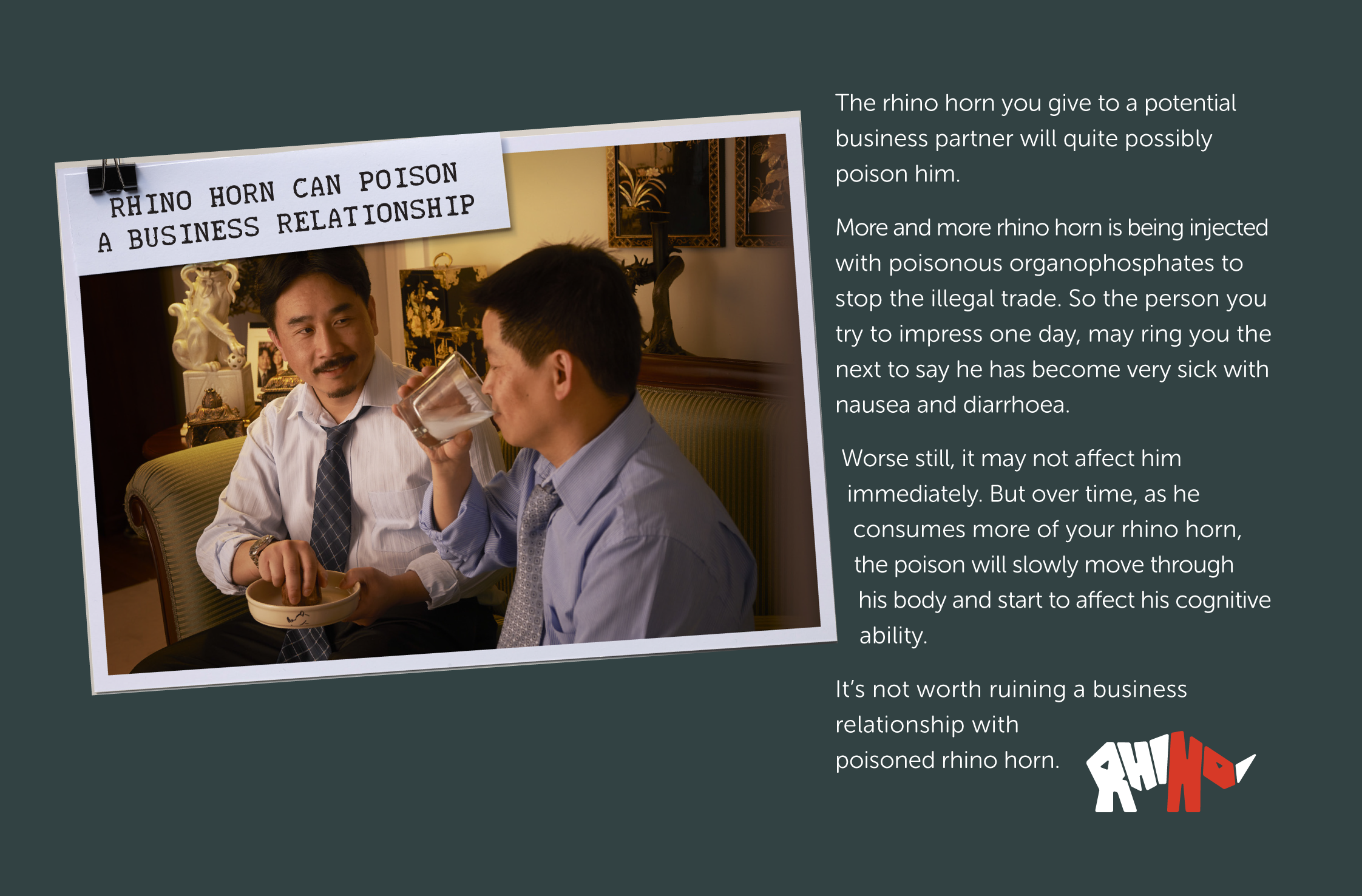

The Breaking the Brand (to stop the demand) campaign, Rhino Horn Can Poison A Business Relationship launched in Viet Nam 15th September 2014. The campaign informed the users that a growing number of rhino horns where been infused with toxins.

The second campaign, Will Your Luck run Out? launched in early 2015 for the lead up to the Vietnamese New Year or ‘Tet’, also mentioned that radioactive tracers were being tested in rhino horns to try and reduce poaching.

While in South Africa in February 2015 to speak with representatives from both side of the rhino horn debate, it was apparent that pro-trade groups were worried about the horn infusion process, as it was physically devaluing horn from the consumers’ perspective. They were similarly concerned about the corresponding demand reduction campaign, psychologically devaluing horn from the consumers perspective. Undoubtedly this work could have undermined their trade legalisation plans. Campaign supporters in Viet Nam were telling us they were hearing that:

- Breaking The Brand is lying, horn infusion doesn’t work

- The poisons don’t spread through the horn

- The red poison forms into blobs and can easily by dug out of the horn

- Horn infusion is illegal and it has been banned in SA

As a result of the significant resources being used to undermine horn infusion, Breaking the Brand’s third campaign, What Does A Wildlife Criminal Look Like? focused on triggering status anxiety – that using rhino horn would diminish wealthy consumers status in the eyes of their peers. A slower process than the health anxiety strategy, but one the pro-trade groups couldn’t undermine.

So what is interesting, after losing more than a decade, radioactive tracers are again being put into rhino horn and people are again saying that this fact should be used to undermine consumption, with demand reduction campaigns in destination countries. Been there, done that and it works. By 2020, rhino poaching had fallen to 394, still sickeningly high but a significant dip from the 2014 peek of 1215. I hope this time around this work to physically devalue horn is supported and, most importantly, scaled.

What became very clear a decade ago when this was tested is that demand reduction cannot work while there is a desire to legalise the trade in rhino horn.

Conflicting Messages Create Inertia#

Pro-trade private rhino owners spent several years saying demand reduction campaigns didn’t work, so an international legal trade was the only option. The truth is that too many conservation organisations offered up the evidence for this by passing off awareness-raising and education campaigns as demand reduction and behaviour change. A lost opportunity to save rhinos.

The poaching of rhinos in South Africa has already started to increase again in recent years, rising to 500 in 2023. The population of white rhinos in Kruger National Park in South Africa is down to 2,000 rhinos, from over 8,000 in 2015. The vast majority of South Africa’s rhinos have been sold to private owners, in the name of ‘securing’ the population (as the government was unable to deal with the levels of poaching). Keeping rhinos is expensive and without the ability to sell horn, there is zero benefit in owning them. This was evidenced by the abysmal failure of trying to auction off John Hume’s rhinos last year before they were finally sold to African Parks.

Hence the relentless push by the rhino owners to get the government to further legalise domestic trade and come up with ways to circumvent the international trade ban. The strategy is always the same – get inquiries and panels set up that look at rhino poaching, and the costs associated with keeping them safe, conclude that it is unsustainable, and that legalising trade is the only way out of the dilemma. This goes hand-in-hand with endless academic articles written by ‘friendly’ researchers and with media stories floating models for trade legalisation and touting the supposed community benefits.

We fully agree that the costs of securing rhinos are huge in comparison to protecting other species or the needs of local communities. But legalising trade will not solve either problem. Community benefits are a smokescreen, only the owners stand to gain financially from legalising the horn trade. And, yes, I acknowledge that the SA government also has a stockpile.

The costs of protection will not go down either, legalising the trade will increase demand for horn as marketing in destination countries will suddenly be permitted and poaching will increase as a result. The total supply of horn from 20,000 white rhinos in the world will never be enough to satisfy the potential legal demand from SE Asia, particularly if it can be legally marketed and advertised.

Instead, what is needed is what we have been advocating for since 2018 – changing CITES to a model where businesses pay the cost of regulation of trade. We published a proposal on how to go about this in a manner that is feasible and equitable, where the businesses in the rich importing countries at the end of the supply chain pay the lion’s share of the regulatory costs. The appetite to make such a change is currently non-existent, so rhinos and many other species will stay on the merry-go-round of trying to ‘solve’ the poaching problem with the ‘solution’ that caused the problem in the first place. Under the free-trade mantra, the only acceptable solution to any trade problem is always more free trade – if it pays it stays!

Breaking News: Research Confirms Growing Old Gives You Wrinkles#

So back to the title of the article, why did I choose this?

- There are enough research papers confirming that there are no medical benefits of rhino horn, from a consumer, demand reduction, perspective; another isn’t needed.

- Ditto for anything that proves rhino horn is similar to fingernails.

- The history of advertising provides ample evidence of what makes people buy. We equally have ample evidence for demand reduction and behaviour change campaigns that work, especially around tobacco use and safety campaigns (driving, workplace safety etc.). We don’t need more research to know what drives behaviour change in people who are not intrinsically motivated to change.

I can honestly say in the years since, no matter what consumer group I look at, and for what species, there are only 3 motivations to stop them consuming the product:

- Health Anxiety: A perceived negative impact on the health of the user, or people they care about.

- Status Anxiety: A perceived negative impact on the status of the user, in the eyes of thier peers.

- If giving up the product lets them move into a higher status group, that they aspire to be a part of.

That’s it.

Any research that doesn’t genuinely add something new, particularly research repeating what has gone before and just reconfirming the same conclusions, is as useful as ‘Research Confirms Growing Old Gives You Wrinkles’. Rhinos deserve better than this, as do the other 1 million species at risk of extinction in the not-too-distant future.

Another 13 years of churning out research that doesn’t make any useful contribution to save one of the most iconic species, and simply maintains the inertia, contributes to collectively driving us towards biodiversity collapse.

For any groups that what more details on how to create and evaluate demand reduction campaigns, check out our Annual Reports and other documents here